THE WS SOCIETY ONLINE EXHIBITION 2024

The Signet Library’s birth took place during the first concerted period of Scottish legal publishing and shared historical roots with it. The decades following the Restoration of the Monarchy had been ones of instability for the WS Society, with constant changes of leadership and accusations of falling standards and even corruption. But that instability had followed on from one of the greatest shocks in the long history of the Scottish legal system, one that fed into a nascent Scottish legal publishing scene.

Immediately following the execution of King Charles I in 1649, the Scottish Estates had declared his son Charles II as King, prompting Oliver Cromwell and the New Model Army to invade Scotland. After two brief but entirely decisive battles, Scotland was subjugated. Among Cromwell’s first acts in power was to abolish the century-old College of Justice in Scotland, replacing it over the lifetime of the Interregnum with a commission, more than half of which consisted of English judges. The Court of Session would return with the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, but the threat to the independence of Scots Law had been deeply alarming to Scottish legal intellectuals.

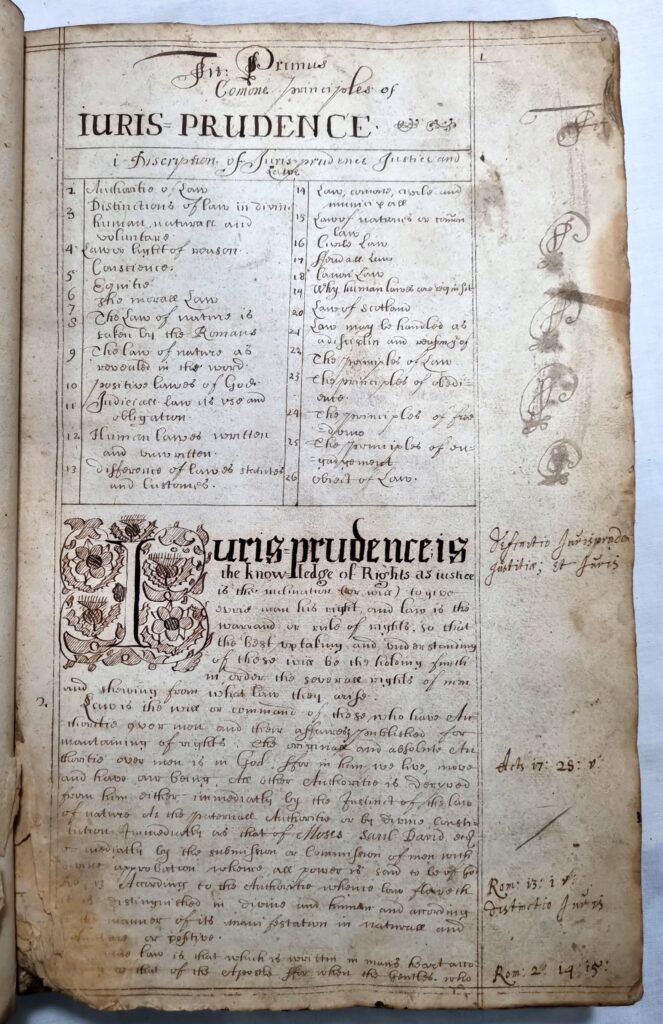

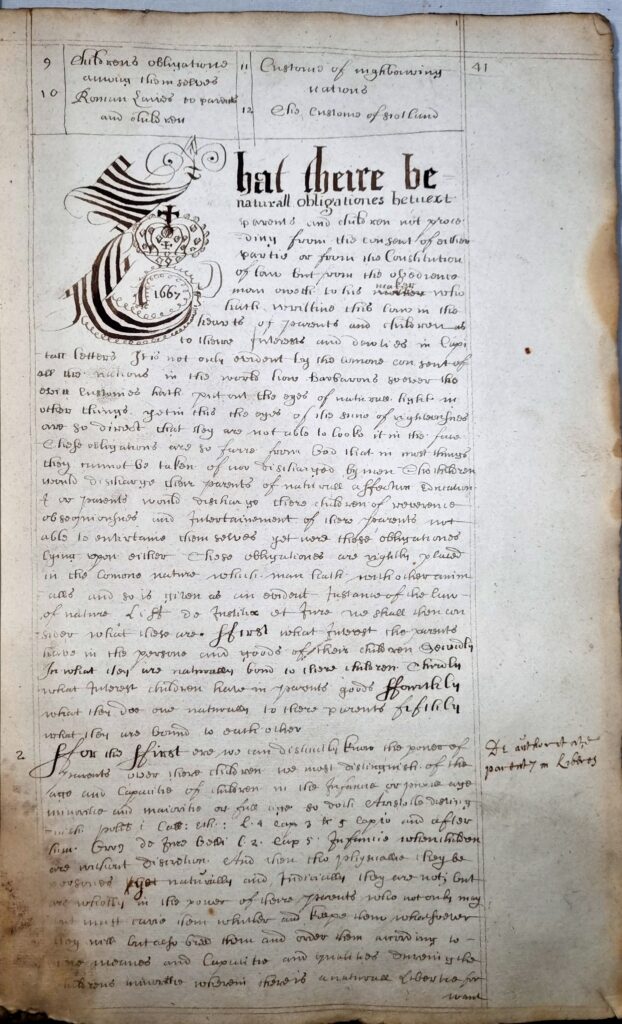

