THE WS SOCIETY ONLINE EXHIBITION 2024

The Signet Library is the collection of the Society of Writers to HM Signet, a body of solicitors with origins at the medieval Scottish Court. The Library was founded in 1722, in the midst of a period of intellectual curiousity and growth. At the heart of this activity was the great Scottish historian and Writer to the Signet, James Anderson 1662- 1728, author of the Diplomata Scotia.

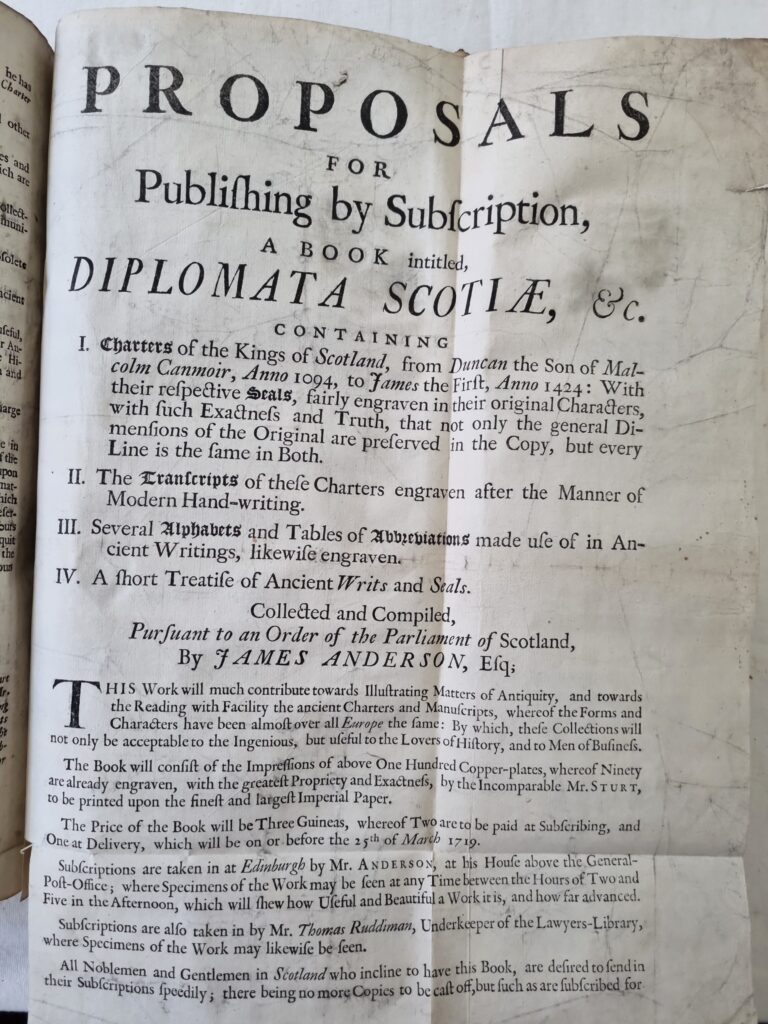

Anderson’s great work, the Diplomata Scotia revolutionised ideas on how ancient documents, charters and seals should be authenticated and interpreted. It might have been the culmination of a wide and brilliant career that ranged from reforming Scotland’s postal services to producing his landmark 1705 Historical Essay, Scotland’s first genuine example of modern archival scholarship. But promises of funding failed and he ended his life in poverty. The Diplomata Scotia would not be published until 1739, more than ten years after his death.

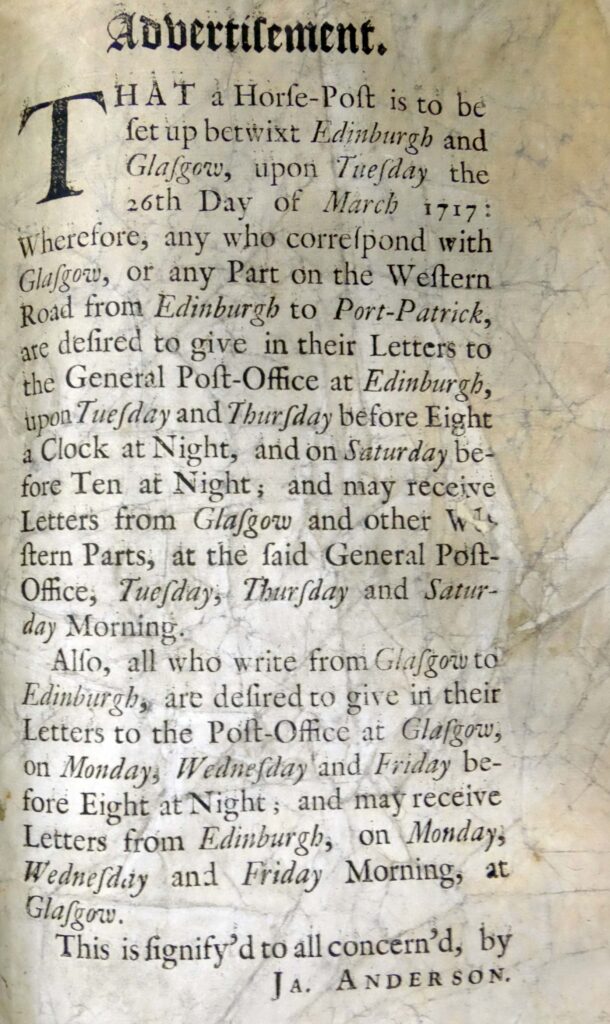

Writers to the Signet were Scotland’s principal conveyancers of land to the aristocracy and gentry in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and Anderson was not the first to find his professional contact with ancient documents turn into an all-consuming interest in history. Beginning in middle age with independent study in the library of Durham Cathedral, he took inspiration from the ideas of French historian Jean Mabillon about the appraisal of original records and the roles of paleography and diplomatic. In 1706 a tax was imposed on beer in Glasgow to fund his research but following the Union of 1707 no further state funding was forthcoming. A stint as Scotland’s Postmaster in the 1710s during which Anderson founded the horse post between Edinburgh and Glasgow provided some respite, but the fall from power of his Whig patrons brought with it his dismissal. He spent the rest of his life – and the rest of his fortune – in efforts to bring the culmination of his research to print in the form of the Diplomata Scotia, intended to be both a guide to Scotland’s ancient charters and a statement on the nature of historical research, but he died in London with the project all but completed yet unpublished. The project would be rescued by the great classicist and publisher Thomas Ruddiman and the Diplomata was eventually published in reduced but still magnificent form in 1737.

An anonymous Victorian writing in Notes and Queries commented

This is a very remarkable instance of the indifference manifested by the Scotish Members of Parliament to the honour and character of their nation. Here was an individual who had collected materials for the early history of his country – who had been led upon the ice by the Scotish Parliament before the Union – and by promises from the most influential of his countrymen, before the good things of London had rendered them selfish – utterly neglected, excepting by a few of his compatriots, and left to penury and want – having previously sacrificed a lucrative and respectable profession, in which he would indubitably have realised a large fortune, to preserve the early records of his native land. England, with all her wealth, never gave forth a volume so intrinsically valuable, and so beautifully executed, as the Diplomata Scotia: nevertheless, in place of wealth, it brought poverty to the hearth of the ill-fated Anderson. NQ 2nd series no. 5 p. 473

The Portrait of James Anderson

The WS Society’s fine portrait of James Anderson shows him as a proud antiquary, working in the company of the charters and books that occupied him for the bulk of his adult life. Now hung in the Commissioners Room, it has been in the Society’s possession since it was acquired for £10 in March 1850, since which time it has been attributed to John Vanderbank c.1694-1739.

