An Illustrted Essay by Joanna Hockey in Introduction to the Signet Library Almanacs Collection

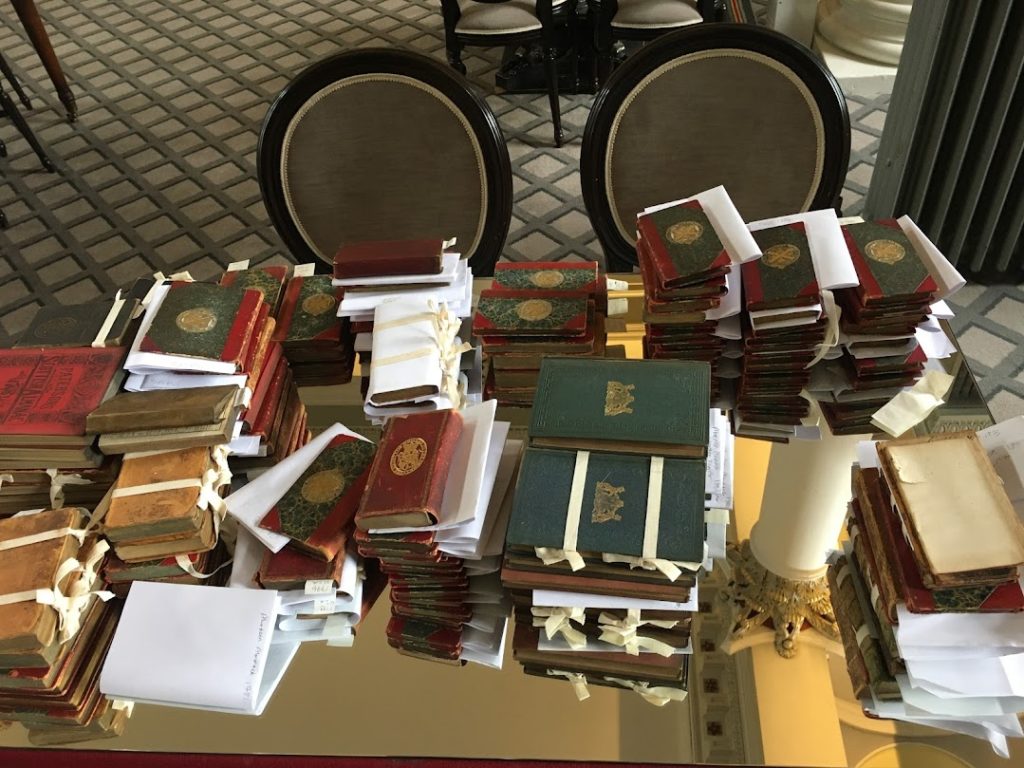

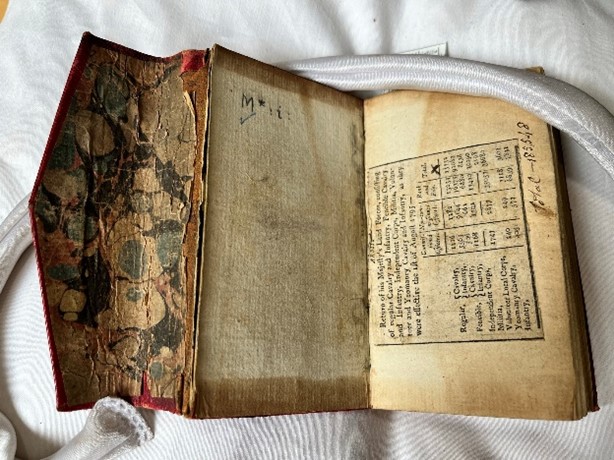

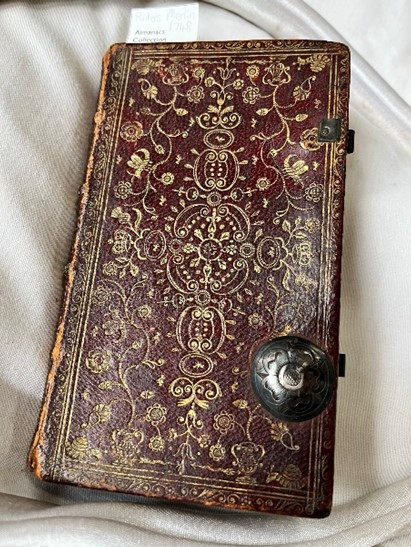

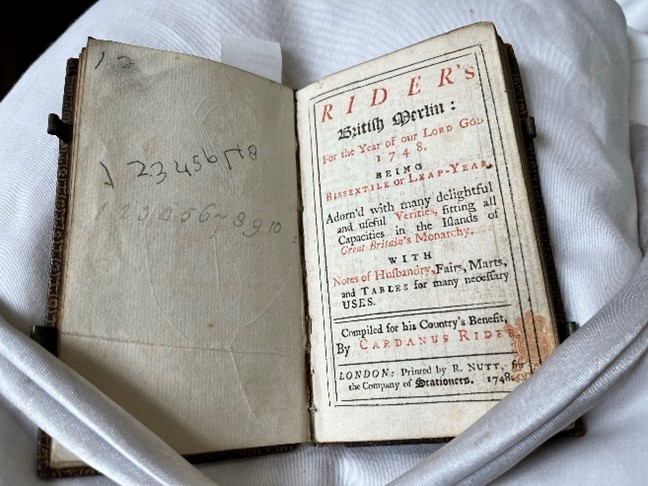

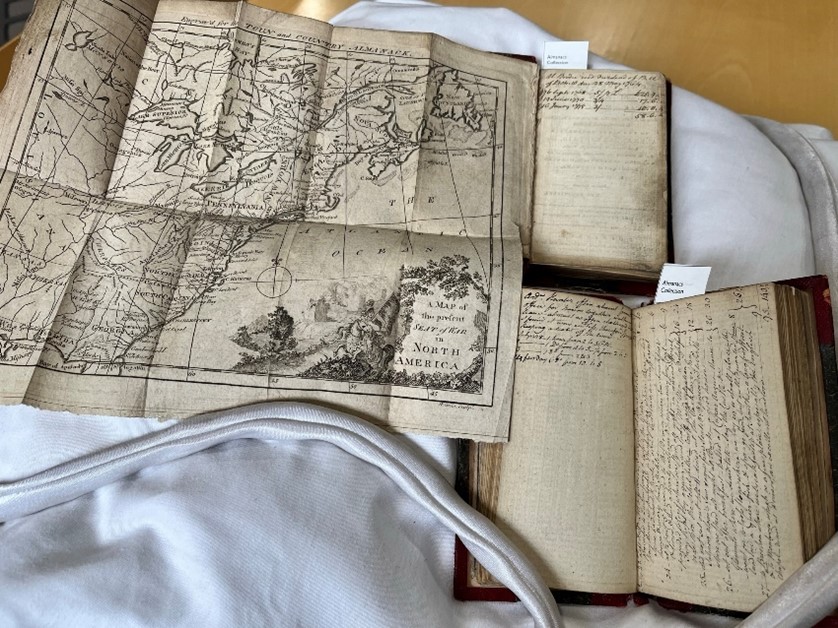

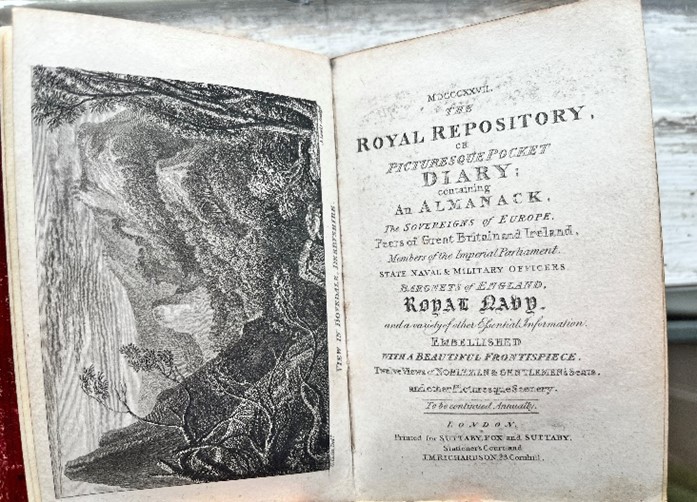

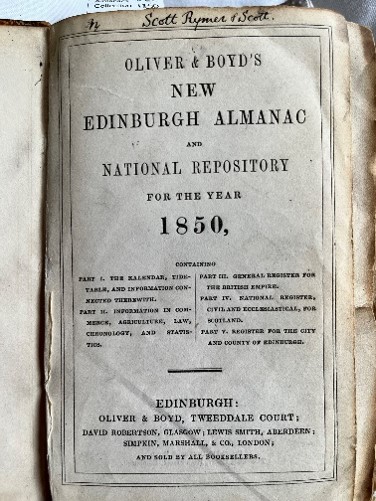

In 2019 I began a survey of The Signet Library’s collection of almanacs, the plan being to simply catalogue and conserve the volumes. Each volume is appealingly pocket sized, often leather bound, and shows many signs of the years of wear and tear.

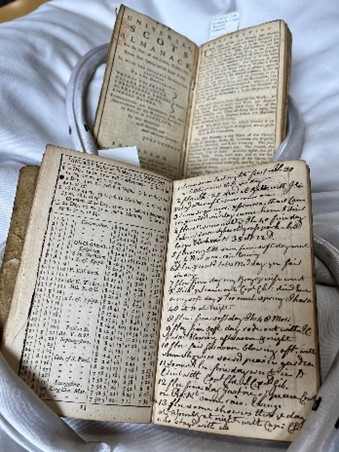

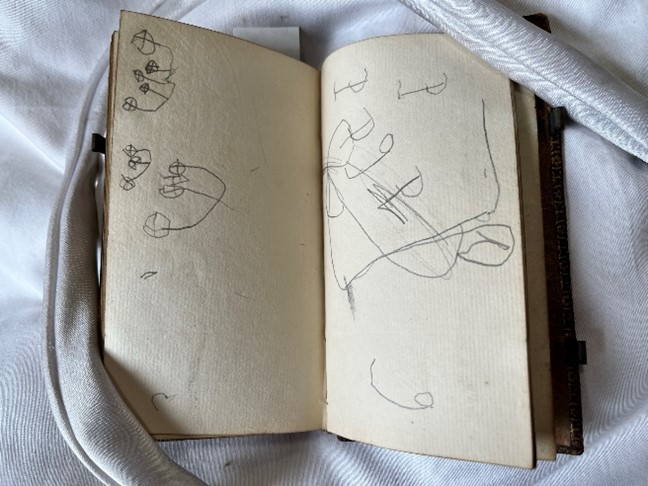

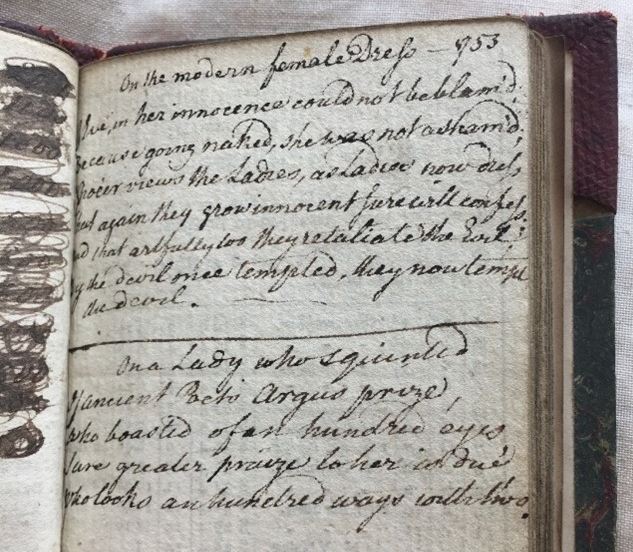

Upon opening, we find lists and charts, which must have been of daily use to the owner, but most intriguingly, we find many handwritten notes. The almanacs date from the mid C18 to the early C19, which makes these notes almost 300 years old. Although tiny, due to lack of space, the notes give us an insight into the way that these books were used, and into the owner’s lives.

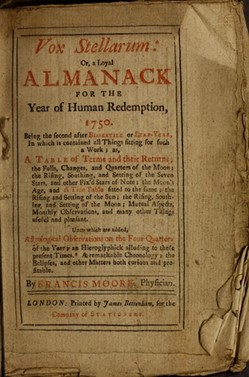

Clearly there was far more to these publications than is initially apparent, first and foremost being their popularity. They were designed to be used for one year only, in the way of a modern pocket diary or calendar, but Bernard Capp (Astrology and the Popular press. English almanacs 1500-1800 (Faber, 1979)) estimates that 1 in 3 households owned one by the 1600s. Their ephemeral nature and the high price of paper at the time meant that very few survived, as they were used for a wide variety of household purposes. Surviving copies would have probably belonged to wealthier educated people, who wished to preserve the notes written inside them.

