THE WS SOCIETY ONLINE EXHIBITION 2024

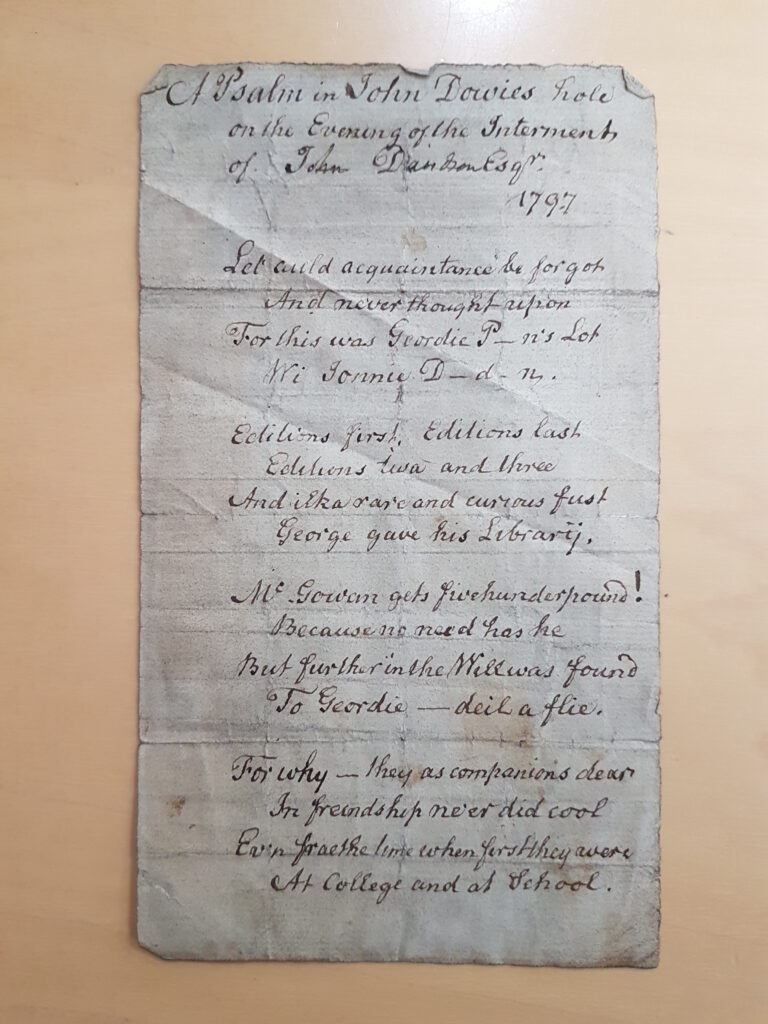

A 1797 manuscript poem written for his funeral and shown above reveals Davidson to have been part of a group of intellectuals and bibliophiles centred on the famous Johnnie Downie’s Tavern – a set which for a time in the late 1780s may have included the poet Robert Burns.

The “Geordie P_n” named in Davidson’s valedictory poem is George Paton 1721-1807. George Paton was a boyhood friend of John Davidson.

George was at the centre of Davidson’s literary circle based at Dowie’s Tavern and is remembered for having thrown open his important personal library to Enlightenment scholars such as Richard Gough, Lord Hailes and Joseph Ritson. He was not a wealthy man and had built his collection of books, antiquities, coins and prints through fierce self-denial and financial discipline. A bank collapse robbed him of his savings late in life but after his death the sale of his collections raised over £70,000 in modern terms.

Davidson’s interest in scholarship began early in his career, and he son gained an intellectual reputation within the nascent Enlightement world. William Robertson noted in the 1759 edition of his great History of Scotland that

I have added to the Appendix a Critical Dissertation concerning the murder of King Henry, and the genuineness of the Queen’s letters to Bothwell. The facts and observations which relate to Mary’s letters, I owe to my friend Mr. John Davidson, one of the Clerks to the Signet, who hath examined this point with his usual acuteness and industry.

