THE WS SOCIETY ONLINE EXHIBITION 2024

James Anderson’s appointment as Scotland’s Postmaster in 1715 came about as a consequence of the change in the political air that followed the ascension of George I. The arrival of the new king also brought change to the Writers to the Signet themselves after half a century of instability and almost annual changes of Keeper. The consequences for the Society had been dire, as an anonymous communication to the King’s minister Lord Harley in London in 1711 commented:

MEMORANDUM relating to the SIGNET of SCOTLAND.

The Secretaries of Scotland by their commission were constituted keepers of the Signet, impowered to make deputies and appoint clerks and writers to the Signet. They appointed their friends to be their deputies who were above troubling themselves with the business, and therefore those deputies made sub-deputies who kept the Seal and Records and were generally inconsiderable people. They accounted for the fees and performed the service for what they called “Drink Money,” which was what they could get for despatch.

The Drink Money often came to more than the fees. The business of this, as well as of the Great and other Seals, was transacted at Public Houses, where things were sealed; and so little care was taken in admitting Writers to the Signet, through whose hands all their conveyances and process pass, that they are now become very numerous and most of them so ignorant that many of their writings are neither to be read or understood.

To remedy this evil, it will be proper to put the Signet into such hands as will take care of the business that belongs to it, and to give no other power by the commission than barely what belongs to the Signet and the admitting of clerks or writers. It may be committed to the custody of one or more, but whoever hath it ought not to execute it by deputies.

If this falls into careful hands, it is probable some clerkship will be brought into that country, to which, at present, they are great strangers, the records will be kept in some order, and the dignity of Her Majesty’s Seal will be restored. It will be contended by those that are for setting up a Scots Secretary that there will be wanting somebody to dispatch business in London, but there is very little in that pretence for all things that relate to the revenue are under my Lord Treasurer’s care and must pass through the Treasury. There will be little other business, perhaps now and then the making of a judge or other officer, for which there are forms of warrants in the Scots Secretary’s books.

Unsigned. [Attributed to Baron Scrope]

Oxford’s docket. Received July 14, 1711.

Recorded in Report on the Manuscripts of His Grace the Duke of Portland (London: Historical Manuscripts Commission, HMSO, 1931 p.387

Change would not be long in coming. A new leader emerged from within the Society’s ranks whose actions in office would forcibly alter the Society’s trajectory for the following century. His name was Thomas Pringle and he became Deputy Keeper to the Signet in 1716. Pringle was the fourth son in a powerful Scottish legal family: one brother was a senator of justice and another was the Secretary for War. Pringle stemmed from a locus of political power that would make him hard to dislodge, and he used this position well, reforming every aspect of WS Society life and practice.