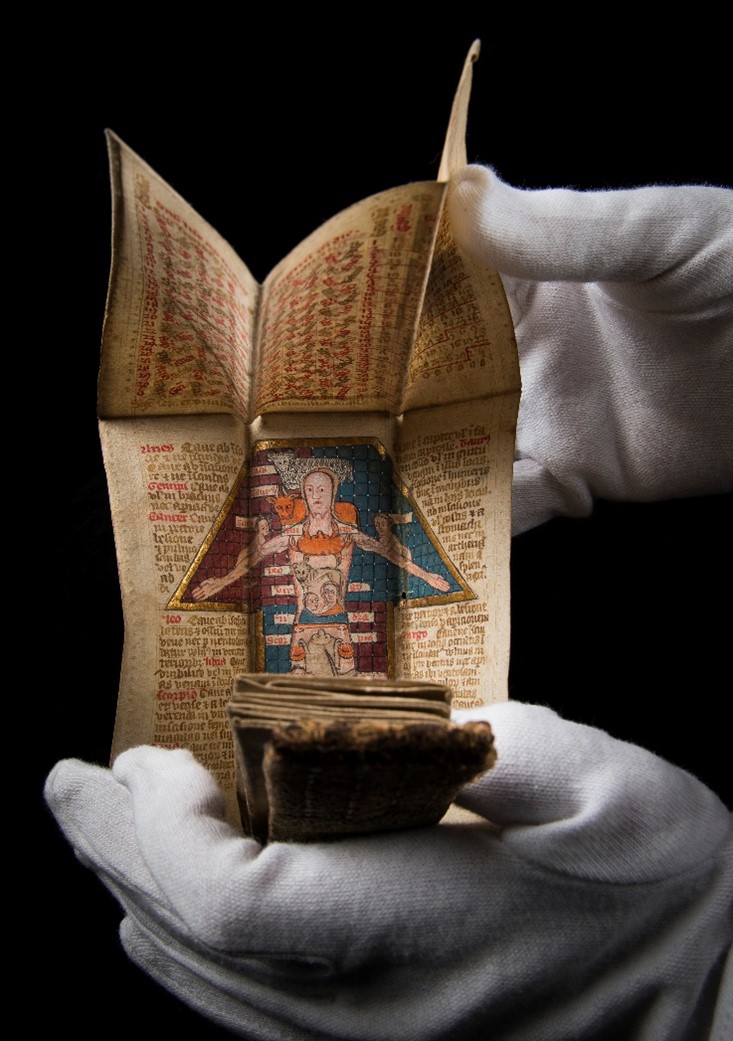

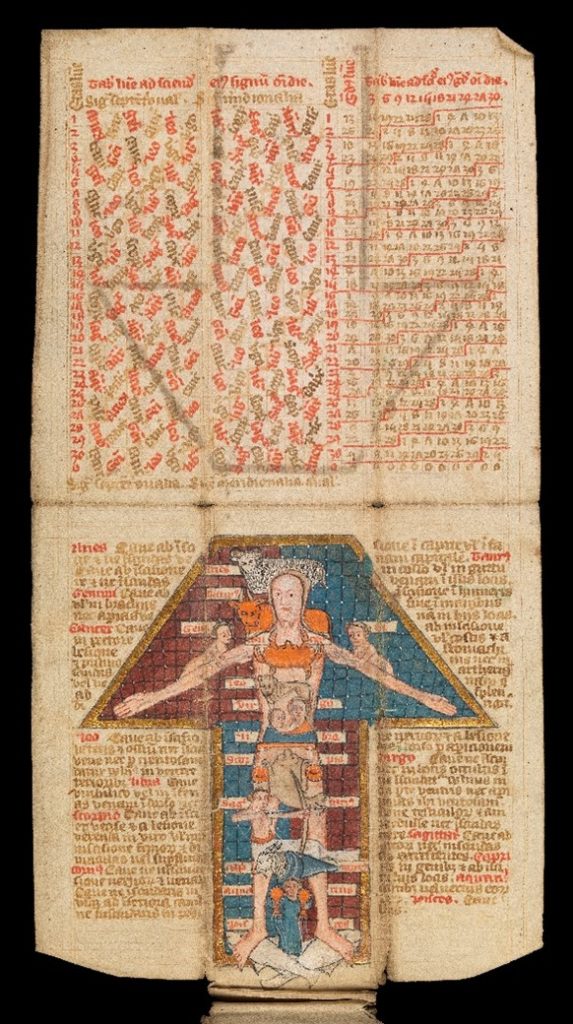

The earliest form of almanac we know of are the Babylonian Almanacs, cuneiform clay tablets made in C7 BC, which record astronomical observations, political events, commodity prices and weather reports, as well as making astrological predictions. The first hand written almanacs were made in the C12, designed to be carried by the owner, attached to his/her belt, and the first printed almanac was published at Mainz by Gutenberg in 1457.

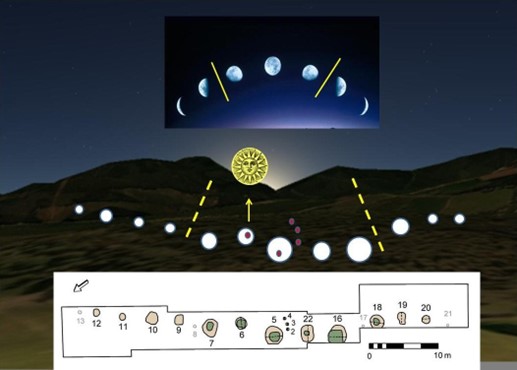

Some of the earliest calendars are believed to have been used by agricultural societies in order to plan activities such as sowing and harvesting, and finding their place in space and time, these people would naturally read the night sky to gain a greater understanding of future events. They would have linked momentous events in their lives to unusual celestial occurrences.

Notable early calendars include Warrren Field in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Believed to be the earliest surviving calendar at 10 – 8,000 years old, it was discovered by RCAHMS in 1976 using aerial photography, and consists of a series of 12 pits which would have originally held posts. Research suggests it was used by a mesolithic hunter/gatherer society, which was surprising, given the association with calendars and agriculture. The structure would have been used to track seasonal patterns associated with various food sources – the migration of various animals most importantly.

relationship to position of the Sun and phases of the Moon

These early calendars were shaping human behaviours, not only practical and functional, but also social and personal. For example, a woman could use the lunar cycle to track her fertility and gatherings could be organised between distant settlements.

As societies grew and became more complex, and people’s roles within society were increasingly defined, the astronomer/astrologer emerged. They would have been religious leaders, philosophers, mathematicians, and would have occupied a powerful place within society, having the skills to predict future events. Some became advisers to royalty and civil leaders, and they would be well placed to influence political events and religious movements.