But it is unlikely to be Vanderbank’s work. The earliest account of the portrait’s commission, that of George Lockhart of Carnwath, was published in 1714, when Vanderbank was only 20 and ten years away from the establishment of his London studio. Furthermore, the earliest period of Vanderbank’s success coincided with James Anderson’s deepest late-life poverty when he was struggling to complete his life’s work in the face of hostile creditors and in no position to commission a portrait as fine as that we see today.

The portrait’s style is closely comparable with work emanating from the busy studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller in the years c. 1708-1715, when Kneller was preeminent in London. This was also the period during which Anderson, denied promised funding from Parliament, was engaged in fruitless efforts to secure patronage from the most powerful politician of the age, Robert Harley. George Lockhart viewed Anderson as an epitome of the kind of talented petitioner Lord Harley was most apt to disappoint:

Ther was one Mr. James Anderson a Scots gentleman of very great merit, who had done his native country great service by a book asserting the independence of the crown and kingdom of Scotland, wrot in a good style and with great judgement and learning. This gentleman, by his application to the study of antiquityes, having neglected his other affairs and having, in search after antient records, come to London, allmost all the Scots nobility and gentry of note recommended him as a person that highlie deserved to have some beneficiall post bestowd upon him; nay the Queen herself (to whom he had been introduced and who took great pleasure in viewing the fine sealls and charters of the antient records he had collected) told my Lord Oxford she desird something might be done for him; to all which His Lordship’s usuall answer was, that ther was no need of pressing him to take care of that gentleman, for he was thee man he designd, out of regard to his great knowlege, to distinguish in a particular manner. Mr. Anderson being thus putt off from time to time for fourteen or fifteen months, His Lordship at length told him that no doubt he had heard that in his fine library he had a collection of the pictures of the learned both antient and modern, and as he knew none who better deserved a place ther than Mr. Anderson, he desired the favour of his picture. As Mr. Anderson took this for a high mark of the Treasurer’s esteem and a sure presage of his future favours, away he went and got his picture drawn by one of the best hands in London, which being presented, was graciouslie received (and perhaps got its place in the library) but nothing ever more appeard of His Lordships favour to this gentleman, who having thus hung on and depended for a long time, at length gave himself no furder trouble in trusting to or expecting any favour from him; from whence, when any one was askd, what place such or such a person was to get, the common reply was, A place in the Treasurer’s library..

George Lockhart of Carnwath, Memoirs and Commentaries Upon the Affairs of Scotland from 1702 to 1715 in The Lockhart Papers edited Antony Aufrere (London: published for William Anderson, 1817) Vol. 1 p. 371

Anderson may have been happy enough with his portrait to have it copied. A letter to Anderson by the young Scottish artist John Alexander (1686-1766) dated 12 September 1710, when Alexander was briefly working in London, discusses a copy Alexander was engaged in making for Anderson of a portrait of Mary Queen of Scots. Alexander’s letter also mentions “your picture” which he has left with Anderson’s sister Mary. Alexander would leave soon after for an apprenticeship in Italy, where he would make his artistic fortune painting members of the Jacobite exile community.

Alexander’s letter is transcribed in Notes and Queries Series 2 no. 5 p.272 1858 (i.e. almost a decade after the acquisition of Anderson’s portrait by the WS). The transcriber remarks: “..curious in showing there did exist a portrait of Anderson. What has become of it is not known; and it is much to be regretted that there is no engraving of a man who did so much for the history of Scotland.” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography of 2004 echoes this and reflects on a “lost” portrait: the WS Society is in correspondence with them to add the portrait to the Dictionary’s biography of Anderson.

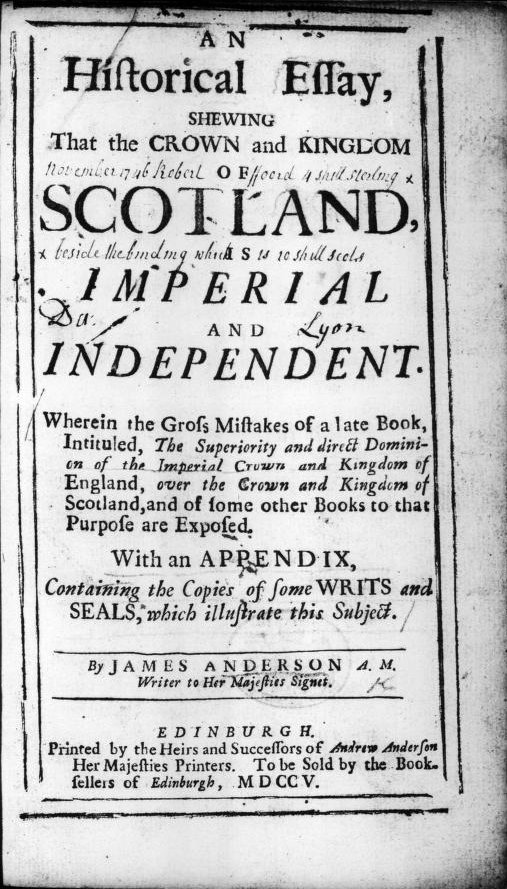

James Anderson’s “Historical Essay” of 1705

An historical essay, shewing that the crown and kingdom of Scotland, is imperial and independent.

James Anderson WS (1662-1728), lawyer, postmaster and historian

Edinburgh : printed by the heirs and successors of Andrew Anderson. To be sold by the booksellers of Edinburgh, 1705

This polemical work was Anderson’s first and took the form of an angry response to a pamphlet by the Englishman William Atwood, The Scotch Patriot Unmask’d, which deployed Anderson’s own 1703 research into charters held at Durham Cathedral to reiterate medieval English claims to the throne of Scotland. But although Anderson was writing as part of a propaganda war, his Historical Essay was novel and valuable in that it incorporated approaches to history – such as a critical approach to historical records and the use of paleography – that had been pioneered in France by Jean Mabillon and which would shape the remainder of Anderson’s intellectual life.

The subject of Anderson’s dispute with Atwood – whether the Scottish throne owed homage to that of England or was “imperial”, independent – was not a new one. It had been rumbling since the sixteenth century at the very latest – Sir Thomas Craig’s manuscript contribution, Scotland’s soveraignty asserted. : Being a dispute concerning homage, against those who maintain that Scotland is a feu, or fee-liege of England, and that therefore the King of Scots owes homage to the King of England. was translated and published by George Ridpath in London in 1695.

The question of homage was a vital one to Scottish national consciousness: so was the idea of Scotland’s Ancient Monarchy (in which Scotland’s royal line extended unbroken into pre-Roman times), and the concept of Scotland being an unconquered nation (seeing off both the Romans and Edward I). Anderson would find his friend Sir Robert Sibbald at his elbow contributing to the homage debate; his friend Thomas Innes would deal a fatal blow to the idea of the Ancient Monarchy, and his friend Alexander Gordon would take issue with Sibbald over how much of Scotland’s resistance to Roman domination was a matter of national virility or merely the outcome of fluke and circumstance.