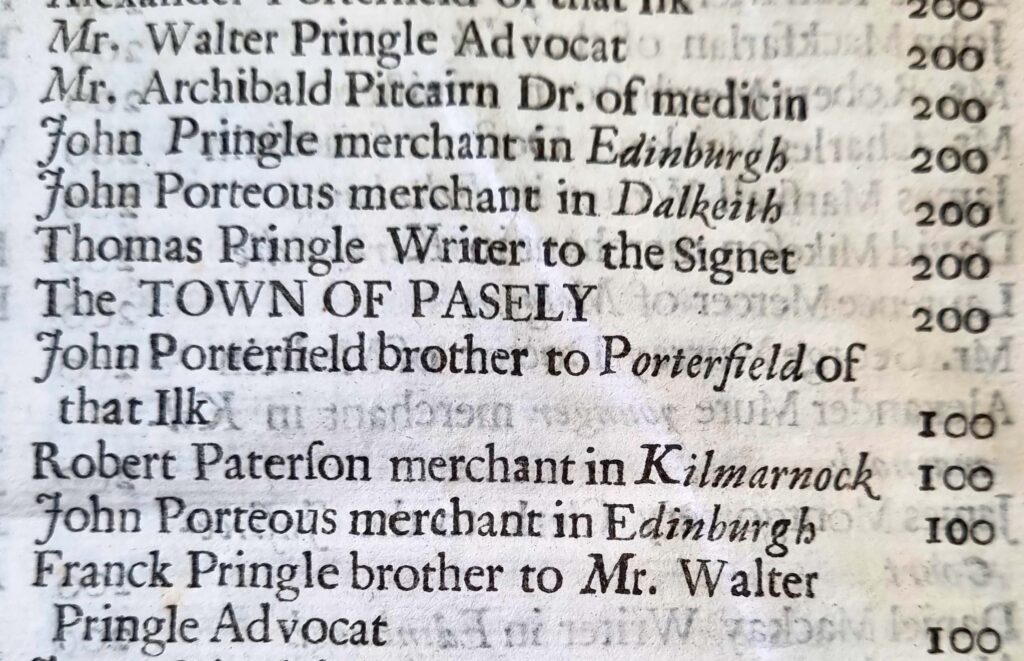

Although Thomas Pringle was strictly a lawyer, he was nonetheless interested in history, literature and learning: he is listed as a subscriber for instance to Edward Chamberlayne’s Magnae Britannicae notia, or, the present state of Great Britain. (London: T. Goodwin, 1708). He was also a patriot, a subscriber to the unfortunate Darien Scheme of 1697.

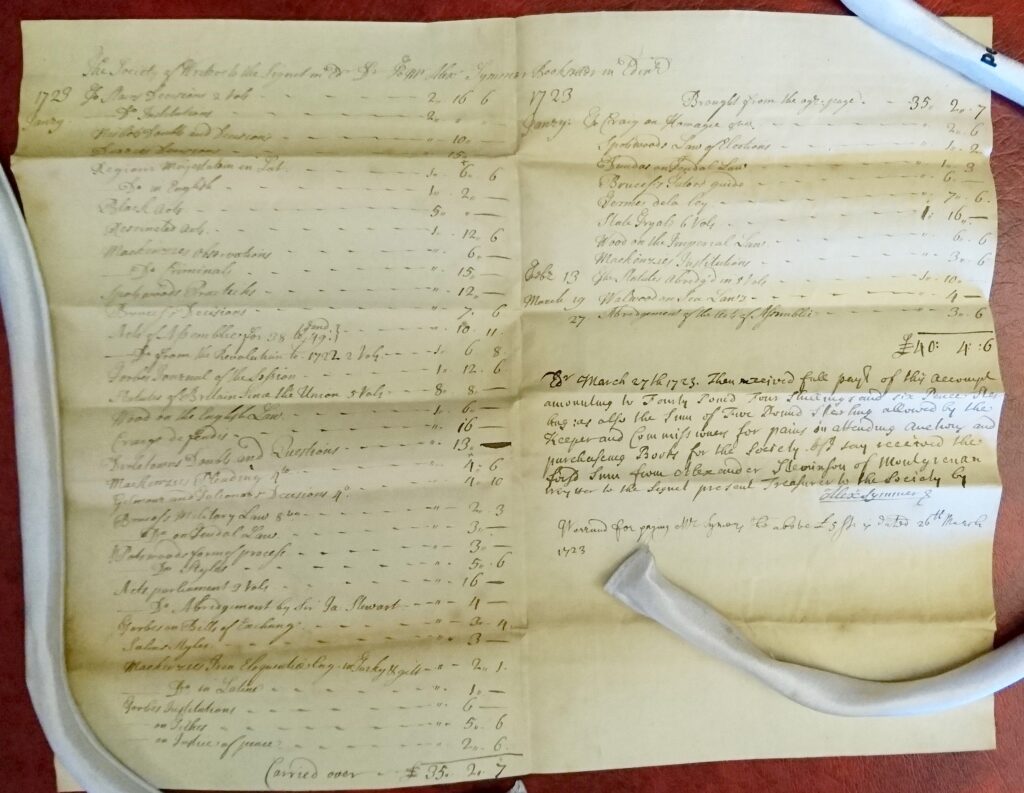

In 1722, Pringle and his WS Society Commissioners turned their eyes towards the future and decreed that henceforth the Society’s policy was to build a library containing a copy of every Scottish legal text and to maintain complete sets of legislation and the Acts of Assembly of the Church of Scotland.