These cultural changes would have altered people’s sense of place and time. Protestantism advocated a personal/direct relationship with God through textual study and personal prayer, God being omnipresent, time and location would be chosen with significance to the individual.

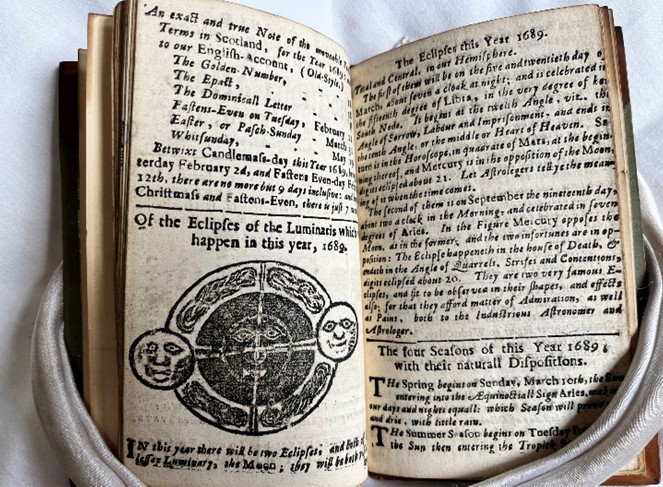

The Copernican/Galilean/Newtonian theories of heliocentrism were somewhat controversial in the late C17, generally unaccepted by the populace, but by the 1680, judicial astrology was being phased out of University curriculums in Europe. Up until this time, astronomy and astrology were taught alongside each other, and astrologers were academically respected. Astrology could not share a curriculum with heliocentric ideas as it required an assumption of a geocentric universe, with the sun traveling around the earth, and passing through various constellations.

By the time Jonathan Swift wrote under the pseudonym of Isaac Bickerstaff in order to invalidate John Partridges ‘Merlinus Liberatus’ in 1708, the art of astrology was becoming quite unfashionable among the educated classes.

Time itself had begun to be experienced differently in the Early Modern period – the introduction of clocks in wealthier houses and public spaces in many towns divided the days into hours, rather than relying on observations of the sky. Throughout this period people may have felt uncertain as to their position within the physical and temporal world, and almanacs would have rooted their owners firmly in space and time, regardless of religious and scientific leanings.

