THE WS SOCIETY ONLINE EXHIBITION 2024

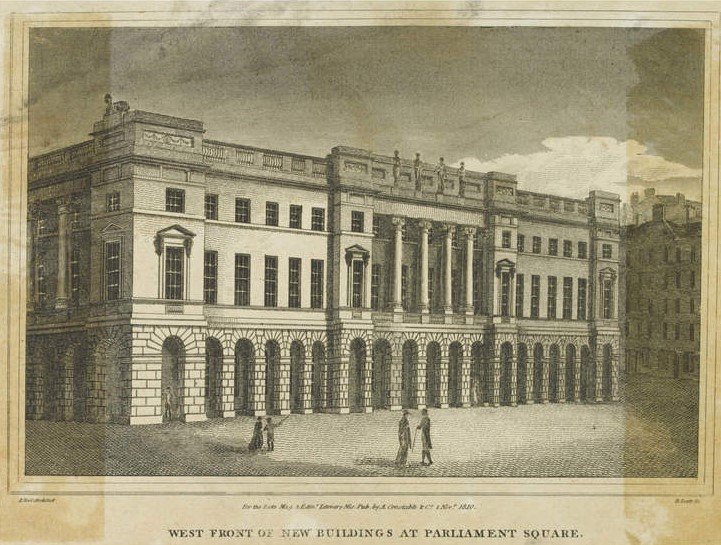

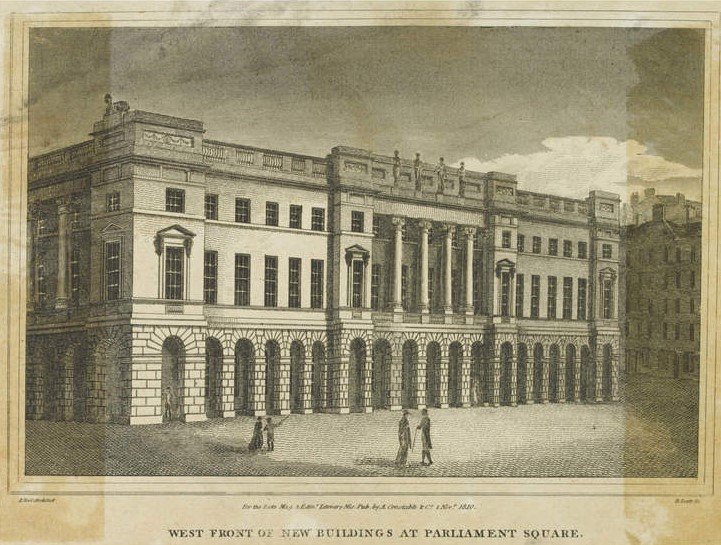

The first rumblings of the project that would become the Signet Library were heard in 1804, and the ground broken on what was then known as the “Library Block” in 1809 or 1810, with the project led by the builder of Heriot Row, Robert Reid. But by 1812, with the north front completed and the structure made watertight, it was clear that Reid’s concept was incapable of satisfying neither the WS Society’s needs and requirements nor those of the Faculty of Advocates. The project was running away from him: his clients were unhappy about light in the building, and their ambitions for it had changed in a way that Reid’s ideas were insufficient for. A new architect entered the scene: William Stark.

Stark had spent the early part of his career in the Russia of Catherine the Great, before returning to Scotland and making his career in Glasgow with buildings such as the courts at Saltmarket, St. George’s Tron Church and the original Hunterian Museum. His work in Glasgow had caught the eye of Sir Walter Scott, and he had been working on early designs for Abbotsford. Between early 1812, when he succeeded Robert Reid as the architectural lead on the project, and his early death the following year, Stark re-engineered the structure into the magnificent pair of library halls we see today.