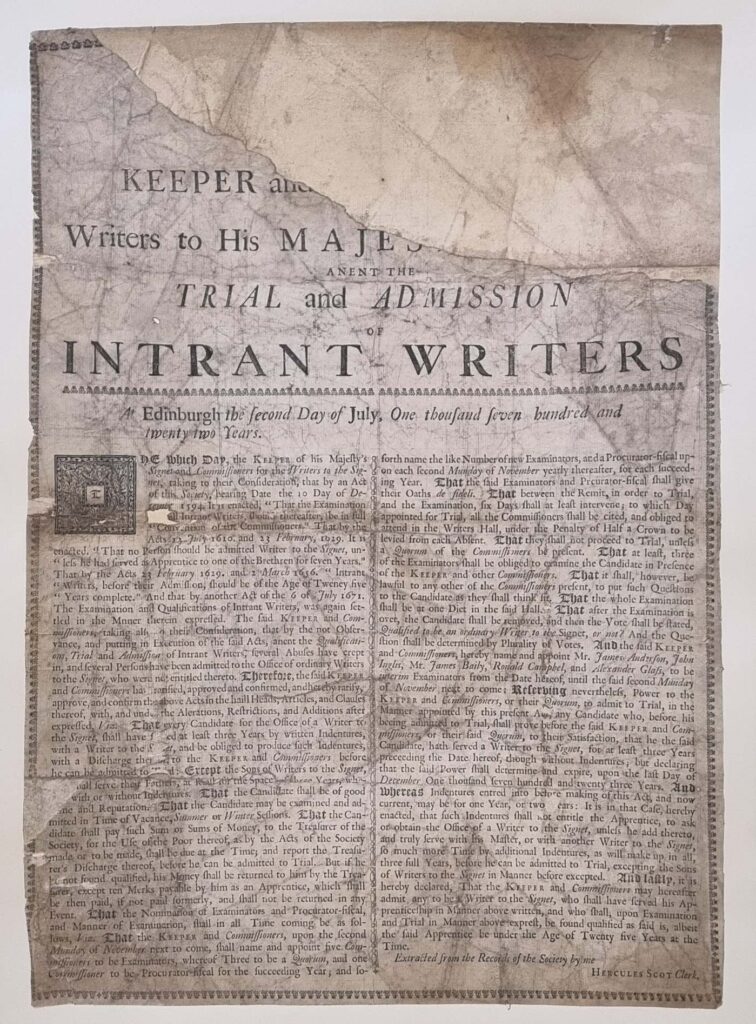

The creation of the Library was almost certainly planned from the beginning of Pringle’s keepership. The Clerk of the Society, Hercules Scott WS, obtained office in 1719 aged sixty, having only that year completed a WS apprenticeship under Pringle. Scott was one of a small group of trusted people Pringle was building around himself, and when the Library was created in 1722 it was immediately placed under Scott’s care.