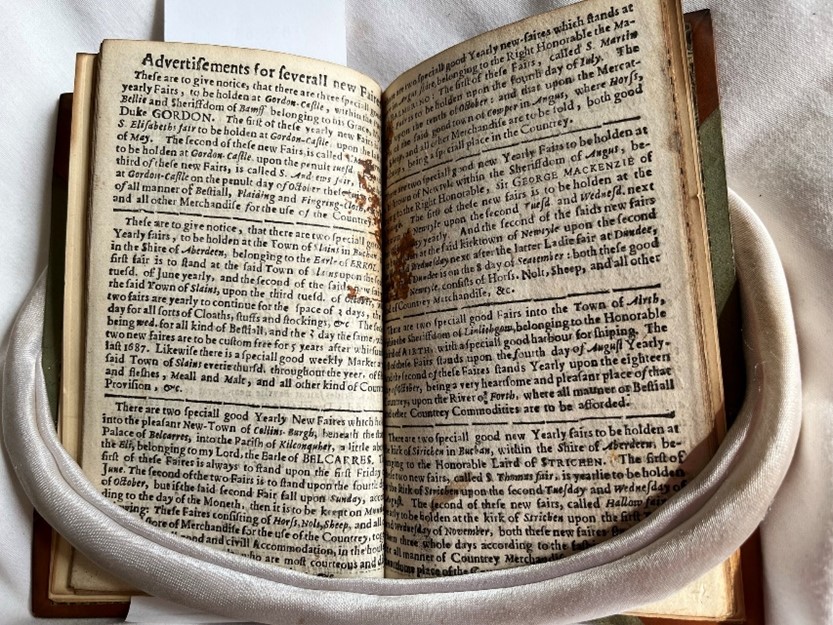

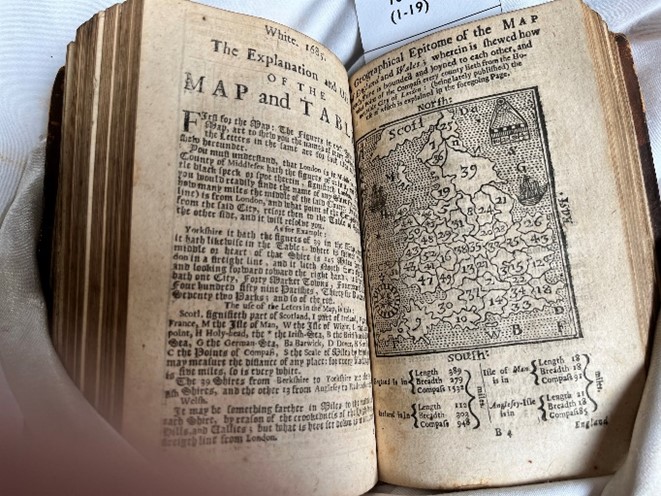

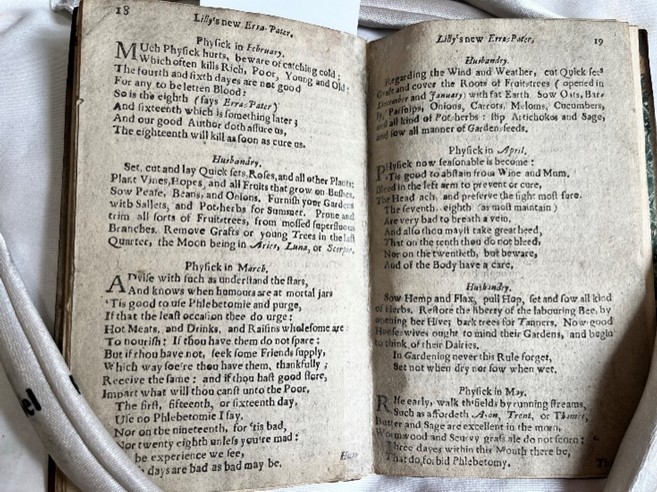

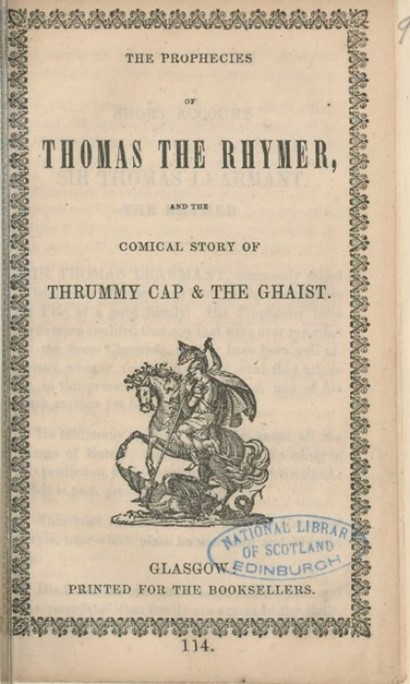

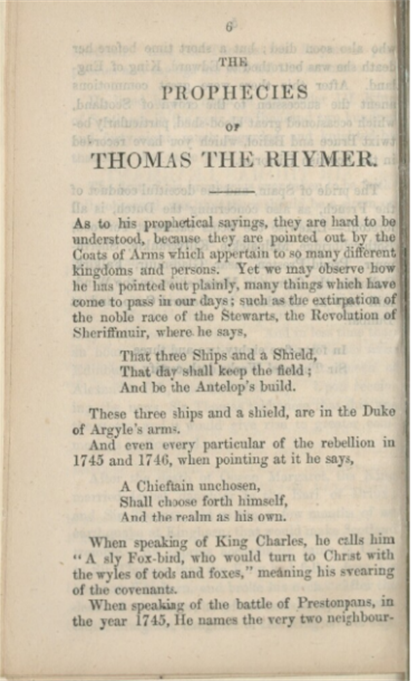

They were published for specific locations – astrology charts made for the South of England would not hold true for Scotland, and they organised one’s entire year into days and months with corresponding positions of celestial bodies. It would be possible, using an almanac, to plan the year with foreknowledge of astrological influences and thereby gain an advantage over one’s neighbours. Almanacs varied in style, but most made predictions or ‘prognostications’ for the following year, which would be closely watched or read for entertainment. Some included entertaining stories, helpful advice, folk remedies for ailments. This was the appeal of the almanac and we can see why they circulated in such huge numbers at the time.

With religious and political unrest dominating people’s lives in the C17, almanac writers and printers occupied a uniquely influential position, and it has been argued that these publications represent the beginnings of the popular press. Levels of censorship vary across the history of almanac publication – it was often evaded through the use of religious language, latin (only understood by educated people), and deliberate vagueness when making prophetic statements. in 1603 the Stationer’s Company were granted a Royal patent to form a joint stock company which would have the right to publish almanacs in perpetuity, with censorship not highly prioritised as these were their highest earning publications. This monopoly continued until the 1770s when the agreement was overturned. During the Civil War censorship of the cheap press virtually ceased, being a low priority, and between 1640-1660 England saw an explosion of almanacs catering to all political and religious tastes.

Post Restoration, the popularity of almanacs reached their historic peak. Following the Scientific Revolution and the decline in astrology’s fashionability, almanacs were marketed as ‘satirical ( being read for entertainment, but still having a prophetic element) and as registers/pocket companions/diaries aimed at wealthier/educated people. This pattern has held ever since in England and Scotland, with an expansion of publications for the two markets from the mid C19 onwards.

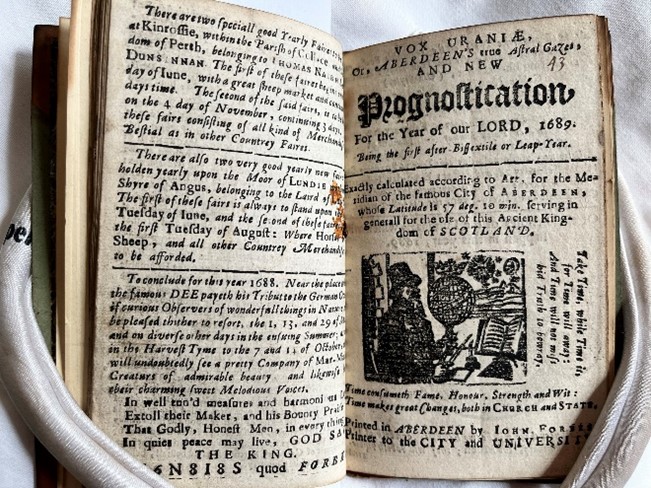

Scottish almanacs were traditionally more restrained in terms of the ‘prognostications’ contained within. The earlier publications would have a calendar, a section of ‘natural astrology’, and dates of fairs etc, but no prognostications/prophecies. This ‘editorial style‘ is in keeping with the cultural stereotype of Scottish publishing, with its emphasis on the scientific/rational. The reason for the omission of prophetic content, argues Joseph Robertson in ‘Sketch of the History of Scottish Almanacs’ is that the earliest Scottish almanacs forerunners were not prognostications from England and Europe, but the Kalendars prefixed to Bibles, psalm books, and other ecclesiastical texts.

Printing permission in Scotland in the C17 was controlled by the King and the Privy Council at national level, while town councils (printing burghs) licensed local publications, such as almanacs. The church advised the printing burghs, removing any judicial astrology/prophecies from the pages. Natural astrology was not incompatible with religion at this time – people read the heavens, as they’d always done in order to interpret God’s will. The biblical verse ‘”For everything there is a season..” (Ecclesiastes 3:1-22) is very ‘almanacal’ in spirit, for example.

The earliest almanac to be printed and sold widely was the Aberdeen Almanac, originally printed by Edward Raban in 1623, and by the 1660s almanacs were being printed in runs of 50,000. The late 1600s saw an explosion of the cheap print market, with divination etc content being available within chapbooks and pamphlets. This would suggest that some forms of cheap print were less heavily censored than others, and this is a pattern which continues into the C19, although by the late 1700s the market had diversified, with the educated classes buying almanacs, while the rest of the populace bought the cheaper and more sensational chapbooks.