It is worth reflecting at this point that much of the glory of the Scottish Enlightenment as it was seen at the time was explicitly historical: David Hume’s greatest literary success was in his histories rather than his philosophy, and William Robertson’s contribution, somewhat obscured now, was sufficient to secure him a place in the Signet Library’s cupola mural of the great minds of history alongside Homer and Sir Isaac Newton. In this context the WS Society’s contribution to history through figures such as James Anderson, William Tytler and John Davidson must be seen and understood.

John Davidson’s Works

Davidson’s own explicit publications were few – the demands of a career as a Clerk to the Signet were strenuous, let alone those of Deputy Keeper and few of his WS contemporaries published heavily. Although they were narrowly distributed and short in length, all of Davidson’s writings are careful, thoughtful and still worthy of attention. They can be read here.

His earliest publication seems to have been his 1771 Accounts of the Chamberlain of Scotland. In addition to a transcription of the surviving Chamberlain’s accounts for 1329, 1330 and 1331, it contained transcriptions of four “curious papers” aimed at encouraging discussion by the “able antiquarian.” The four papers included what Davidson believed was the first Scottish mention of coal in surviving literature, a document proving that the name of the mythical Scottish “King Culen” was already part of accepted national tradition by the time of Alexander II (1214-1249), a paper throwing light on the manner of the erection of landholdings into lordship, and “the only paper in Scotland,” as Davidson described it, to mention the unciate terrae, the Scottish unit of land known as ounceland.

Davidson’s words about Scottish records in the 1771 Accounts of the Chamberlain of Scotland will ring true to every researcher:

The ancient records of Scotland have met with so many disasters, and are so little known, that one who wishes to be informed of the state of that country in older times, is necessitated painfully to pick up any knowledge that can be got of it from the records of other countries, or the hints that arise from the cartularies of religious houses. Yet there are still some curious records in Scotland.

His remaining known publications came late in his life: both are believed to have been published in 1794.

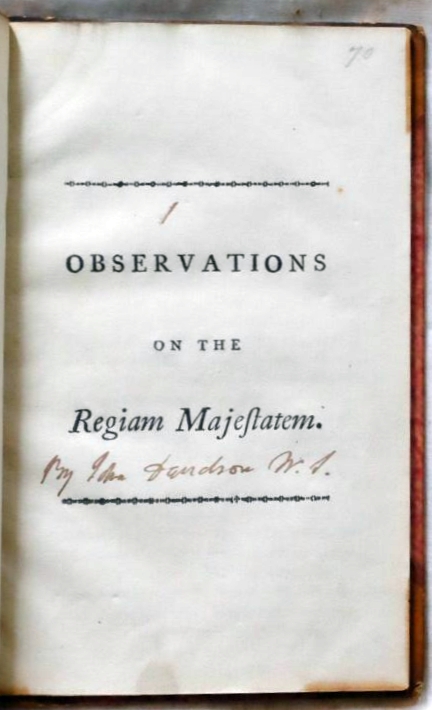

His Observations on the Regiam Majestatem was a discussion about the origins of the fourteenth Scottish legal digest of that name, which Davidson concluded to be a copy – and nothing more dignified – than the English work Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Anglie attributed to Ranulf de Glanvill (d. 1190). The origins and textual history of the Regiam remain a focus of lively historical research and debate, with a new critical edition, introduced by Professor Alice Taylor with John Reuben Davies’ editing, translation and commentary, being published in 2022 by the Stair Society.