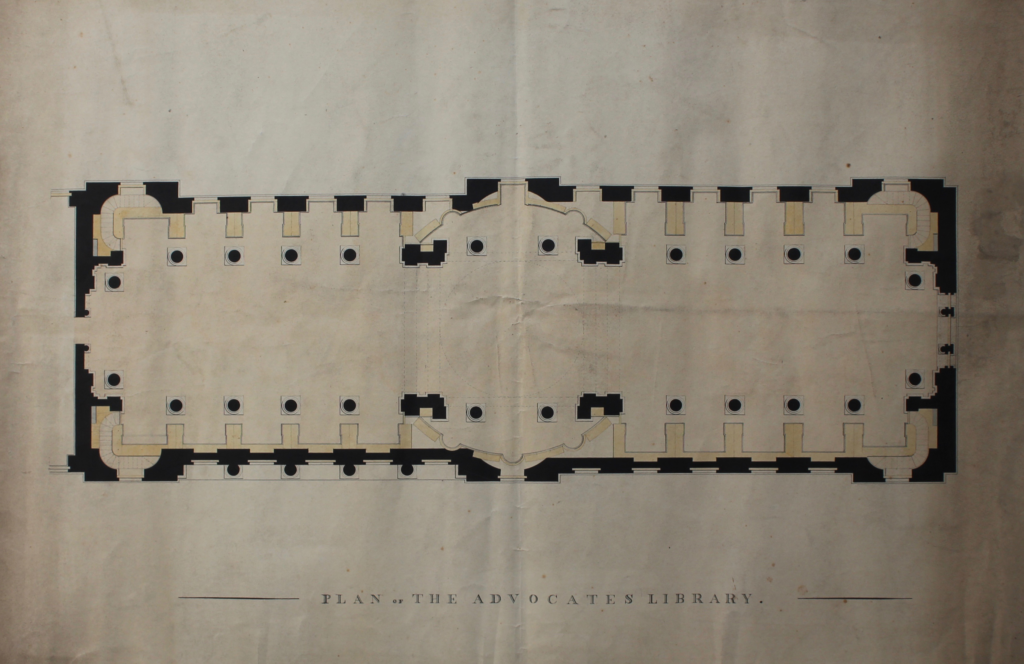

Only one of the drawings for William Stark’s Signet Library is known to survive. This, a floor plan of the Upper Hall was rediscovered at the Signet Library about ten years ago.

William Stark’s Signet Library is an architectural conversation between Scotland, St. Petersburg and the Italian architects Stark worked with in his youth. But Stark was not just the architect of the Signet Library’s magnificent buildings: he was the project’s saviour. His designs were not merely beautiful but were also the key to making the building work and function as the Writers and Advocates hoped and intended. They were solutions to the problems in the original design that had threatened the building’s very purpose.