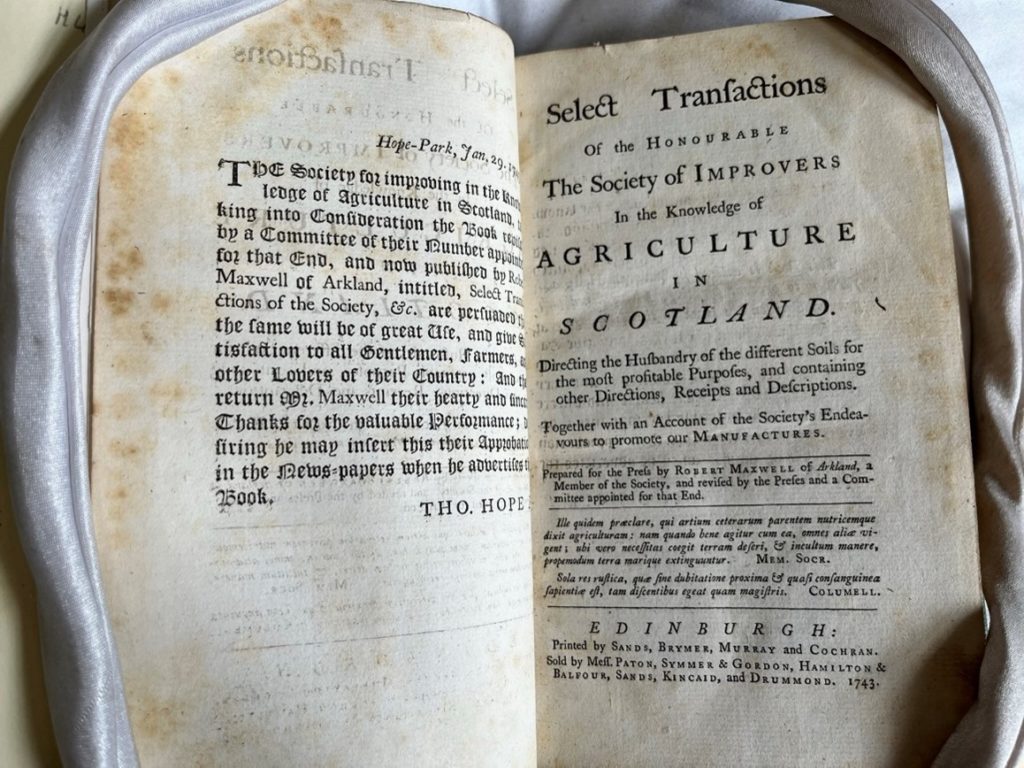

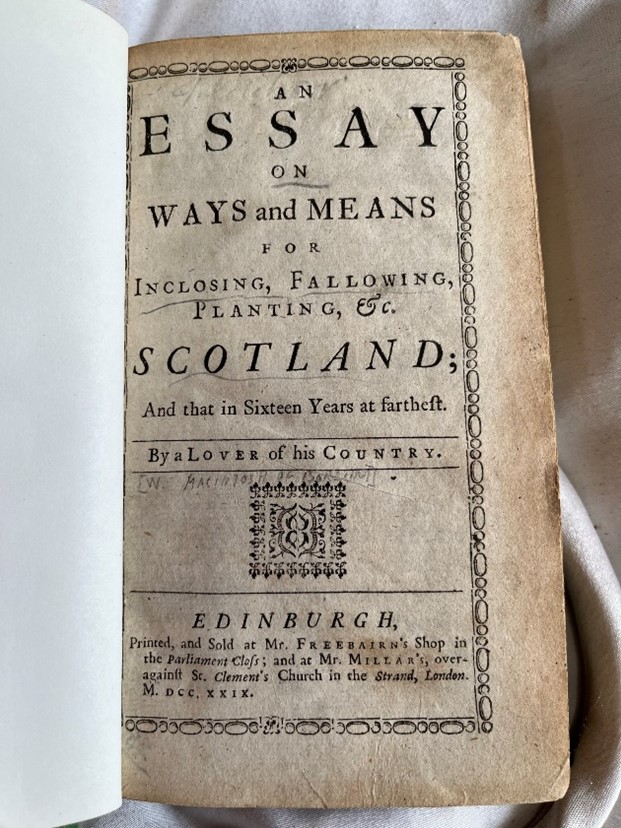

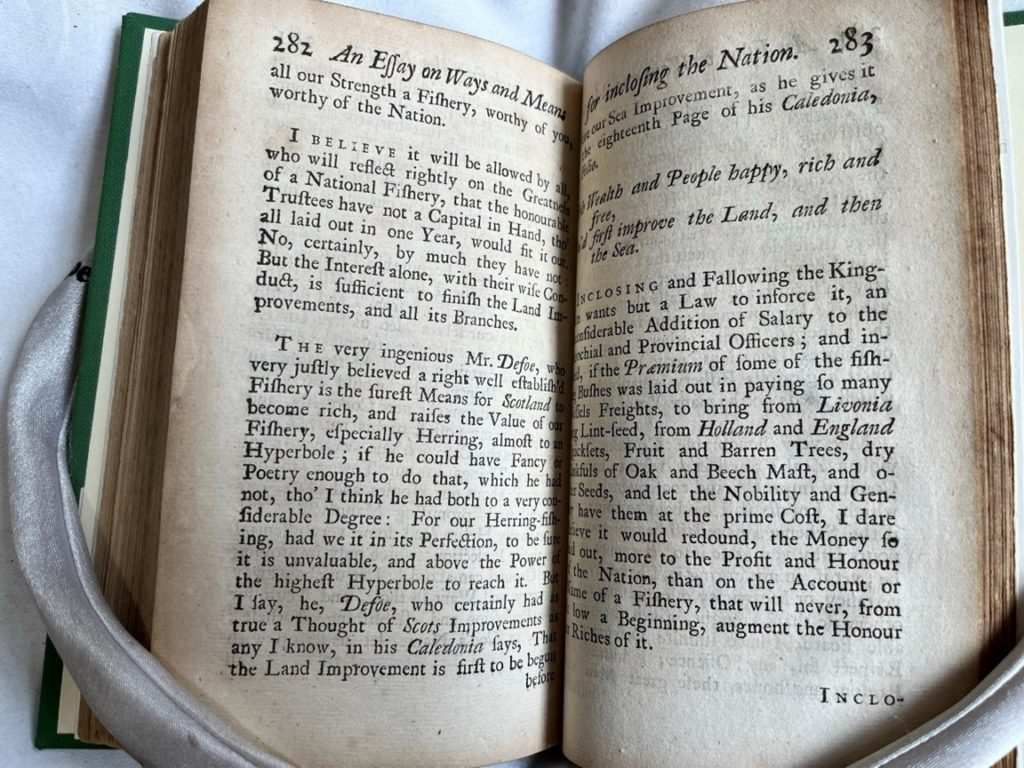

By the mid C18 the Scottish Agricultural Revolution had transformed farming practices with almost every member of the land owning classes engaged with ‘improvement’, and many would use an almanac to plan their agricultural activities. The agricultural connection, linking these modern almanacs with the earliest timekeeping devices gives a pleasing sense of continuity.