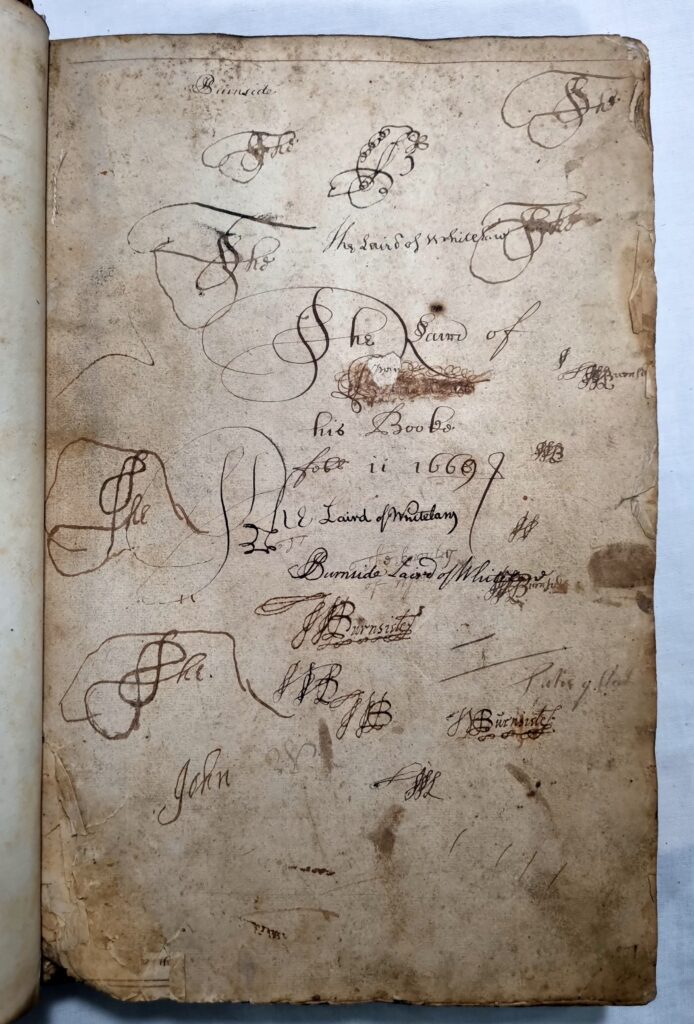

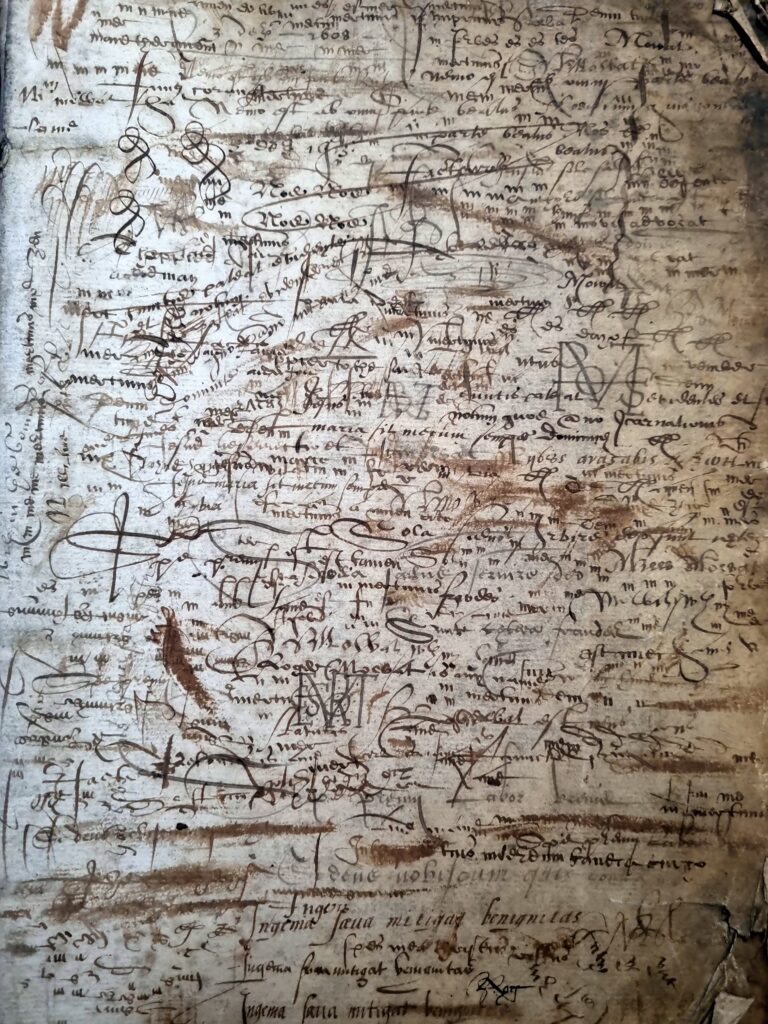

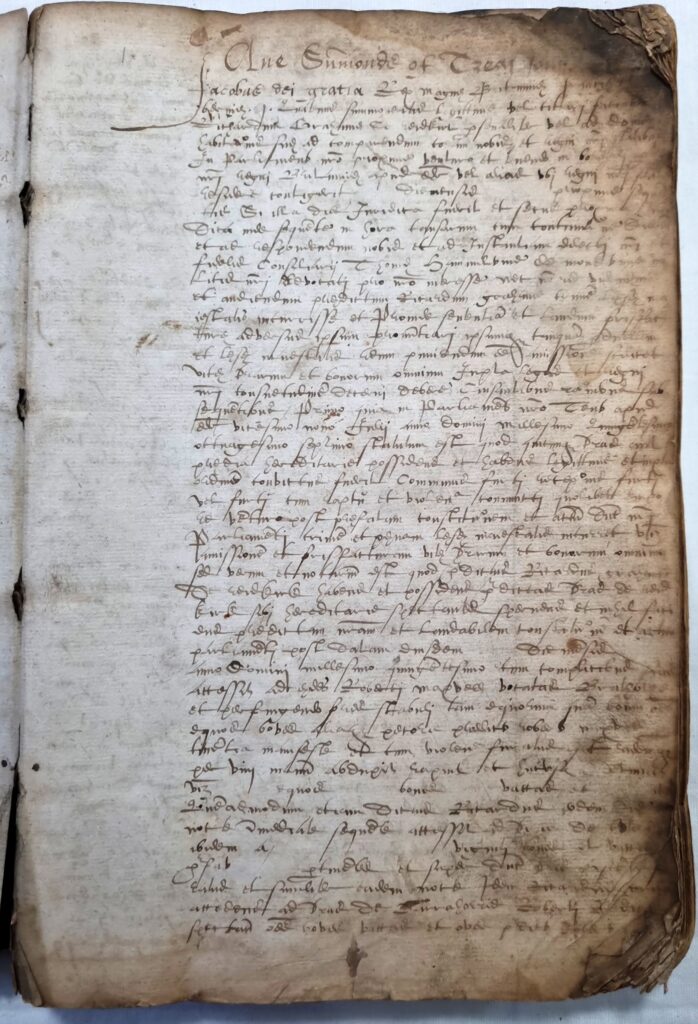

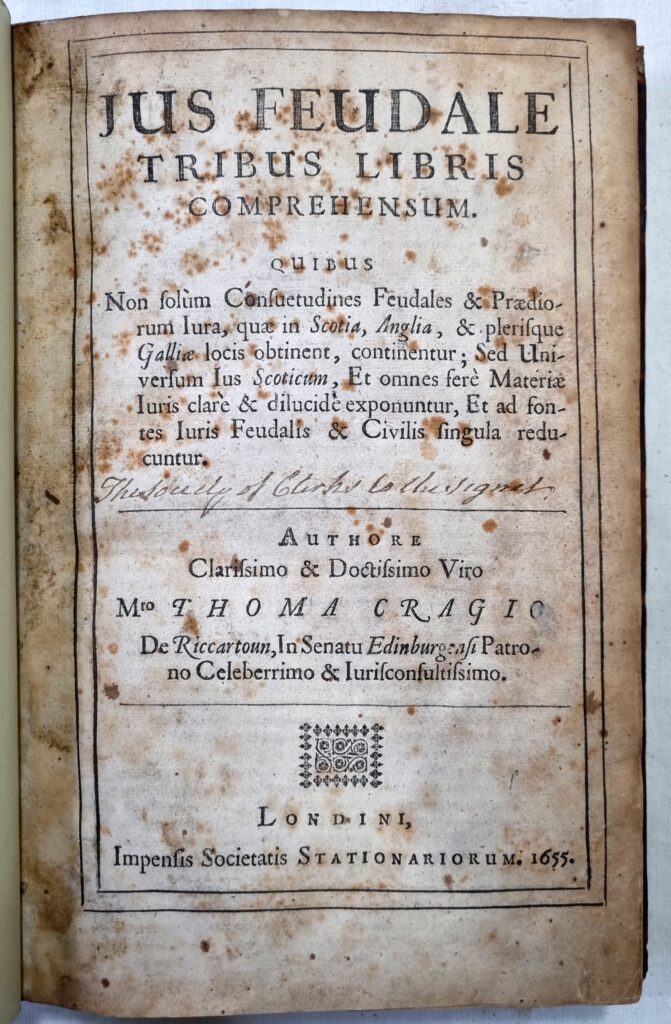

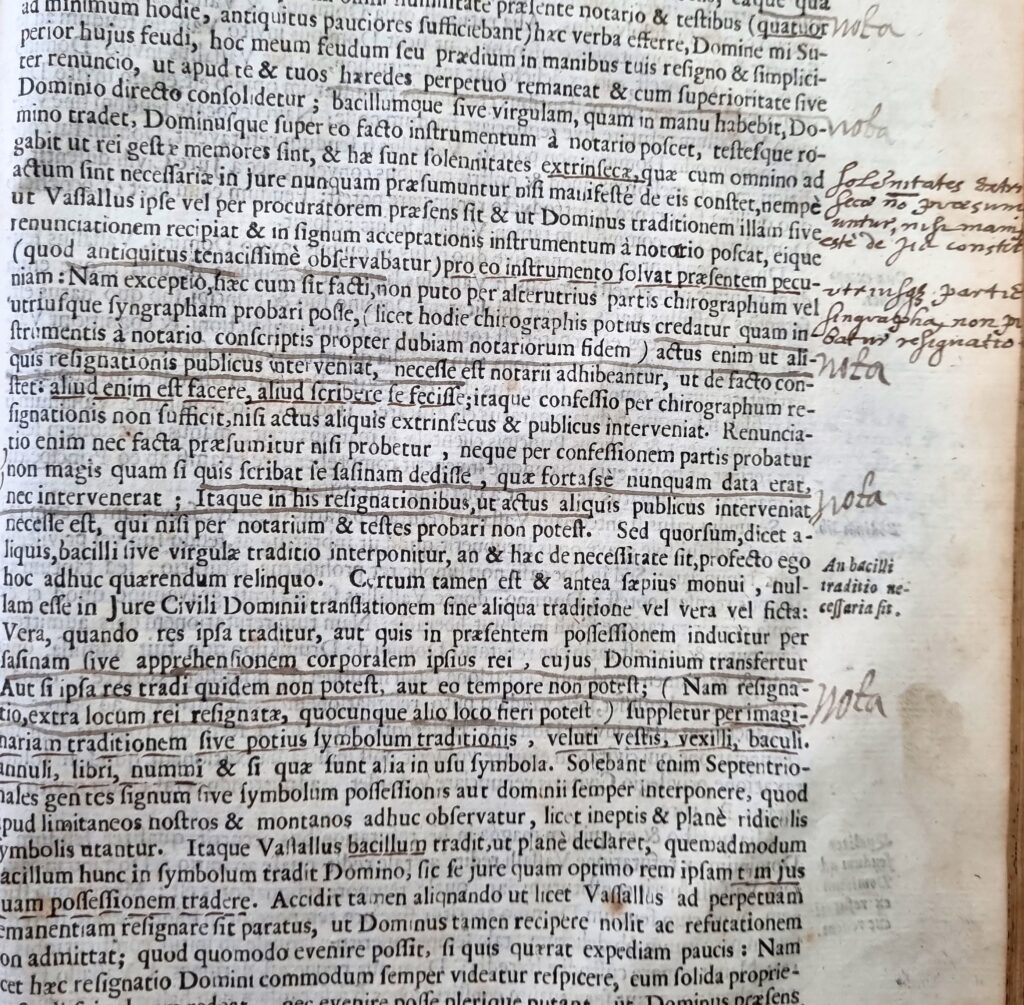

Prior to 1649, the literature of Scots Law had been largely manuscript in nature, with different kinds of useful legal texts – styles, “practicks” (procedural manuals) and specific texts – circulating in handwritten form in Edinburgh and other Scottish legal centres. The printed inheritance of Scots Law consisted of the 1609 edition of the Regian Majestatem and the printed laws of the land. In 1655, in response to the abolition of the Court of Session, one of the foremost of the manuscript texts – Sir Thomas Craig’s Jus Feudale – was brought into print for the first time.

Other, newer texts, driven by the same protective intent towards Scottish law, began to circulate in manuscript form soon after the Restoration, most notably James Dalrymple’s Institutions of the Law of Scotland of which there are three fine examples in Signet Library collections.

Stair’s magisterial work is believed to have intended the drawing together into a single system Scottish law’s disparate historical parts – the feudal law of property ownership, commissary law, civil law drawn from the ancient European tradition of Justininan and continental jurists, and decisions by Scottish judges. The same instinct would show through in William Cuninghame’s legal classes of the early 1700s. Stair first came into print, in a form revised and improved from many of the manuscript copies of his text, in 1682, contemporary to and driven by the same purposes as Sir George Mackenzie’s more educationally-inclined text, Institutions of the Law of Scotland. In the 1690s and early 1700s, Mackenzie’s Institutions would appear in cheap pocket editions, encouraging a market which the advocates Bruce and Spotiswood would enter with works of their own that quickly found their way into the new Signet Library.