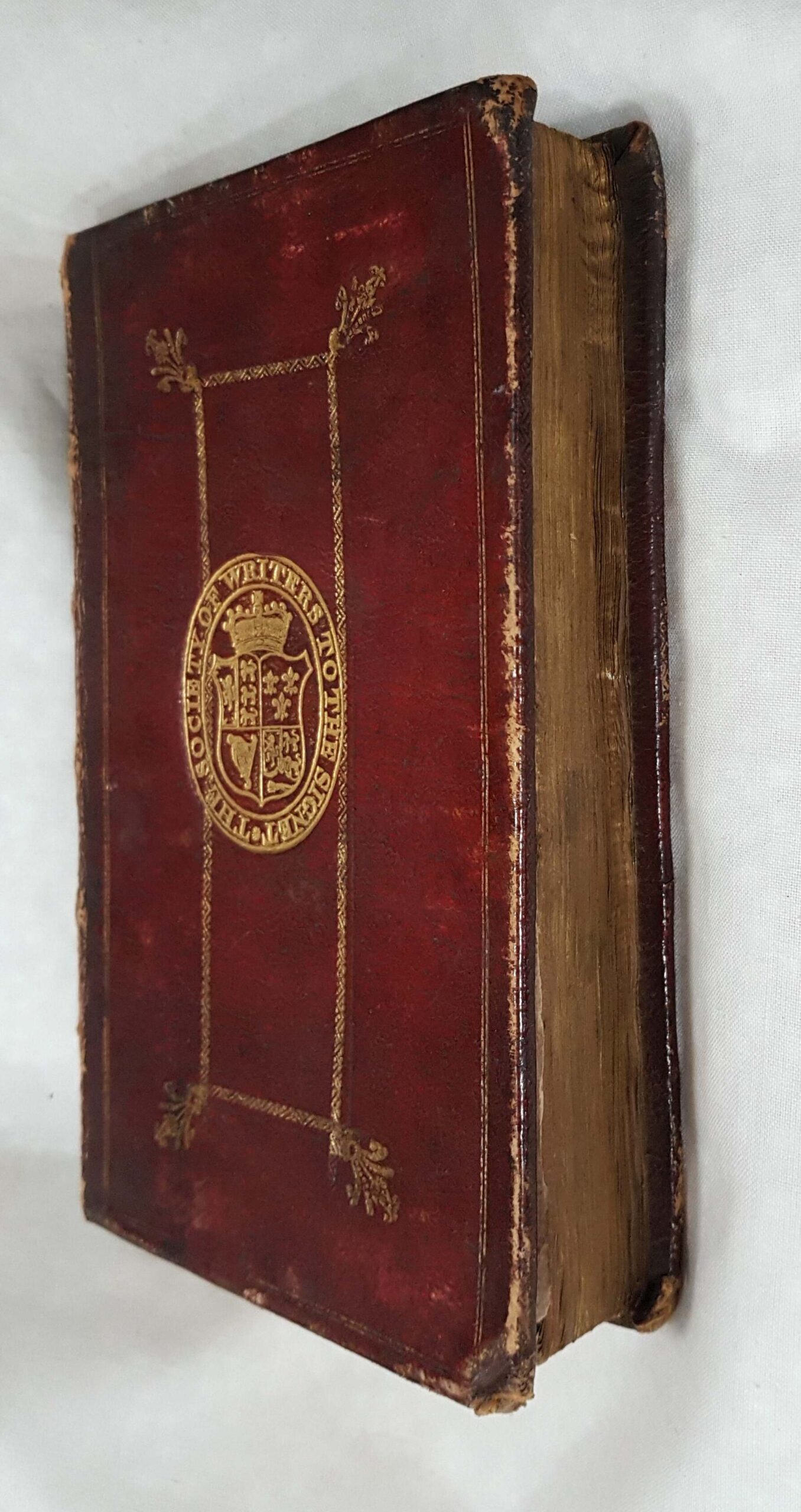

Almost all of the original 45 volumes that made up the Library of the Clerks to His Majesty’s Signet remain in the collection today.

Unfortunately we know little of Thomas Pringle the man. When he died in 1735, the great era of legal memoir and obituary still lay ahead. A window onto him was briefly opened by the Gentleman’s Magazine after Pringle’s passing, where he was described as “esteemed one of the most knowing Gentlemen of the profession, and had so fair a character, that his death is universally regretted”