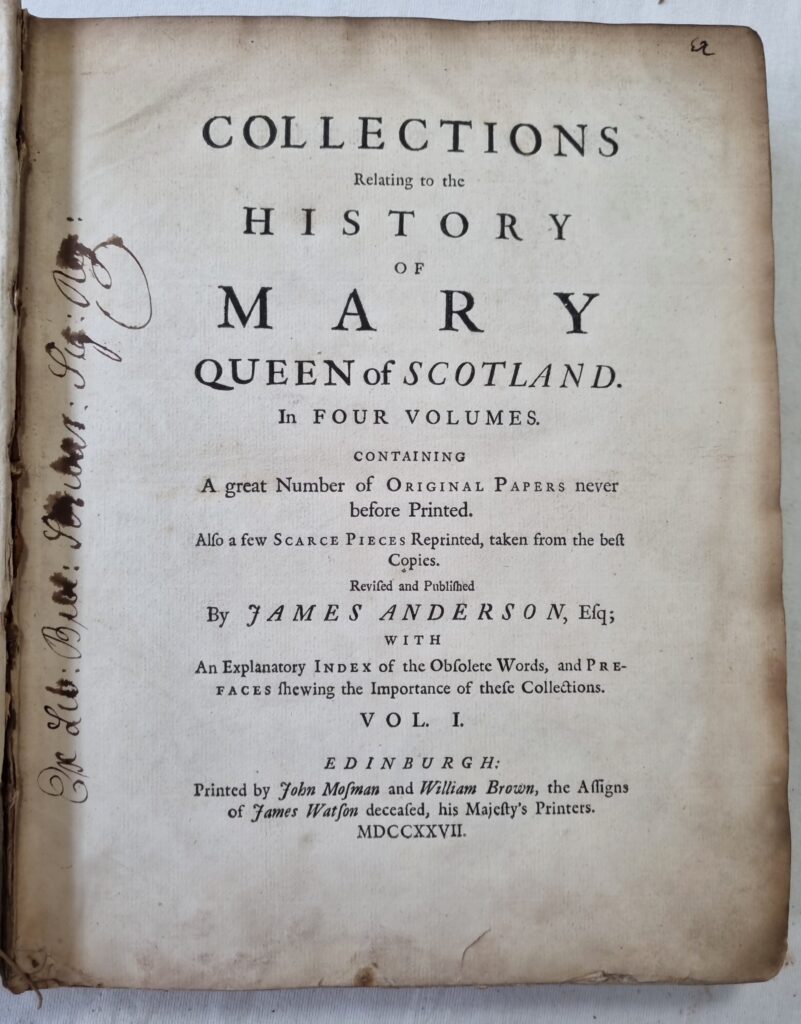

James Anderson’s “Collections Relating to the History of Mary Queen of Scotland” of 1727-28

Collections relating to the history of Mary Queen of Scotland. In four volumes. Containing a great number of original papers never before printed. Also a few scarce pieces reprinted, … Revised and published by James Anderson, Esq; with an explanatory index of the obsolete words, and prefaces shewing the importance of these collections.

James Anderson WS (1662-1728), lawyer, postmaster and historian

Edinburgh: printed by John Mosman and William Brown, the assigns of James Watson deceased [and Thomas Ruddiman], 1727-28.

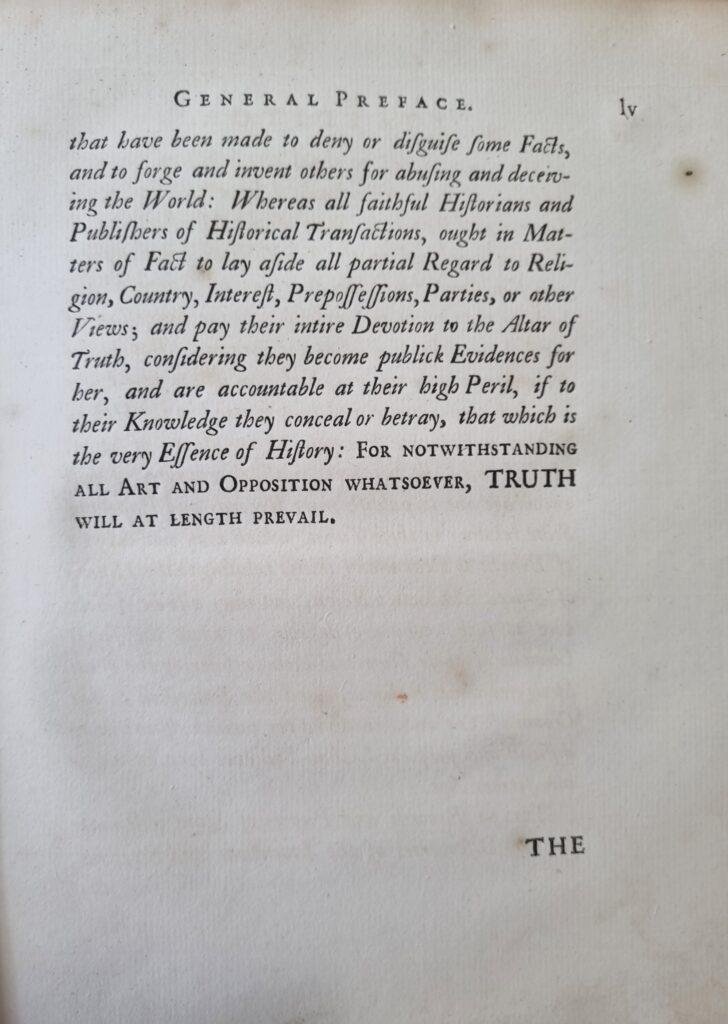

Anderson’s last work: four volumes of original documents and anti-Marian Jacobite polemic. His General Preface to the work concludes thus:

Whereas all faithful historians and publishers of historical translations, ought in matters of fact to lay aside all partial regard to religion, country, interest, prepossessions, parties, or other views; and pay their entire devotion to the altar of truth, considering that they become publick evidences for her, and are accountable at their high peril, if to their knowledge they conceal or betray, that which is the very essence of history: FOR NOTWITHSTANDING ALL ART AND OPPOSITION WHATSOVER, TRUTH WILL AT LENGTH PREVAIL.

The work was published by Anderson’s son Patrick shortly after his death in early 1728. It had been long awaited: the great historian of the Scottish Reformation, Robert Wodrow, wrote to James Frazer:

Please to give my dearest respects to Mr. Anderson, and my best wishes to the useful work he is upon, and, if I might add it, my complaint of his unkindness in not favouring me with a letter, when I have writen twice or thrice to him. I know his hurry of bussines and labour, and I had almost said his lazines to write, but I’le be extremely fond to hear from, and tho’ he should forget me, I’le neuer forget him. We are very impatient here, that his collections about Queen Mary, the good regent, & our reformers are not published, and exceedingly long for them. I expect many valuable things in them, and hope for some light from them for the lives of the Reformers. [Robert Wodrow to James Frazer, Nov 18 1726 Analecta (ed. James Maidment) p. 317]

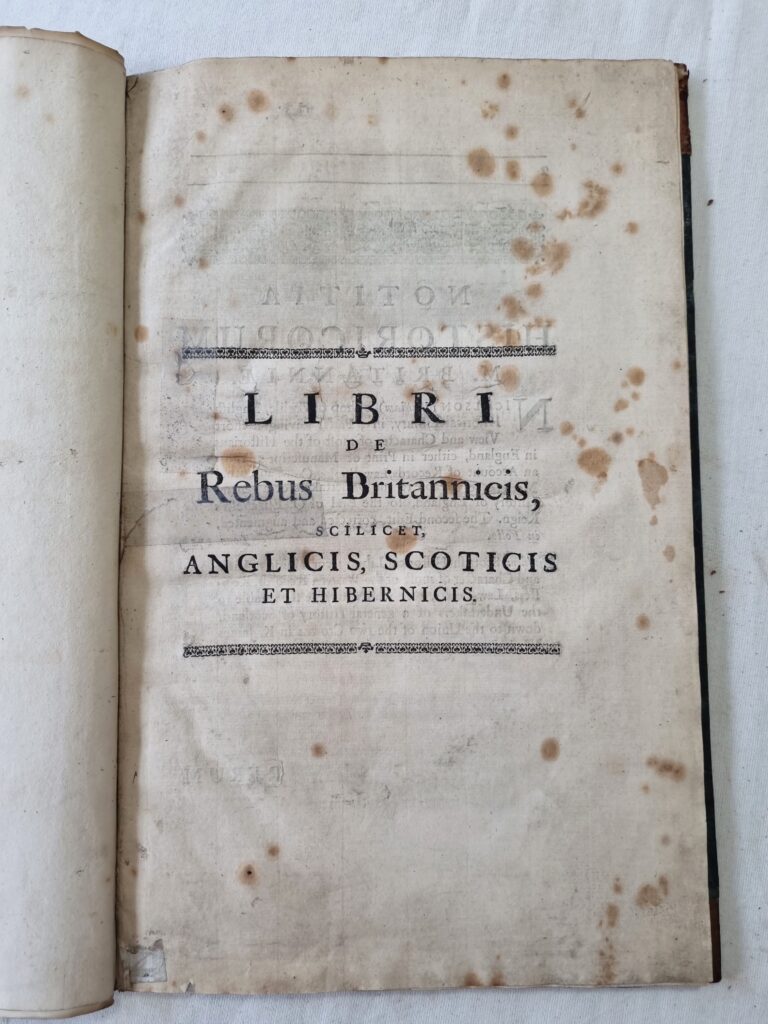

James Anderson’s Libri de rebus Britannicis c. 1726

Libri de Rebus Britannicis, scilicet Anglicis, Scoticis et Hibernicis.