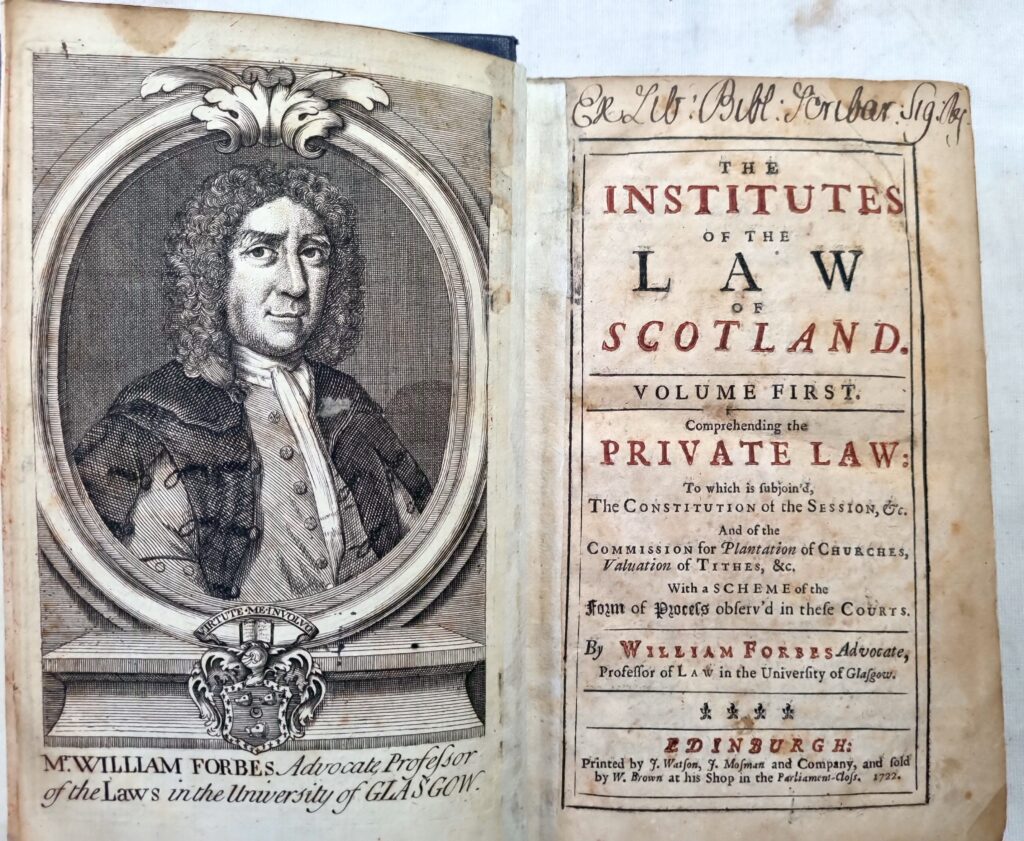

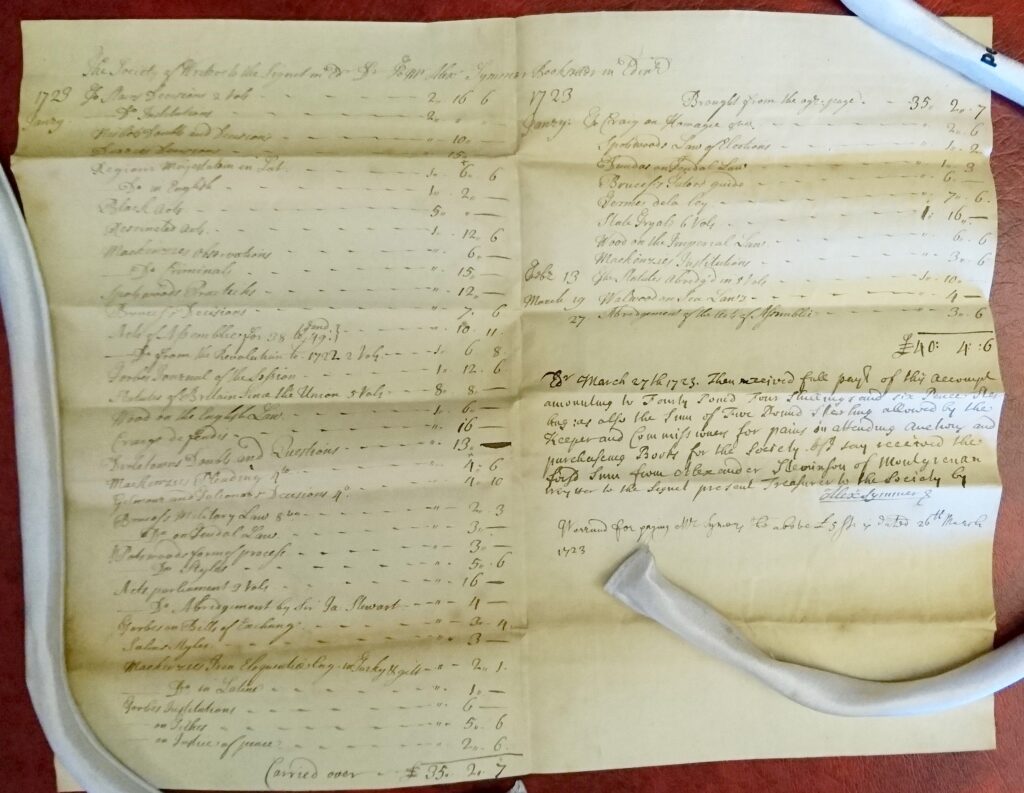

In the year of the Signet Library’s foundation, the new Regius Professor of Law at Glasgow, William Forbes, published the first volume of his Institutes of the Law of Scotland – the first of a number of attempts to move beyond Mackenzie’s handbook in the field of legal education. The flow of publications would be steady from then on, but the foundation of the Library in 1722 took place at perhaps the last point at which the entire legal printed corpus could conveniently be obtained.

Further Reading

John W. Cairns “Institutional Writings in Scotland Reconsidered” in New Perspectives in Scottish Legal History ed. Kiralfy and MacQueen (London 1984)

2. 1722: The Foundation of the Signet Library