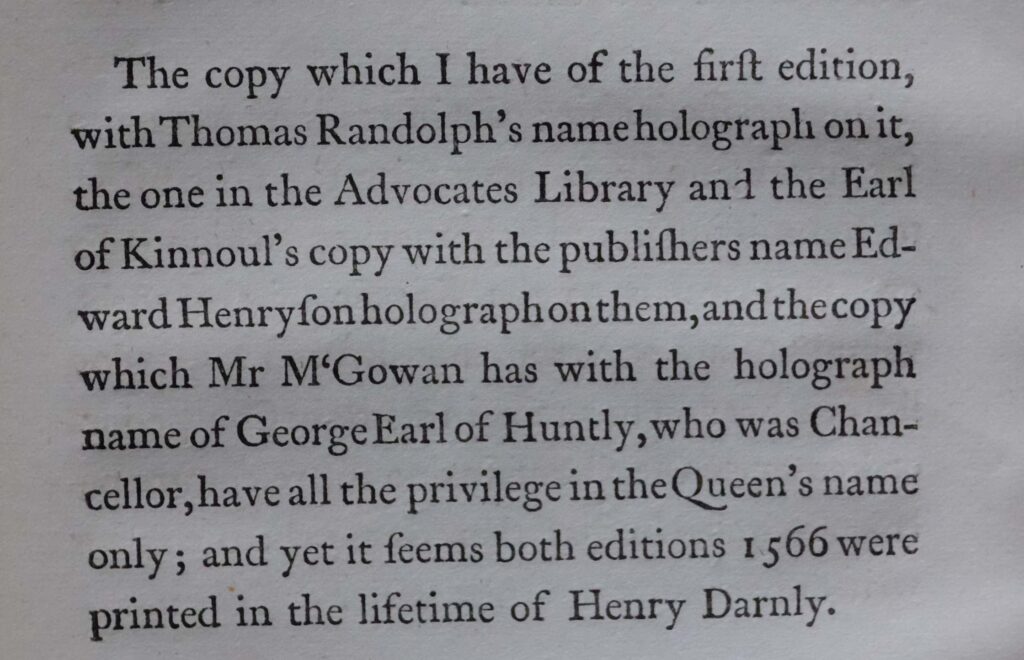

John Davidson’s Remarks on Some of the Editions of the Acts of Parliament of Scotland, also of 1794, began with a discussion of the earliest documents included in James Anderson’s Diplomata Scotia (Davidson would have had access to the Signet Library copy which was acquired at some point between its 1739 publication and 1778). But the bulk of the text concerned the two editions of the Acts of the Scottish Parliament issued by the Royal printer Robert Lekpruik in 1566 (known as the Black Acts). The first issue, dated 12th October 1566 contains a number of statutes excluded from the second (Davidson described the second issue as “castrated”). Davidson analysed these omissions and the Acts that the second issue inserts in their place, and discussed later collections of legislation such as Skene’s of 1597.

Given the extraordinary scarcity of copies of the first issue of the Black Acts it is intriguing to note that Davidson claimed to own a copy. It would be interesting to know what has become of it since.