[A bibliography]

James Anderson WS (1662-1728), lawyer, postmaster and historian

[Edinburgh?], [ca. 1725]

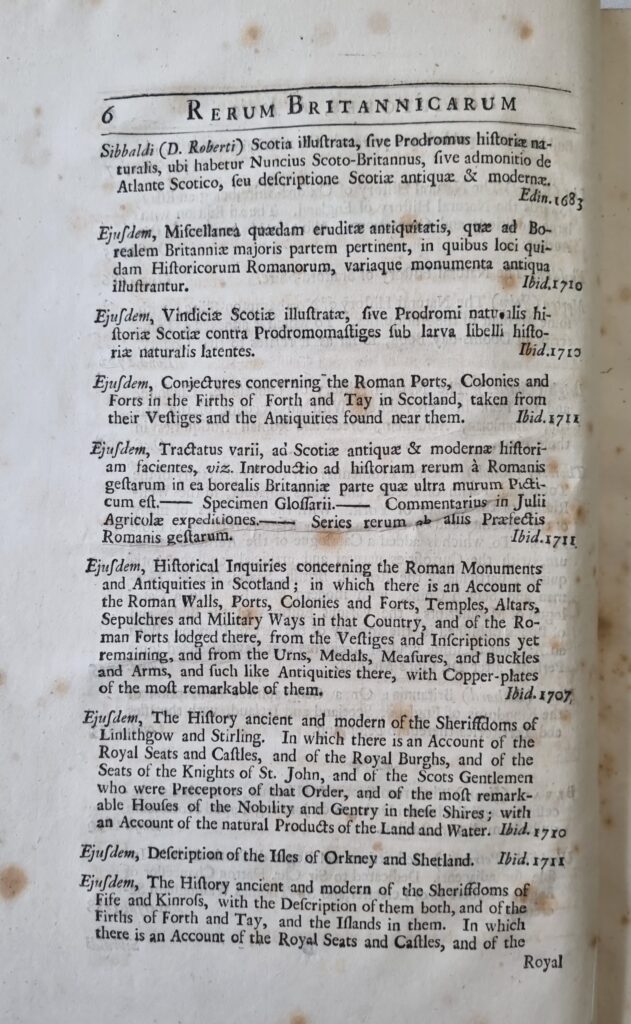

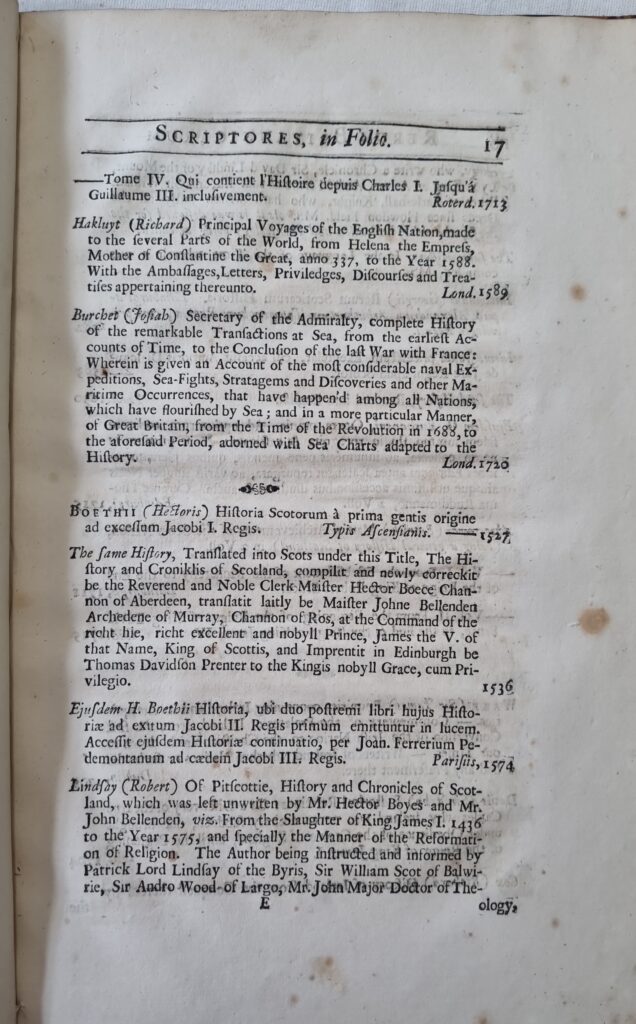

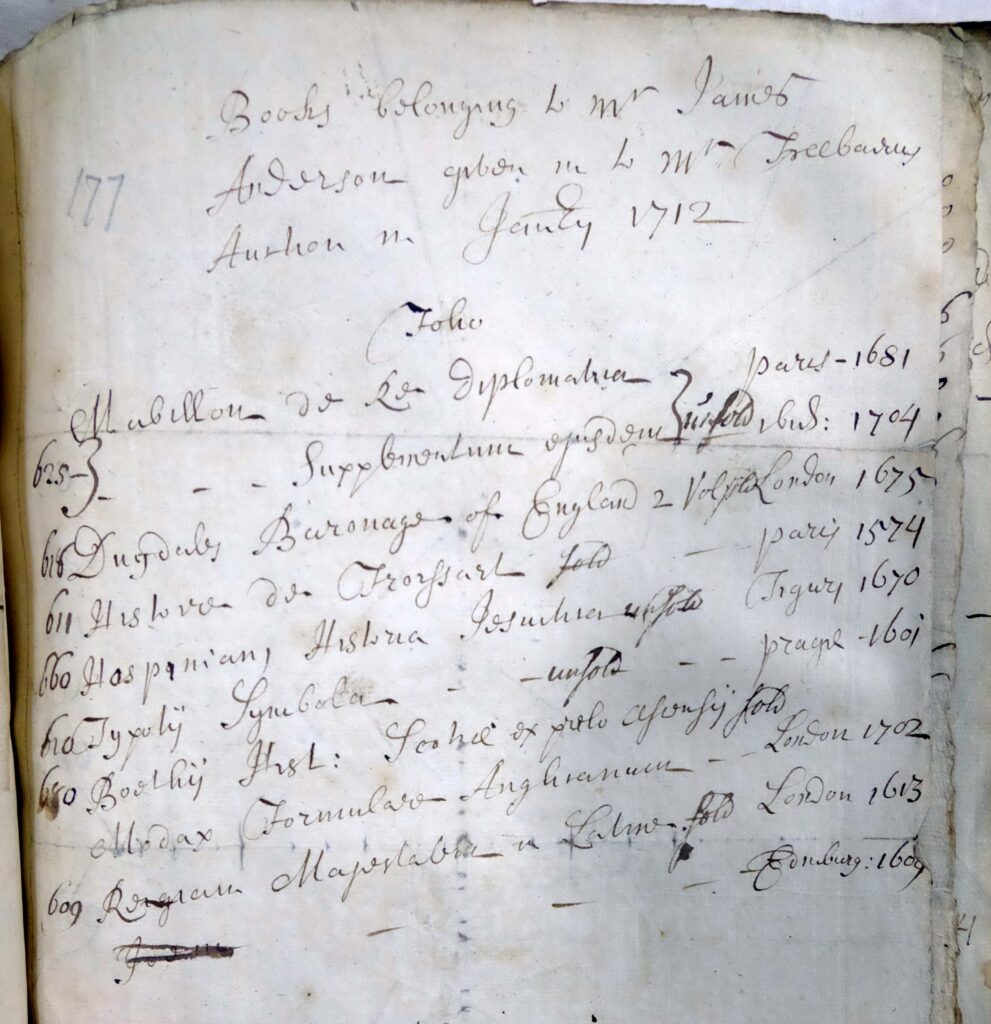

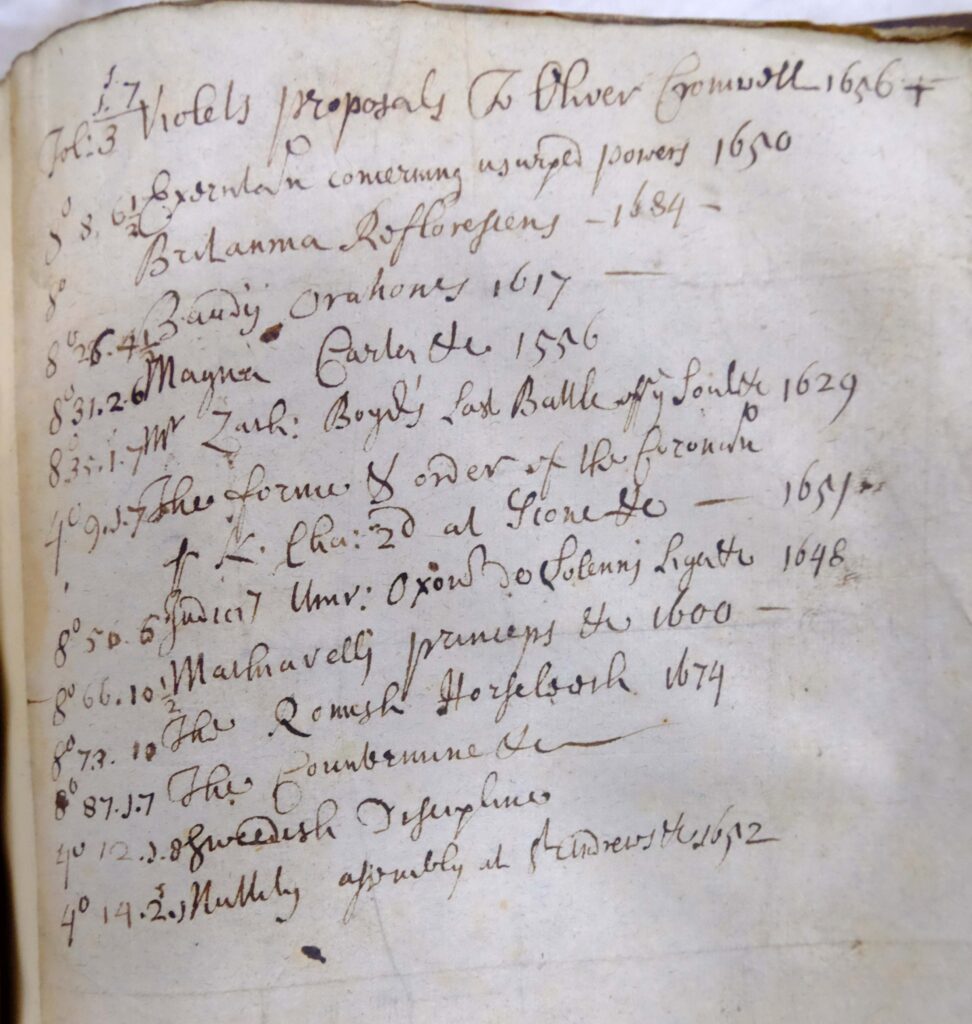

By the early 1720s, Anderson’s efforts to secure the publication of the Diplomata Scotia had lost him his profession and much of his wealth. This bibliography is believed to be a catalogue of Anderson’s exceptional library, or at least that part of it devoted to history and public affairs, assembled as part of a failed attempt to sell the collection to King George I. The collection was splendid enough to extract a mea culpa from Anderson, in his letter to his friend the Irish dramatist Sir Richard Steele (1672-1729):

..being a private man, and having a numerous family, I may be justly reproached for such a large and expensive collection. But I had occasion for many of them, and the more complete my collection was, more especially of British matters, and of the history of learning and dictionaries, I imagined they would turn to the better account to me or mine..I am fully persuaded, though