The Evergreen, a Northern Seasonal was published between 1895 and 1896/7 by Patrick Geddes and Colleagues. It is often compared to The Yellow Book, The Savoy, The Pagan Review and The Green Sheaf – all part of the ‘Yellow Nineties’ progressive aesthetic movement.

Patrick Geddes was born in 1854 and was drawn to the study of biological sciences as youth. He studied biology and zoology with Thomas Huxley at the London School of Mines, before finding employment as a botanist at the University of Edinburgh (where he met Darwin), and the University of Dundee. While studying marine biology in France, he met and was inspired by the social reformer, Pierre Guilliame Frédéric Le Play and the political anarchist Prince Kropotkin. After contracting an illness in Mexico which caused temporary blindness, he was forced to give up scientific study, at which point he began to devise a way to visually represent his thoughts, ideas and plans. His ‘Thinking Machines’ (what we would now describe as a ‘mind map’) allowed him to share his new ideas on civic theory.

While lecturing in botany during the 1880s, Geddes and his wife Anna Morton, who had a career as a social worker, began putting their ideas and theories into action. At this time, Edinburgh’s Old Town had become one of the most deprived areas in Europe after the migration of the wealthy classes to the New Town in the early part of the C19, years of cholera and typhoid outbreaks, and a swelling of the population due to Scotland’s increasing industrialisation. The area had very little open space, virtually no greenery, poor access to fresh water and run down, overcrowded housing.

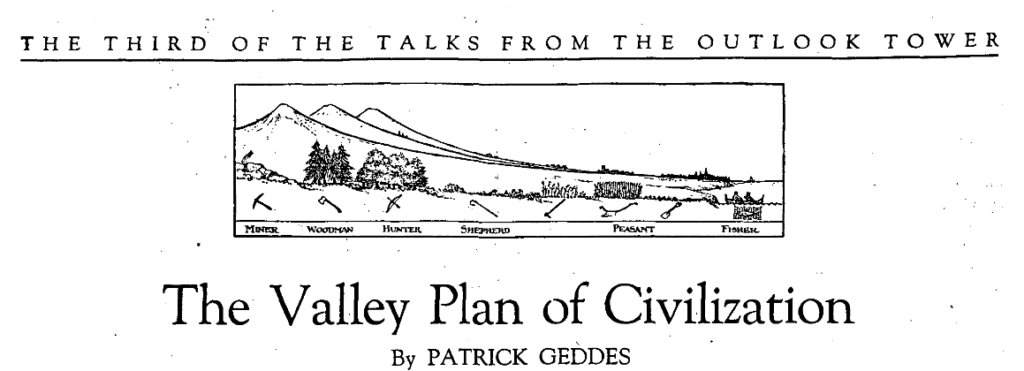

Geddes and his wife moved from their apartment on Princes Street to James Court on the Lawnmarket with a view to purchasing property and improving the area according to the theories described in his Thinking Machines. His best known concept is the ‘Valley Section’, with which he demonstrated the ideal form and functions needed to plan a town or city. This concept sees the city’s structure as an echo of the region which supports it, and functions as a model by which people can live harmoniously with their wider environment.

His study of evolution informed all his work, but in the late C19 nothing was known about DNA. Evolutionary theory was based on the study of inherited/shared traits, and the fossil record. The main schools of thought were divided between a ‘Mechanistic’ and a ‘Vitalistic’ evolutionary theory. The Mechanistic approach described in Darwin’s writing and studied by Geddes, held that evolution is a purely material process governed strictly by laws of physics. Geddes also embraced the Vitalistic viewpoint, in which evolution is driven by a ‘life force’, or ‘élan vital’, as described by French philosopher Henri Bergson.

