THE WS SOCIETY ONLINE EXHIBITION 2024

For the first fifty years of its life, the Library founded by Thomas Pringle would remain a purely professional legal affair housed in a Writers Court tenement. In 1778 a new Deputy Keeper to the Signet, John Davidson (d. 1797) opened the doors to the new thinking sweeping Scotland, giving birth to a new Signet Library whose collections would typify and represent the very best of the Scottish Enlightenment and more.

Davidson’s programme was lofty and sweeping. Henceforth, “the best books on all subjects” would be collected, not just law and jurisprudence. A new and grander home for the WS Society and its Library was sought, and by 1784 Writers Court had grown into a three storey complex with a double height meeting room.

The shift from a legal to a general Signet Library reflected a new WS Society that could look to scholars in its membership such as William Tytler (1711-1792) and Walter Ross (1738-1789) and demonstrate that a lawyer’s role could lay claim to the widest socio-cultural remit, requiring access to works on all aspects of life and thought. The Writers’ Library became a reflection and commemoration of lawyers’ research and writing lives as well as a friend to their legal duties.

John Davidson’s Early Life and Apprenticeship

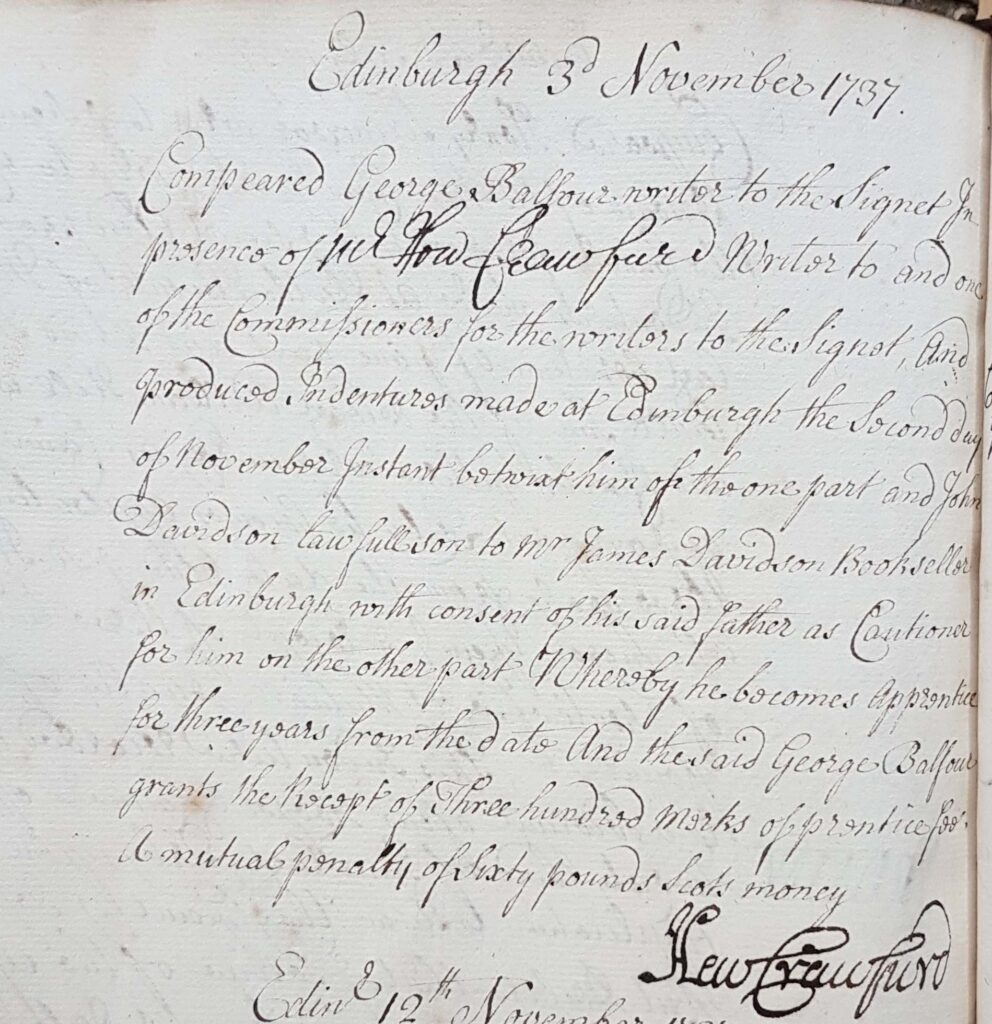

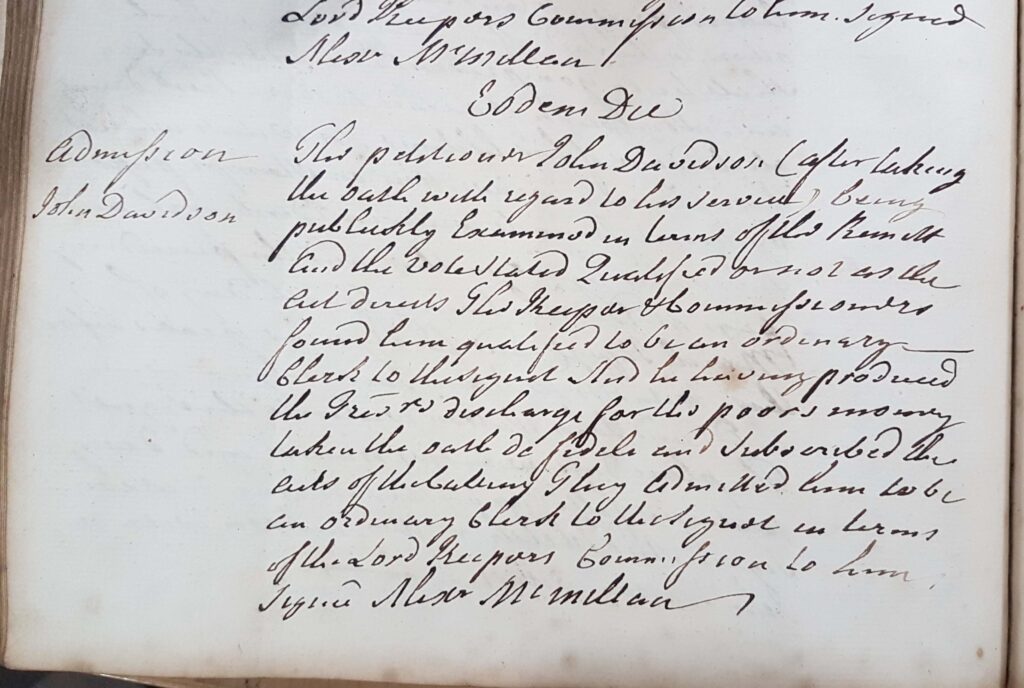

The WS Society’s record of the future Deputy Keeper of the Signet John Davidson’s entry into his legal apprenticeship with George Balfour in 1737.

Davidson was the son of James Davidson, the printer to the Church of Scotland. His mother died soon after his birth. His apprenticeship with Balfour was to last five years, but his father’s death in 1743 meant that it would be 12 years before his could become a full Writer to the Signet. Successful as he was professionally, his private life was another matter. His only son died in early childhood, and his property passed beyond his family after his own death in 1797.

The Books of John Davidson’s Signet Library

It was as Deputy Keeper to the Signet in and after 1778 that John Davidson’s great contribution to Signet Library history occurs – his decision that the Society’s books should move from a small professional collection of legal texts into an Enlightenment Library of the “best books on all subjects”