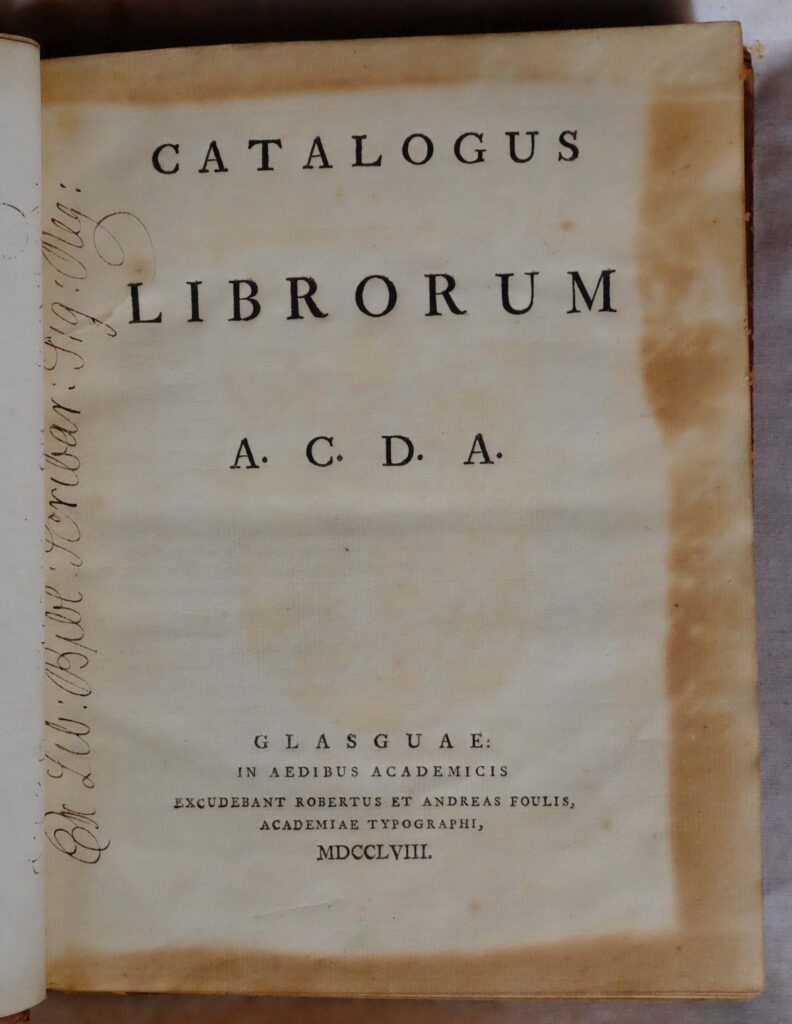

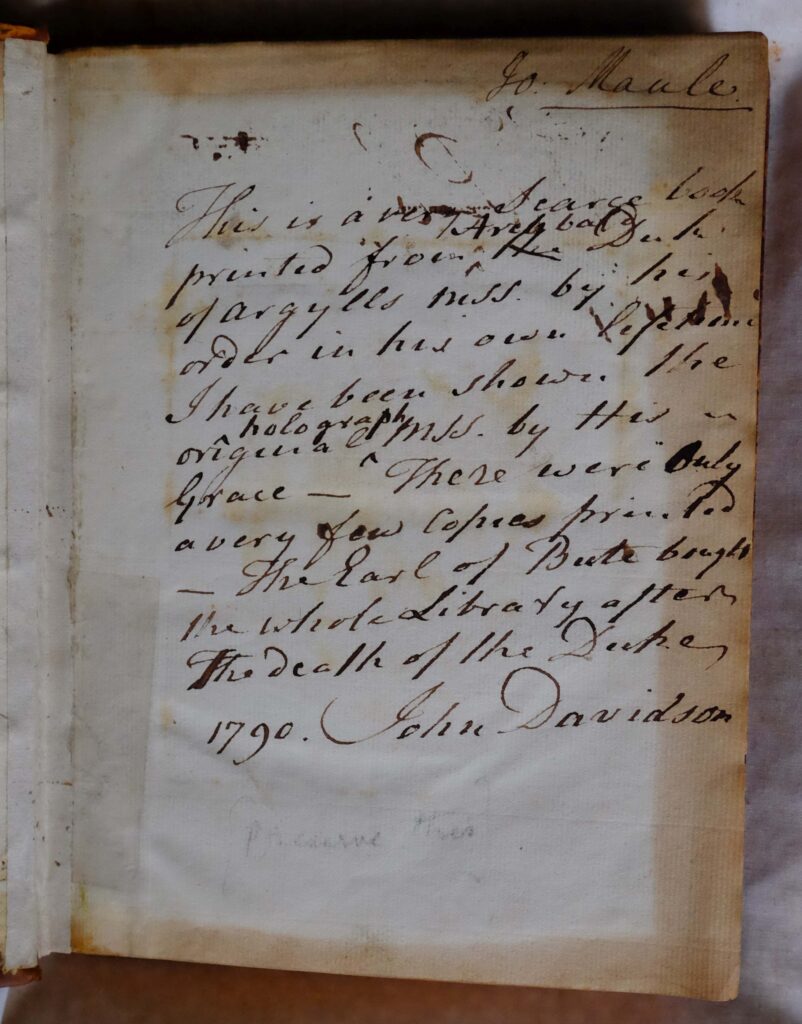

It is known that Davidson, like many lawyers of the eighteenth century, was a book collector in his own right, given that Davidson fired the starting gun for the Signet Library’s great Scottish Enlightenment Golden Age, it is only right that one of the Signet Library’s scarcest Scottish books should be in the form of Davidson’s own annotated copy – the Foulis printing of the Duke of Argyll’s library catalogue:

In August 2019, John Davidson’s Armada chest was reopened in a ceremony at the headquarters of Anderson Strathern LLP in Edinburgh attended by lawyers and historians.

3. The Signet Library in the Scottish Enlightenment

John Davidson and the Enlightenment Signet Library