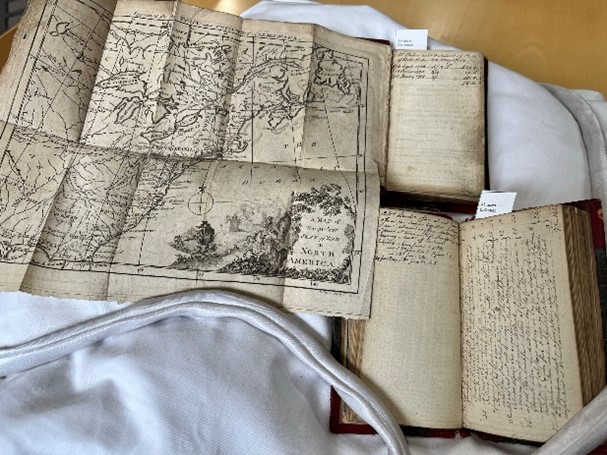

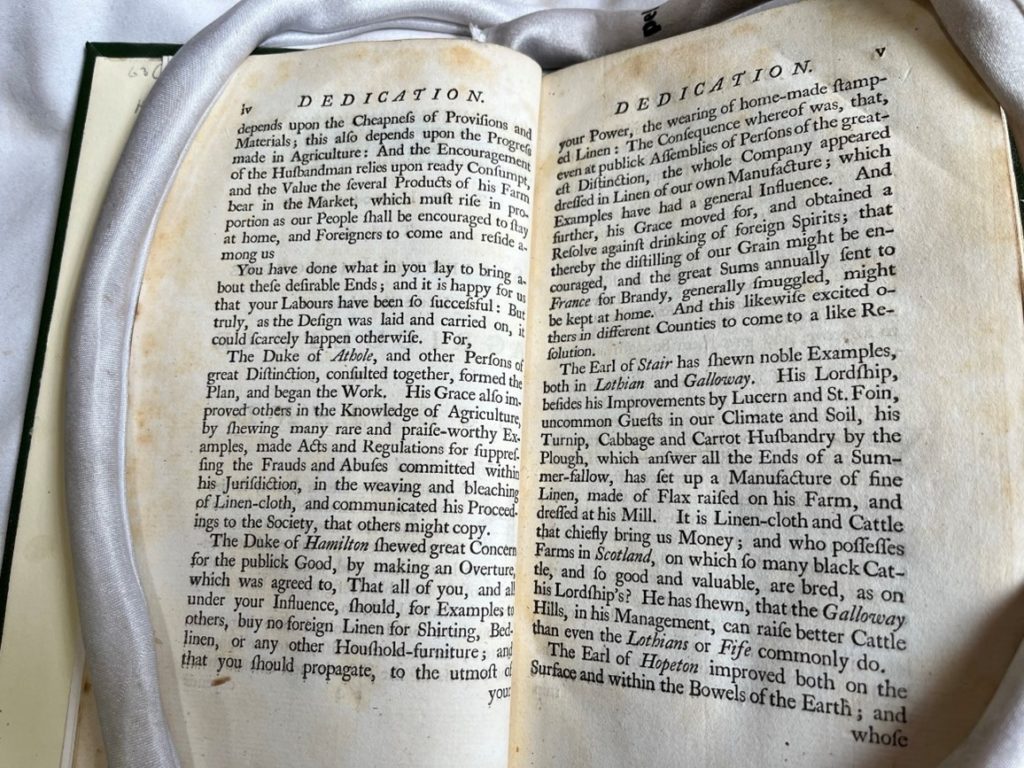

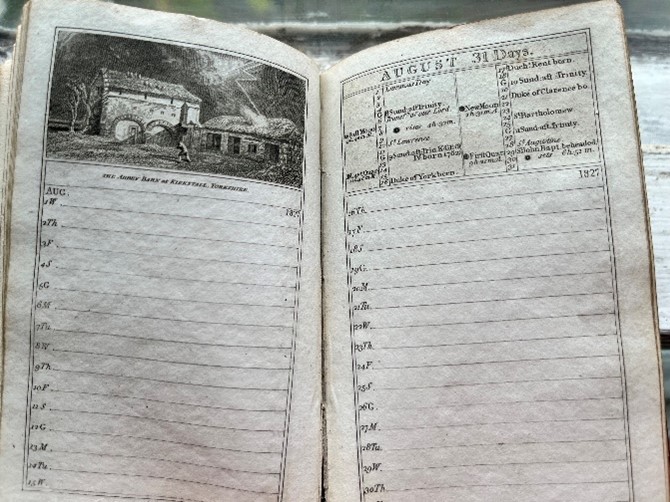

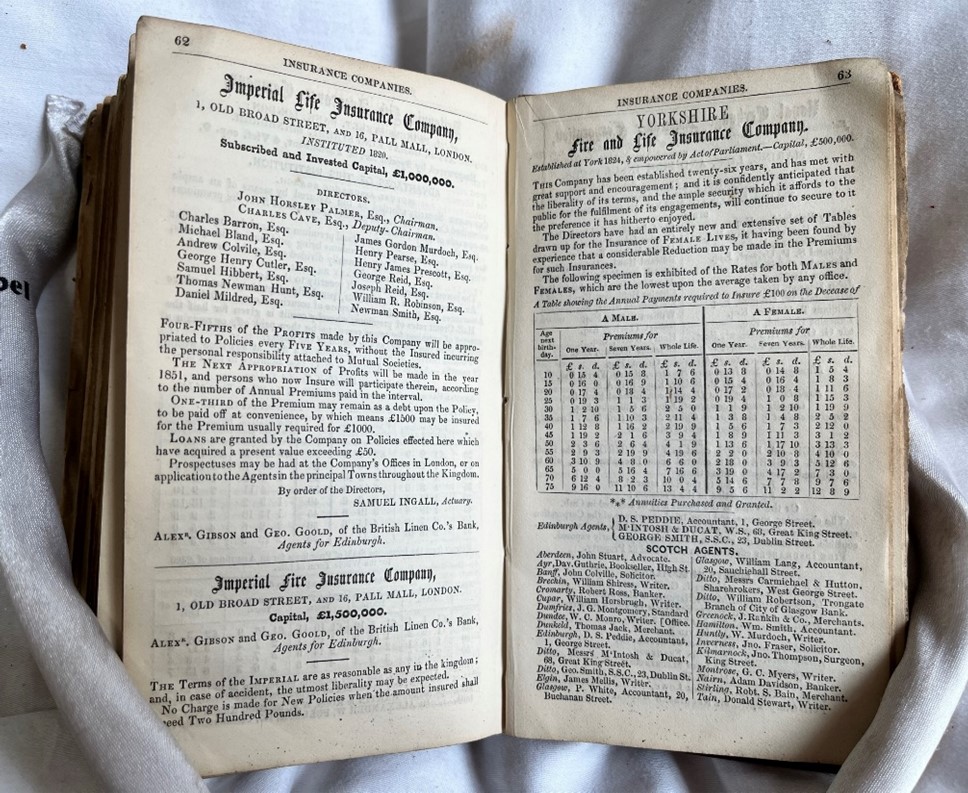

The post Union almanacs were far more comprehensive than their C17/early C18 counterparts, aimed at the professional classes, they contain many lists of Royal, political, legal and military people, travel information, useful facts and figures, and possibly a fold-out map. Also, crucially, they contained blank pages intended to allow the owner to make their own notes. The assumption that their customers were literate, and the way in which they would use these books is borne out by the survival of many almanacs from this period in which owners have written accounting and farming notes, birth dates of their children, and even brief diaries.