I had no interest in the matter, that his Majesty could not doe a thing more obliging and beneficial to this country [than purchasing Anderson’s Library]. By the small knowledge I have of these matters, I may adventure to say, that the more the history of Britain is known, the brighter will the present constitution appear, and less dispute amongst our divines; and how much the study of these matters by noblemen and gentlemen might be of service to their prince and country is obvious, which the founding of a royal historical library might much contribute to”.

Feb 16 1720/1721. Analecta (ed. James Maidment) p.19]

The catalogue is so much more than the list of one man’s collection, however. It is a marvellous tour and summary of Scottish and British historical writing and thinking: a majestic survey of the study, science and craft as it stood on the threshold of the Enlightenment. Miserable though the context of its creation was, the catalogue is itself a thing of beauty and dignity, worthy of a high place amongst Anderson’s works.

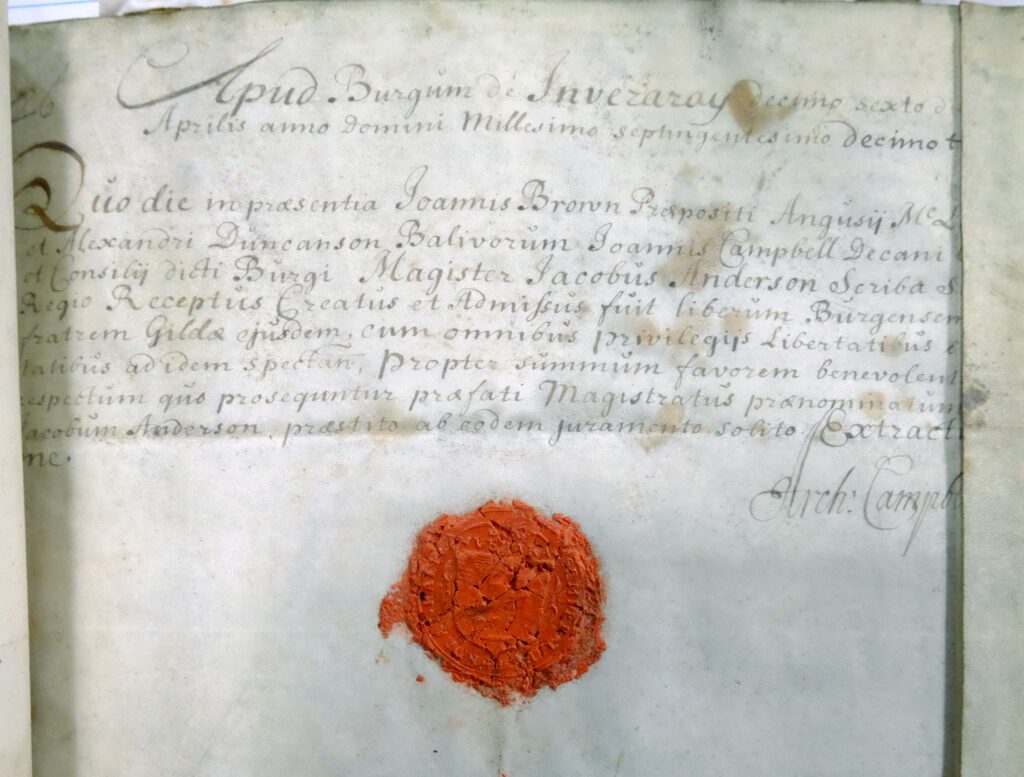

James Anderson’s Personal Papers

Collected Papers of James Anderson (Signet MS 58 & 59)