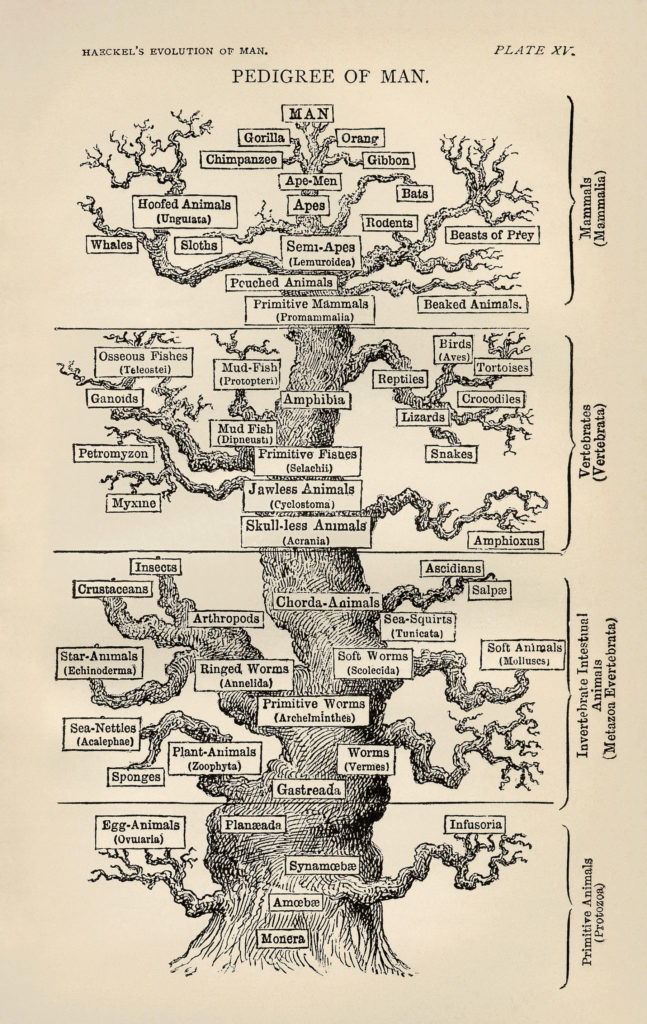

He saw this life force at all levels of human activity, from plants to large cities, and his wide ranging studies brought Haeckels theory (Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny) to his attention. The theory states that developmental stages of embryos echo the evolutionary stages of that species, for example, a chicken embryo is very similar to a fish in one of its early stages. Geddes entry in the 9th edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica on Morphology was based on his studies of Haeckel and his contemporaries – he was fascinated by the idea that a city’s structure echoes that of a cell or a plant, and is shaped by the same life force.

His work in Edinburgh’s Old Town sought to use ‘surgical’ interventions in order to improve the flow of ‘life force’ throughout the city’s structure, bringing a wide range of solutions based on his studies.

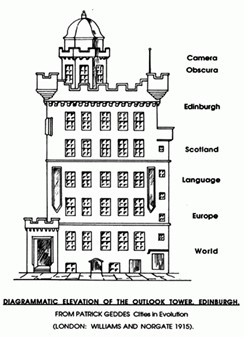

A passionate believer, not only in a multidisciplinary approach but also in seeing and making connections between people, ideas, and places. He placed a great deal of importance in education, and seeking to enthuse people with his ideas, he taught a series of Summer Schools in the 1880s, from which arose the publication ‘The Evergreen’. The classes were open to all, and featured a diverse curriculum of talks and guided walks, during which Geddes would engage the students with his ideas on biology, geography, art, and social reform. During this period, he bought the Outlook Tower, with its camera obscura, which became a focus for his teaching.

A permanent exhibition was created to demonstrate the concept of bioregionalism as it relates to town planning, as described by the French sociologist, Frédéric Le Play, whose phrase ʻLieu, Travail, Familleʼ Geddes translated to ‘Work, Place, Folkʼ. Bioregionalism is a philosophy which suggests that towns and cities should be constrained by geographical and cultural boundaries – urban areas are always seen within the context of both their wider agricultural and wild areas and cultural boundaries – language, customs etc. Geddes’s approach was to integrate the urban population and its livelihood with the wider regional environment, people moving into the green areas while nature is encouraged to thrive in the city.

Students would be able to learn about this ‘outlook’ by climbing to the top of the tower and seeing the whole region (with pointers to what lay beyond) and considering their position within it. They would then see Edinburgh, first the people and houses via the images produced by the camera obscura, before proceeding to the ground floor. Each floor showed Edinburgh in a wider context, within Scotland, Europe and the rest of the world. By giving people an understanding of their place in the world, Geddes hoped to reconnect them with their environment and cultural heritage.

The acquisition of the Outlook Tower was preceded by the purchase of Ramsay Lodge. This house had been built by the poet Allan Ramsay in 1733, and subsequently extended by Allan’s son (Allan Ramsay the artist). Geddes developed Ramsay Gardens to form Edinburgh’s first student residences.