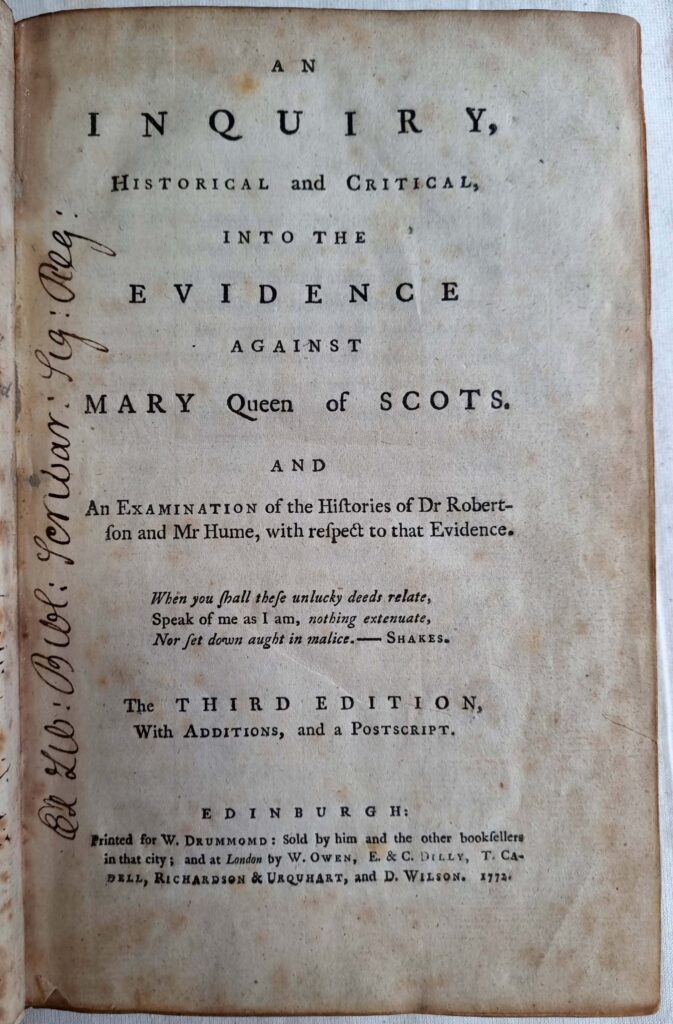

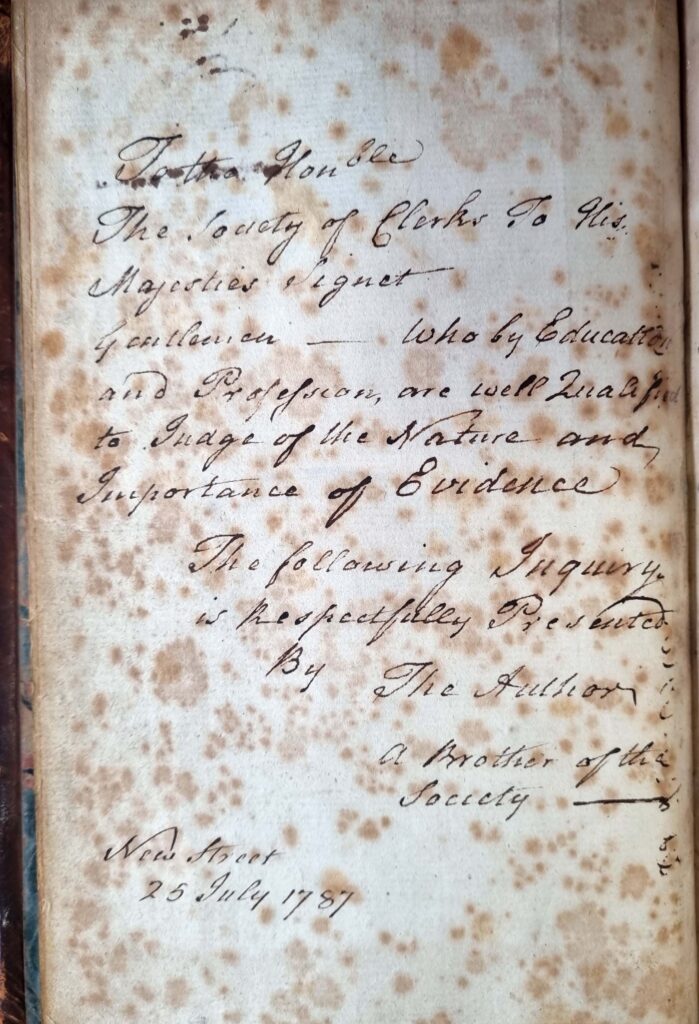

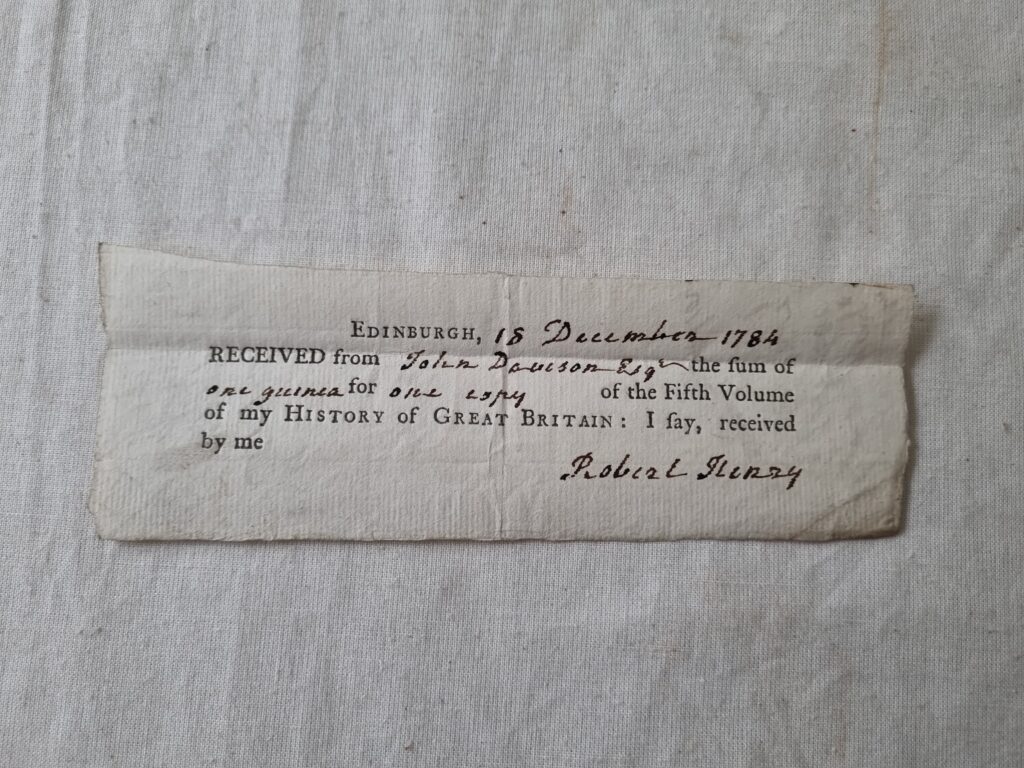

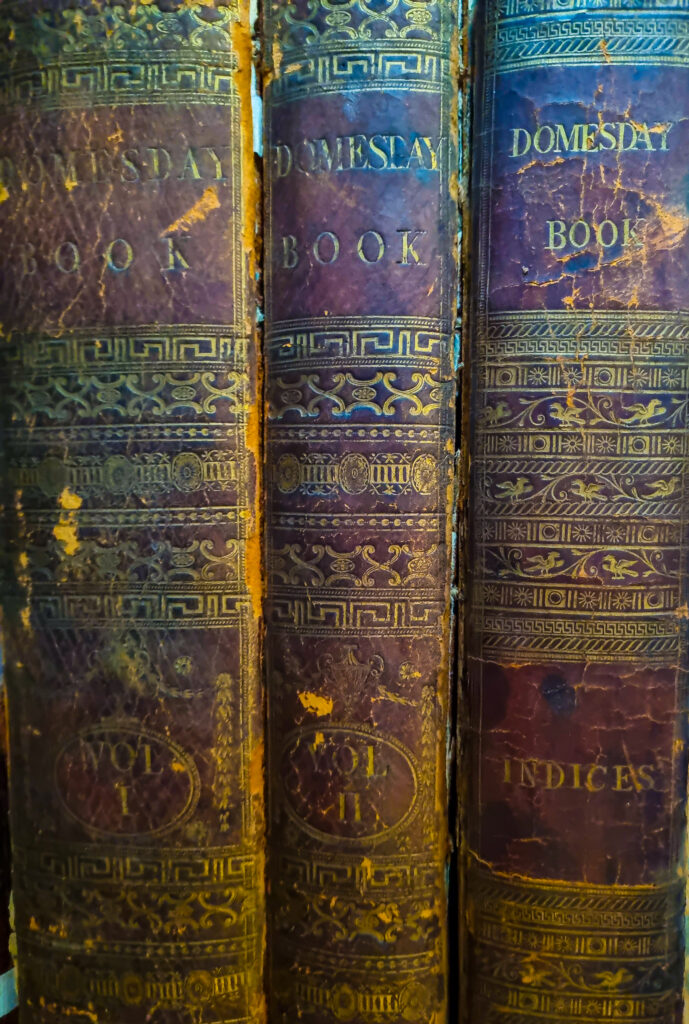

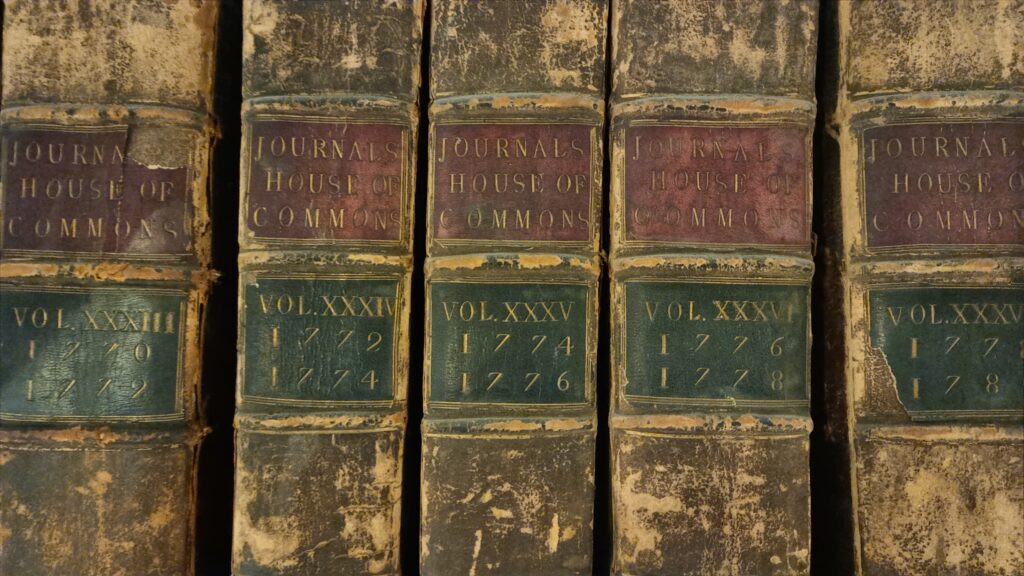

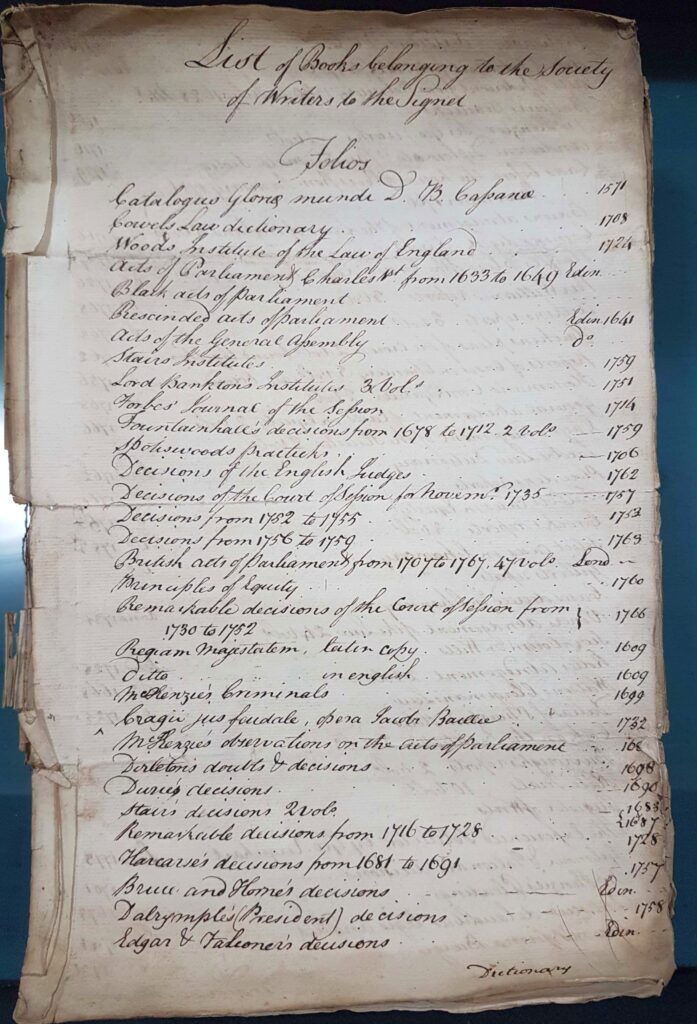

As we have seen from Writer to the Signet William Tytler’s donation of his historical work on Mary Queen of Scots, the Enlightenment Signet Library under John Davidson quickly benefitted from donations, and by 1792 the collection amounted to over 3000 volumes. Many of these early acquisitions and donations remain in the collections today:

The chance survival of a manuscript handlist of the Signet Library’s books along with a cache of booksellers’ invoices from the period, will eventually allow us to track the early growth of the Signet Library and gain some idea of the thinking behind its early development.