James Anderson WS (1662-1728), lawyer, postmaster and historian

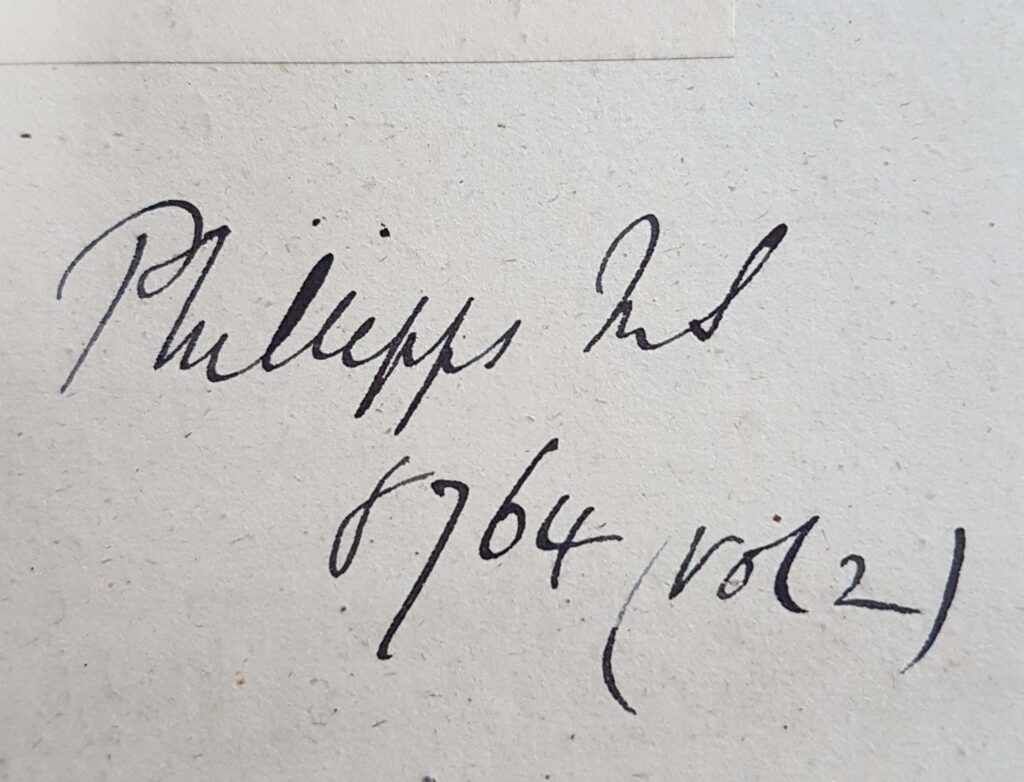

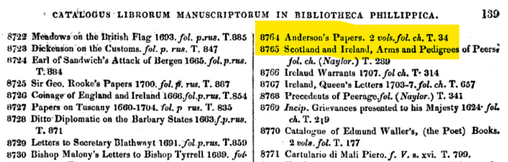

This pair of volumes is one part of a far greater collection of the personal papers of the Writer to the Signet and historian James Anderson. They were acquired from one of the many sales dispersing the vast manuscript collection of the Victorian eccentric Sir Thomas Phillipps, whose catalogue number (and characteristic binding) remain.

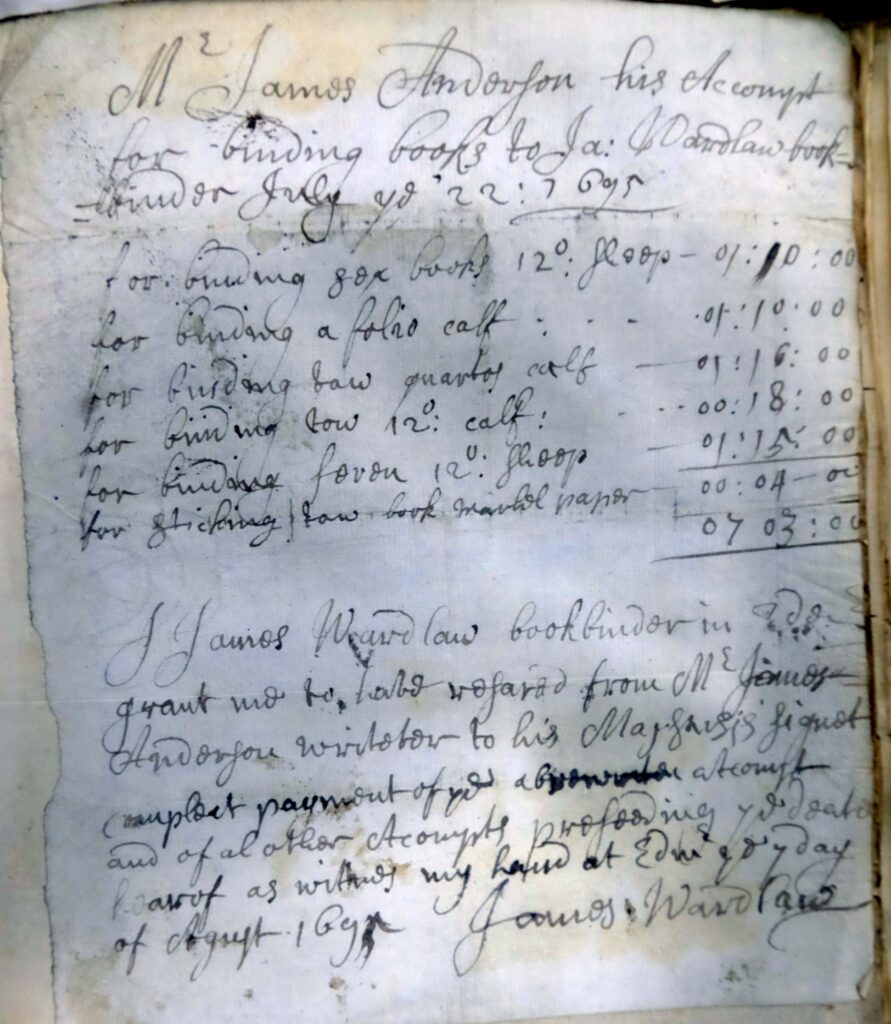

Anderson’s papers cover his time as Scotland’s Postmaster, and include much personal correspondence besides, with fascinating insights into the life of a well-off middle class Scot of the seventeenth century.