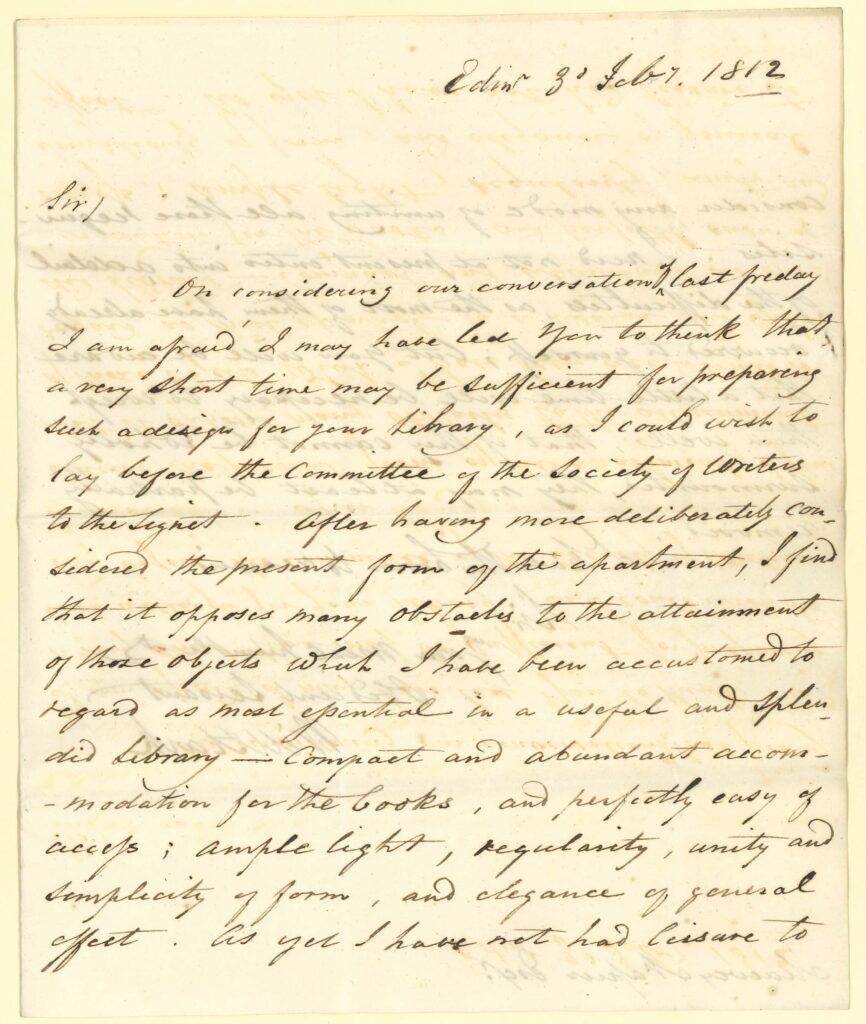

A vital part of that conversation is revealed in surviving 1812 correspondence between Stark and Macvey Napier. Robert Reid had had no concept of a library beyond that of a interior space that would later be “fitted up” with furniture and shelves by others, as occurred with Reid’s contemporaneous library and gallery at Paxton House. Stark’s first encounter with Reid’s Signet Library did not impress him:

After having more deliberately considered the present form of the apartment, I find that it opposes many obstacles to the attainment of those objects which I have been accustomed to regard as most essential in a useful and splendid library – compact and abundant accommodation for the books, and perfectly easy of acces; ample light, regularity, unity and simplicity of form, and elegance of general effect.

The biggest problem of all was the provision within the space of daylight. We gain some sense of the discussions between Stark and Napier on the question in Stark’s next surviving letter:

..I have discerned an excellent mode of lighting the Gallery without breaking out the openings formerly proposed, and have now no doubts remaining in regard to the expediency of the last projected arrangement, namely of picturing the north as well as the south windows, and of giving up the second tier on the south side, instead of which we can get ceiling lights for the gallery on both sides of the room, which will be handsome in themselves and will render it perfectly symmetrical.

Stark’s health, never strong, gave way not long afterwards, and his assistants working alongside Robert Reid, took the building to completion. The Writers to the Signet took over their part of the building in November 1815, with the Advocates following in 1821-22.

Remembering Stark in his Memorials, Sir Henry Cockburn gave an appreciation that contained a far grander and worthier one within it:

A few years before this William Stark, the best modern architect that Scotland had produced, appeared. After he had established his reputation at Glasgow and other places, bad health compelled him to seek a retreat in Edinburgh, where however he only survived till October 1813. Thus he was too young to have done much; but he had excited attention and given good principles, particularly in reference to the composition of towns. The magistrates consulted him on the best way of laying out the ground on the east side of Leith Walk; and he explained his views in a very sensible, though too short, memorial. On the 20th of October 1813 Scott mentions his death to Miss Baillie in these terms, “This brings me to the loss of poor Stark, with whom more genius has died than is left behind among the collected universality of Scottish architects.”

The reaction of visitors to Stark’s designs was immediate and emphatic. Writing in 1816, Isabella Spence said:

The Writer’s Library is a very large and truly magnificent room; finished with pillars, galleries, rich gilding, and all sorts of architectural ornaments, in a style that must astonish every stranger. At the same time, this astonishment is converted into admiration, on observing, that love of literature, which seems to be inherent in the Scotch character, displayed in such a splendid establishment; and that, erected solely at the expense of a body of men, who might be supposed too busy for the cultivation either of scientific or polite literature; and scarcely rich enough to erect such a costly repository for the treasures of learning. Their collection is said to be worthy of the receptacle in which it is deposited. (Elizabeth Isabella Spence, Letters from the North Highlands During the Summer 1816)

Further Reading

William Stark awaits his biographer. There is a typescript of George Thomson’s brief Memoir of William Stark, Architect in the National Library of Scotland, MS1758x.

Also see James Hamilton “Building ‘The Palace of Bokes’: Robert Reid, William Stark and the Signet Library” in The Book of the Old Edinburgh Club New Series Vol. 16 (2020)

For context, see A.J. Youngson The Making of Classical Edinburgh 1750-1840 (Edinburgh 1966; new edition Edinburgh 2019)

4. The Golden Age of the Signet Library

Macvey Napier: Golden Age Librarian