Geddes’s title ‘The Evergreen’ was inspired by Allan Ramsay’s collection of the same name. In 1724, Ramsay published a book of poems transcribed from The Bannatyne Manuscript by George Bannatyne (1568). The Bannatyne Manuscript is an anthology of Scots poetry of the C15 and C16, with many pieces found nowhere else. Sir Walter Scott described George Bannatyne as having ‘the courageous energy to form and execute the plan of saving the literature of a whole nation’. Ramsay became a renowned Scottish Enlightenment poet after moving to Edinburgh from the Borders as a young man. Self taught, he joined Edinburgh society, making his name as a poet, playwright, publisher and librarian. ‘The Evergreen’ was Ramsay’s response to the Scottish cultural revival brought about by the Treaty of Union, a collection of poems adapted from The Bannatyne Manuscript, including some of his original work.

In reviving Ramsay’s ‘Evergreen’ title, Geddes sought to create a link with a pre industrial and pre Christian Scotland, the values and culture of which he felt were lost to the modern world. As a town planner he believed that the built environment must also be a cultural environment, with education, access to libraries, galleries etc, and ‘The New Evergreen’ would act as a focal point and hub for this activity.

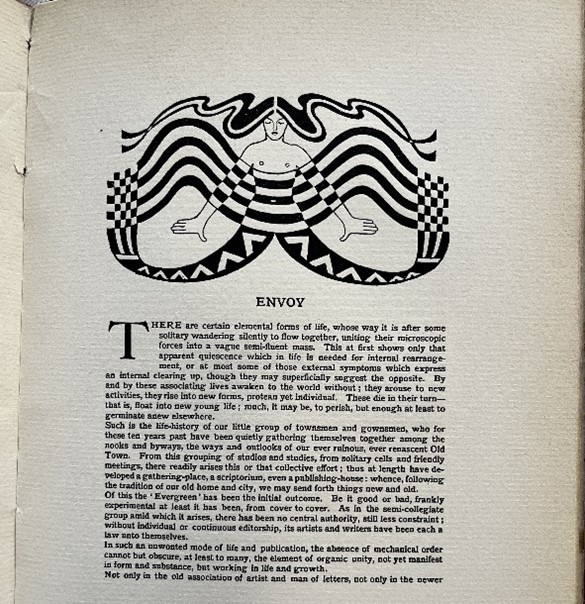

Originally conceived as a student periodical of the same name by Geddes, he subsequently met and went into partnership with William Sharp, a publishing body being formed among a few other writers and contributors, with plans made for a quarterly publication. Contributions from a variety of writers, artists, scientists, sociologists and craftspeople were encouraged, within a seasonal theme, acknowledging that all aspects of life have a cyclical aspect, and have the potential to reconnect.

William Sharp oversaw all aspects of the production of The New Evergreen, and made contributions as himself and via his alter ego ‘Fiona Macloud’ (who was also on the payroll).