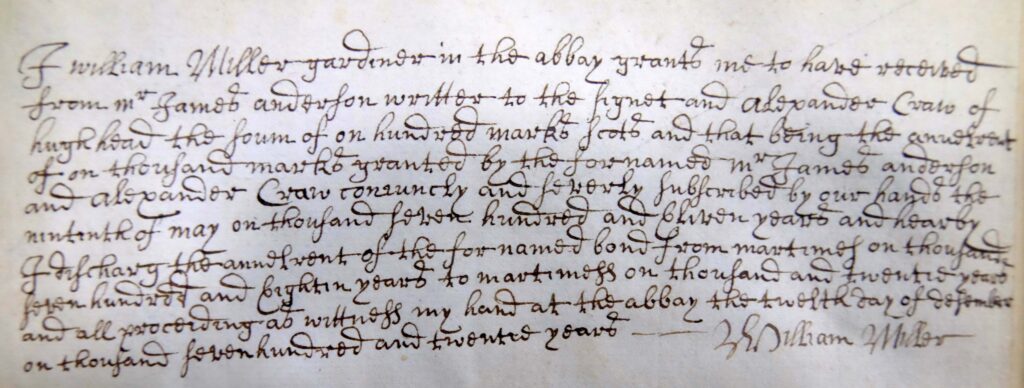

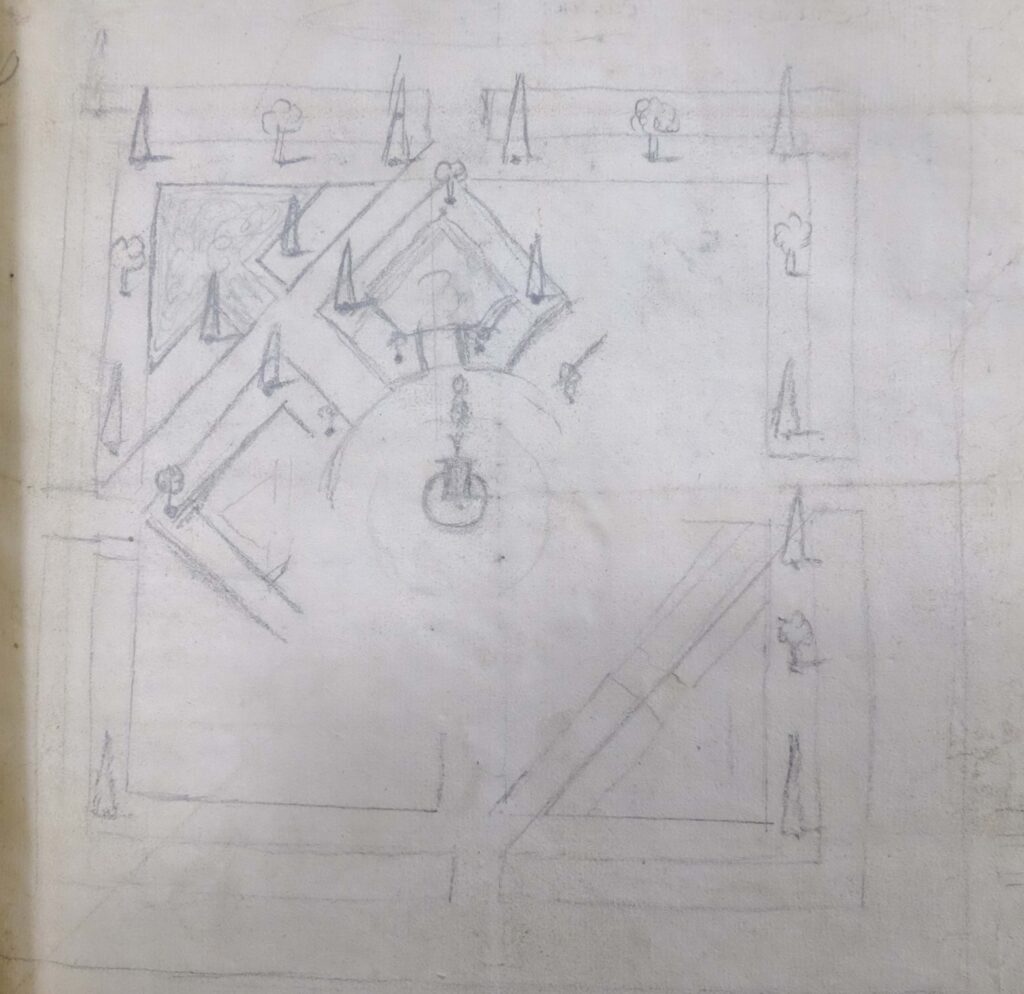

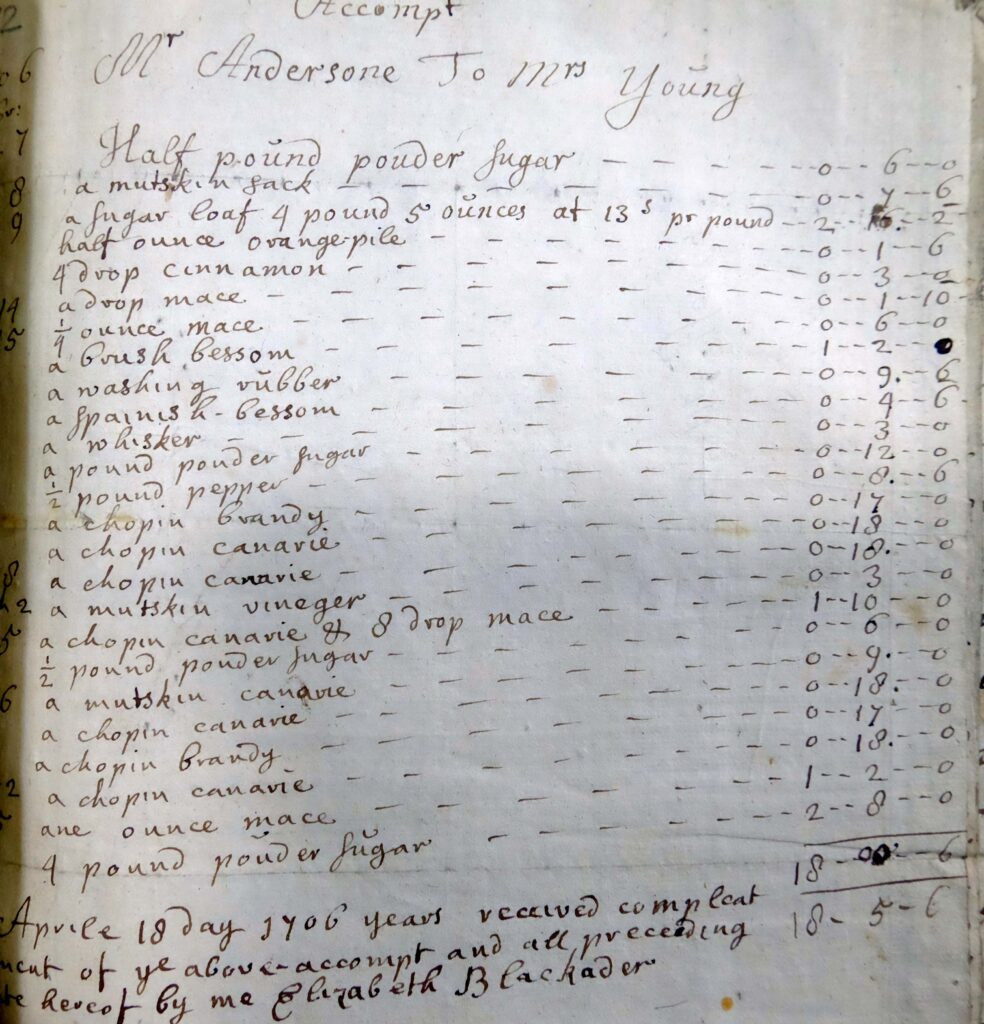

Included is a garden plan and a letter from the royal gardener William Miller, one of Edinburgh’s first Quakers and the father of a horticultural dynasty. There are even some of Anderson’s shopping bills.