The Signet Library’s First Book

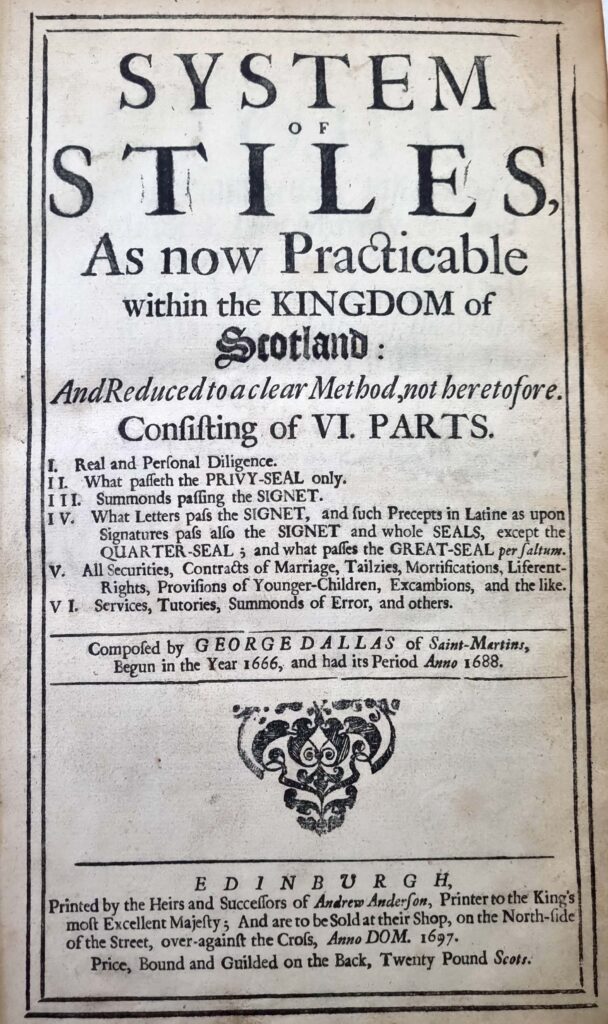

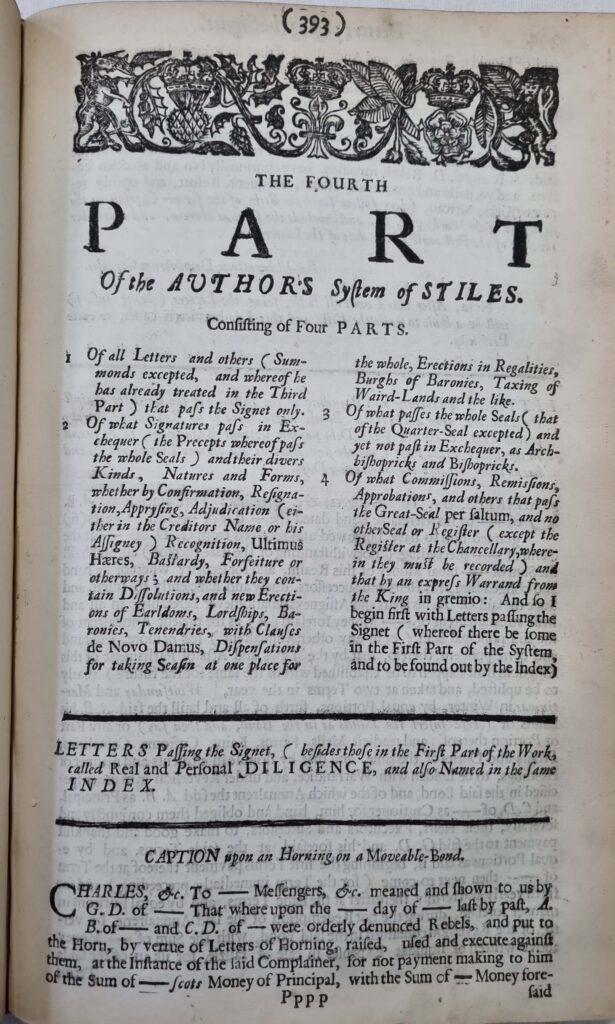

Although the Signet Library was founded in 1722, the WS Society’s first book had been at Writers Court since 1697. This was Dallas’s Styles, a collection of sample forms and contracts for lawyers created by Sir George Dallas WS. It was hugely successful – Sir Walter Scott mentions it in his novels – and so widely used was it that it is still a required work of reference for modern lawyers today. Dallas employed real documents for his styles, and the book now represents a key primary text for the lives and contexts of the individuals whose documents Dallas used.

Lawyers’ Libraries in the Early Enlightenment

Scottish lawyers were among the most significant builders of libraries in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These collections took a broad view of what a lawyer needed both as a professional and as a person of culture and refinement. In the best surviving example, the library from Newhailes House near Edinburgh (collected over decades by the Dalrymple legal dynasty), books on law were accompanied by works on philosophy, ancient literature, history and travel, mirroring the broad approach of the legal education of the time.

Thomas Pringle’s Signet Library was by contrast a highly focussed professional collection devoted entirely to the practical matters of legal practice. Its books were not chosen for the Society’s greater prestige, not were they intended to support legal study by apprentices. The collection’s intent is clear from its contents: the raising of professional standards to the highest level possible.

Further Reading

William Anderson, “Pringle” in The Scottish Nation

Or the Surnames, Families, Literature, Honours and Biographical History of The People of Scotland (Edinburgh 1863)

Thomas Graves Law, “The Library” in A History of the Society of Writers to Her Majesty’s Signet.. (Edinburgh 1890)

George Hodge Ballantyne The Signet Library Edinburgh and Its Librarians (Scottish Library Association 1979)

2. 1722: The Foundation of the Signet Library