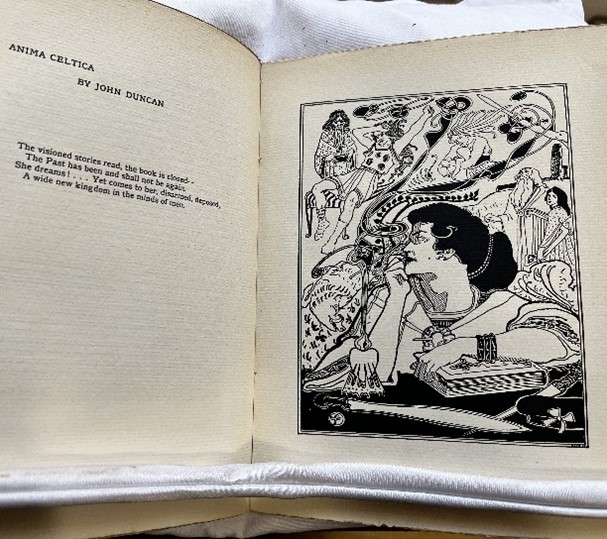

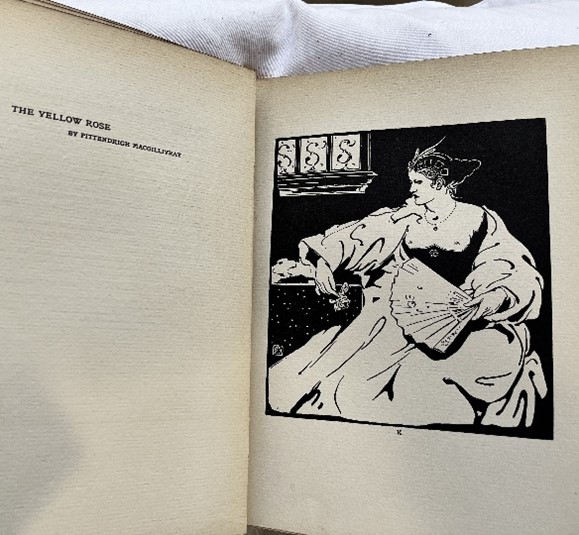

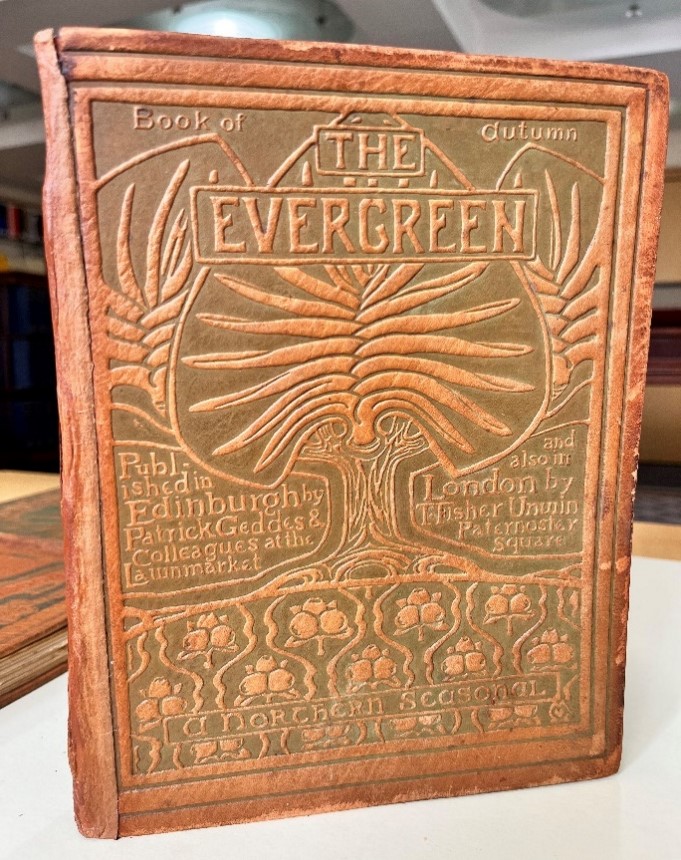

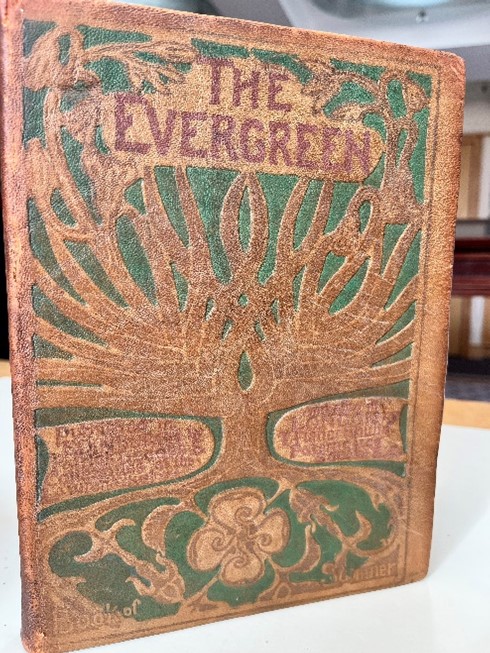

Another notable contributor was John Duncan, the Scottish Symbolist painter whom Geddes met while teaching at Dundee. Duncan had, since childhood been inspired by mythical stories and worlds, particularly the Arthurian legends. He contributed extensively to The New Evergreen with illustrations of Celtic stories and themes, which made use of Celtic visual devices such as the knotwork seen in illuminated manuscripts. Other contributors included the artist Charles Mackie, who designed the striking front cover (with its tree motif which echoes the evolutionary trees of Ernst Haeckel), the scientist J. Arthur Thomson, and Helen Hay, who was a student of John Duncan, and the sociologist Victor Branford.

The New Evergreen was well reviewed and proved influential among the educated classes. Geddes and his colleagues put a great deal of thought into the material qualities of the publication, using heavy weight paper and thick leather to give the look and feel of a substantial volume with a timeless quality.