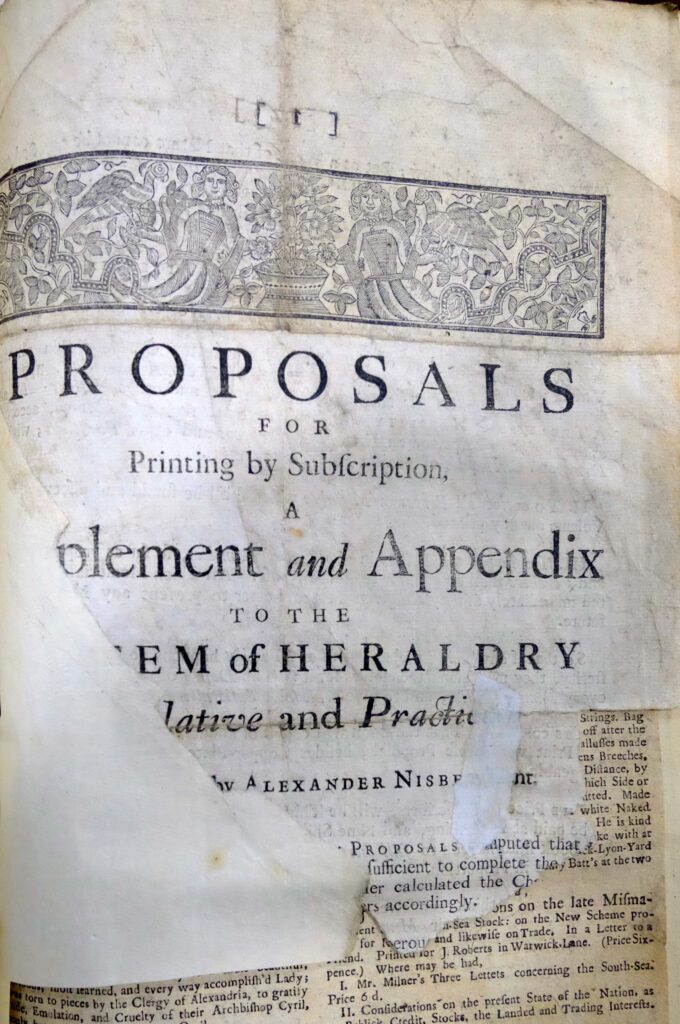

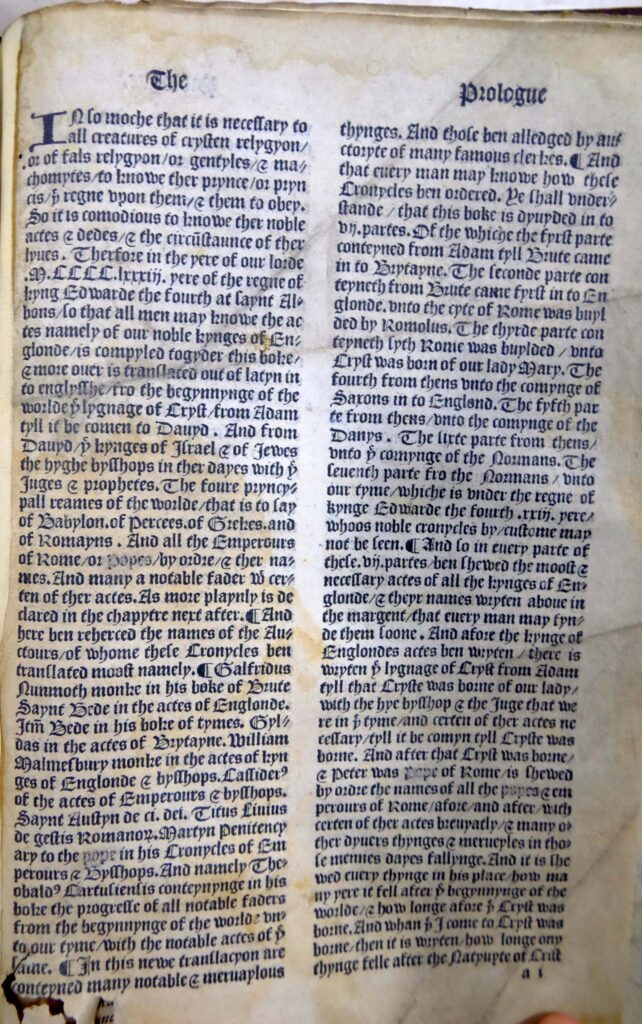

Anderson was a bibliophile and his papers contain proposals for Scottish Enlightenment publications such as Nisbet’s Heraldry – and also fragments of books, such as a page from Julian Notary’s 1515 St Alban’s Chronicle.

Some of Anderson’s own book lists are here, which register the presence in his library of Jean Mabillon’s De Re Diplomatica, the inspiration for his own Diplomata Scotia.

Additional collections of Anderson papers are held by the National Library of Scotland (Adv.MS.29.1.2), the Library of the University of Edinburgh (La ii 101) and the National Records of Scotland (GD224/1058 and GD18/5020).

A James Anderson Chronology

Born 5 Aug 1662 son of Patrick Anderson, presbyterian minister of Walton, Lanarkshire, imprisoned on the Bass during the Restoration – Signet has MS relating to him which should be included here.

Edinburgh University 1677-1689, MA. Apprenticed to Robert Richardson WS, admitted WS 6 June 1691. Early clients – Duke and Duchess of Argyll and their son the second Duke. Friends with Sir Robert Sibbald, Sir James Dalrymple, Captain John Slezer.

1703 trip to Durham to view records – transfer of his interest from legal practice to history begins around this time.

Involved in controversy over succession to Queen Anne – was the English 1701 Act of Settlement also binding on Scotland, who’d passed no such Act? 1704: William Atwood cites Anderson’s Durham research as proof that Scotland was subject to the English crown. 1705 Historical Essay is written in response – influence of Mabillon, new approaches to critical assessment of historical records via paleography, diplomatic (the study of ancient manuscripts). Enthusiastic reception, 1705 Scottish parliament grants £4800 Scots for further research.

Embarks on Diplomata Scotia. 1706 grant of £3600 Scots from impostion on ale in Glasgow. 1707 reported progress to committee – had spent a further £590 of his own money. Agreed he was to be paid this back plus £1050 Sterling, but this payment a victim of the Union of Parliament.

Moves to London at around this time.

According to George Lockhart of Carnwarth, Commentaries vol. 1 p. 371, his appeal to Harley for help unsuccessful but Harley flattered him into having his portrait made at his own expense to be hung in Harley’s library. Portrait painted 1710 (Notes and Queries 2nd Series 5.272) but “disappeared.” Victorian attribution to John Vanderbank likely to be incorrect and portrait instead the work of the studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller.

Becomes deputy postmaster-general for Scotland June 1715 after fall of Harley through his connection with Duke of Argyll, introducing horse posts between Edinburgh and Glasgow and Edinburgh and Stirling. Returns to Edinburgh. But dismissed in 1717 after fall of Argyll and returns to London.

Continues on Diplomata in poverty.

1718 attempts to raise funds via subscription but insufficient interest.

1721 attempt to sell his library to King George I via his friend Sir Richard Steele.

1723 memorial to government asking for promised money but no result.

1727-1728 publishes Collections Relating to the History of Mary, Queen of Scotland. Anderson a Whig Presbyterian but this collection of documents and polemic fair to his opponents.

Pledges the plates of the Diplomata to friend the bookseller Thomas Paterson.

Dies of apoplexy 3 April 1728; creditors seize his possessions.

Paterson suggests 1737 publication to Ruddiman – Diplomata appears with Latin into by Ruddiman in 1739 which is subsequently translated and published separately.

Further Reading

Kelsey Jackson Williams – The First Scottish Enlightenment: Rebels, Priests and History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

William Ferguson – “James Anderson’s Historical Essay on the Crown of Scotland [Introduction]” in Stair Society Miscellany III (Edinburgh: The Stair Society, 1992)

Alexander du Toit, “James Anderson (1662-1728), historiographer and antiquary” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004)

Thompson Cooper, “James Anderson” in Dictionary of National Biography vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1885)

- Setting The Scene : Lawyers and Intellectuals Before 1722