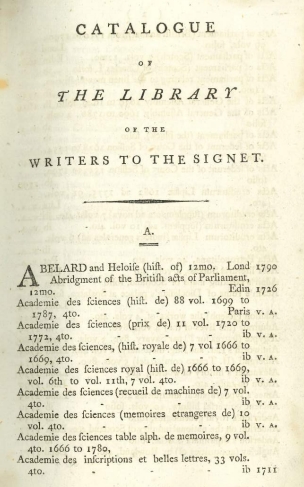

The First Printed Catalogue, 1792

Towards the end of John Davidson’s twenty year service as Deputy Keeper of the Signet, a pocket-sized printed catalogue of the Library was released. Attributed to John Cameron, the de facto Librarian of the time, it appears to have been entirely unheralded in the public realm. Copies are exceptionally scarce today and there is no hint that it was intended for use outwith the Society membership. The catalogue consists of 97 pages, with 60 of them left blank for future additions to stock to be added in manually.

In his The Signet Library Edinburgh and its Librarians 1722-1972 (Edinburgh: The Scottish Library Association, 1979), George Ballantyne waxes cool on the collection at this stage of its life:

Entries number somewhat over 1000, but allowing for duplication of authors and titles, the actual number of books is rather less.. The collection had a distinctly miscellaneous flavour, running from long sets of the transactions of the world’s most learned societies to the humble single volume duodecimo Treatise on the Office of Messenger.

Nevertheless, the basis for the Library’s Georgian Golden Age was already in place, with most major subjects at least represented and some – genealogy, history and travel – represented well.

By 1792, however, the Library’s first Enlightenment leaders were fading from the scene. Walter Ross died suddenly and unexpectedly in 1789. 1792 saw the death of William Tytler, David Erskine had died in Naples the previous year, and Davidson himself would, as we have seen, pass away in 1797. Their absence would open a vacuum, and it would be a difficult decade for the Library and its collections before their shoes were filled.

Further Reading

For lawyers’ libraries, see Dr. K.G. Baston Charles Areskine’s Library: Lawyers and Their Books at the Dawn of the Scottish Enlightenment (Brill 2016)

For John Davidson’s professional world, see John Finlay Legal Practice in Eighteenth Century Scotland (Brill 2015) and John Finlay The Community of the College of Justice: Edinburgh and the Court of Session 1687-1808 (Edinburgh 2012)

For the Scottish Enlightenment, see Jean-François Dunyach and Ann Thomson, eds. The Enlightenment in Scotland: national and international perspectives (Oxford 2015)

For the Scottish book in the Enlightenment, see Richard Sher The Enlightenment and the Book (Chicago 2006); also Stephen Brown and Warren McDougall The Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland: Vol. 2 Enlightenment and Expansion 1707-1800

3. The Signet Library in the Scottish Enlightenment

John Davidson and the Enlightenment Signet Library