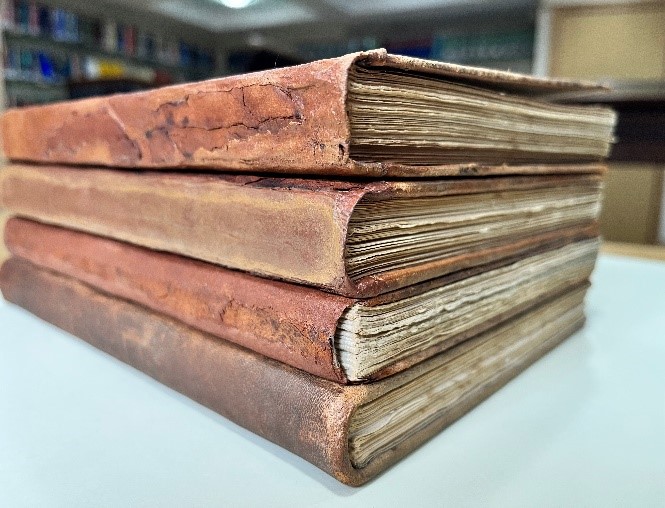

The Signet Library has all four editions of this publication, which sadly did not run beyond each of the four seasons it represented. The price needed to be set at 5 shillings in order to cover production costs and Geddes lost a significant sum of his own money in order complete each volume. The publishing company Geddes set up (Patrick Geddes and Colleagues) alongside Victor Branford and William Sharp also produced additional titles as part of the ‘Celtic Library’.

Geddes went on to form educational links with France, and oversaw urban planning projects in India and Israel. He eventually settled in Montpellier in the South of France where he set up ‘The College Des Ecossais’, with the intention of encouraging connections, both international, and between differing intellectual and philosophical viewpoints. Geddes died in Montpellier shortly after accepting a Knighthood. His influence in the fields of sociology, ecology, town planning, philosophy and art are recognised to this day, and promoted by The Patrick Geddes Trust.

The four volumes at the Signet Library were most likely bought on a subscription basis and provide a nice example of the exchange of ideas between local educational organisations.

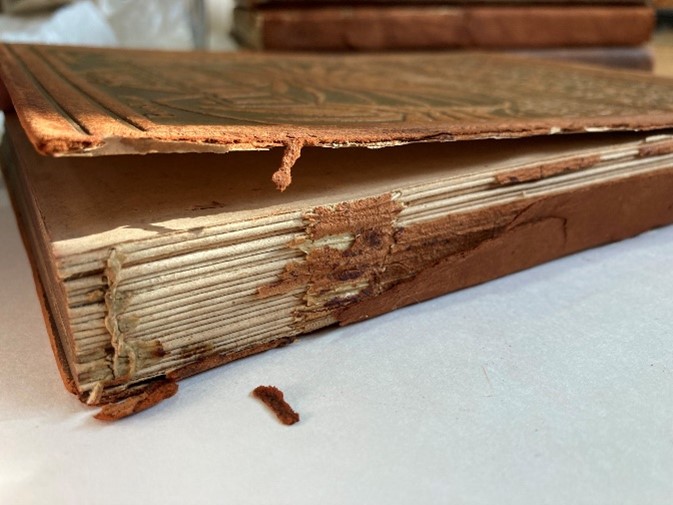

On initial examination, the volumes seemed very fragile, with dusty crumbling covers. The text blocks, however, were in excellent condition, only requiring some surface cleaning. The leather covers which are quite striking, with Charles Mackie designs done in the very fashionable Art Nouveau style, were suffering from ‘red rot’ at the edges and along the spines.

Red rot is a condition which affects low quality vegetable tanned leather – from around 1850 sulphuric acid was used to strip hides in preparation for leather production. This removed the protective calcium salts from the hides, leaving them susceptible to attack by sulphur dioxide which was increasingly polluting the atmosphere as a result of the burning of fossil fuels. Warm conditions would accelerate the process – the leather becomes very acidic, causing the fibres to degrade and results in leather which loses its strength and eventually becomes very powdery. Fortunately the designs on the front and back boards have not been affected by red rot, probably because this area is less exposed. The spines and edges of the boards were treated with a form of cellulose mixed with isopropyl alchohol (known as Cellugel) in order to consolidate the crumbling leather. Missing parts of the spine on three of the volumes were repaired with mulberry/kozo repair paper and acrylic paint was used to match the paper to the colour of the books. The volumes can now be accessed again, giving us an insight on some of the earliest examples of Celtic Revivalist writing in Scotland.