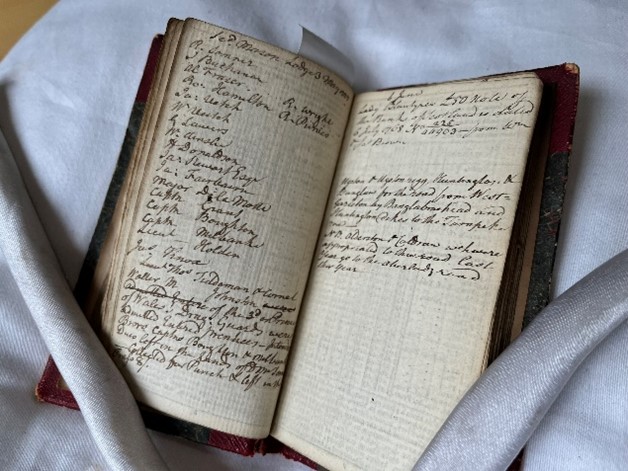

Many of the almanacs in the collection of the WS Society have these handwritten notes, which have helped us to identify some of the owners. All are from the legal profession, and one particular group of volumes belonged to William Law of Elvingston (1714-1806) Advocate and Sheriff of Haddingtonshire. He used his almanacs for accounting, notes on legal cases, farming notes, and several pages of a diary detailing his travels in East Lothian and Fife. William had a successful estate near Haddington, where he made reforms in farmer’s leases with respect to dung ownership. He mentions many names of local significance such as Lord Cockburn, Lady Blantyre, Mr Dods (seed merchant), and fascinatingly, a list of members of the ‘Scd Mason Lodge’.

These almanacs represent a real cultural expression of the Scottish Agricultural Revolution in East Lothian (the location of many of the founders of the movement) and continue the tradition of rooting the user in place and time – although the astrological information is minimal, the calendar maintains its primary position within the book, and the owner is socially positioned within the many lists of names and societies. Each almanac was still published for a particular location with corresponding local directories, but reinvented for a modern owner, and they would have fulfilled the same purpose of providing a reassuring presence, kept in the pocket or bag at all times.

The market for these books remained buoyant throughout the C18 and was jealously guarded by the individual publishers – the principal threat was from forged and fraudulent publications – the Aberdeen Almanack suffered several attempts by unscrupulous printers. Almanacs would have been compiled in secrecy for this reason, and publishing day was carefully planned – the books handed over to a network of ‘chapmen’, responsible for distributing them as quickly as possible.

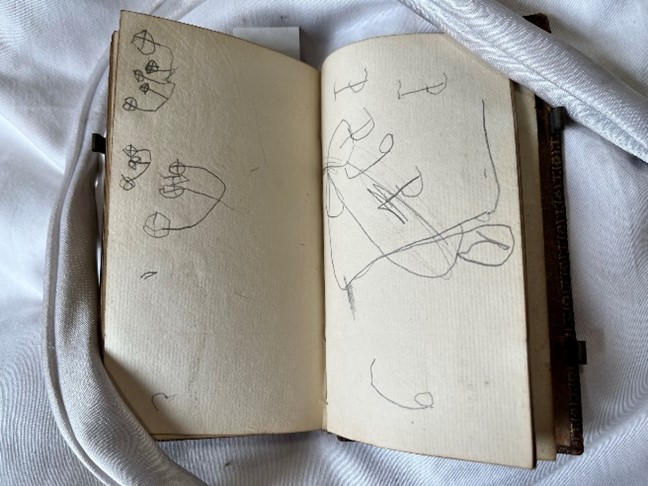

The other threat to the almanac’s sales was the pocket diary. Almanacs had been used to record people’s ‘life writing’ since the mid C17 when they became affordable to the general populace, and the inclusion of blank pages may have been inspired by the practice of tipping in pieces of scrap paper in order to make notes. George Washington famously sewed extra pages into his Virginia Almanack in order to make a daily journal alongside the astrological information.

Publishers were including these blank pages in many almanacs for the latter half of the C18, revealing a market for journals and planners, which were exempt from Stamp Duty. By excluding the word ‘almanac’ from the title, these publishers were able to make a good profit from the sales, and by the early C19 the market had diversified to include all sorts of pocket books and diaries.

The pocket diary was a direct descendant of the astrological almanac, reimagined for the new mercantile classes and gentry. A golden age of diary writing lay ahead as well-heeled young people set off on their Grand Tours of Europe, with the obligatory journal written each night.

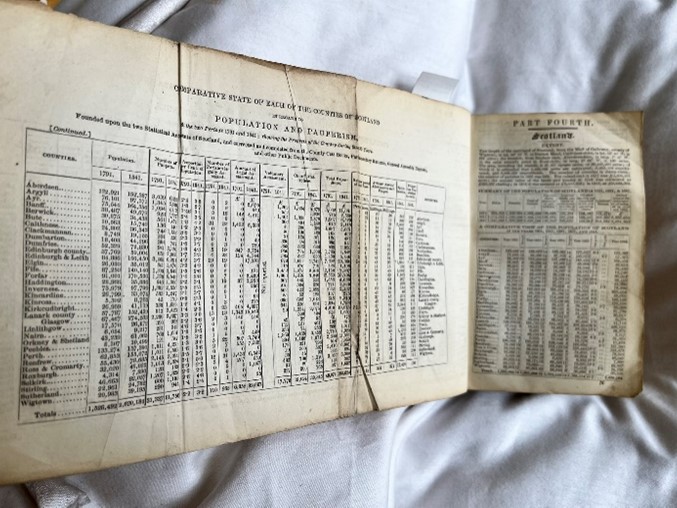

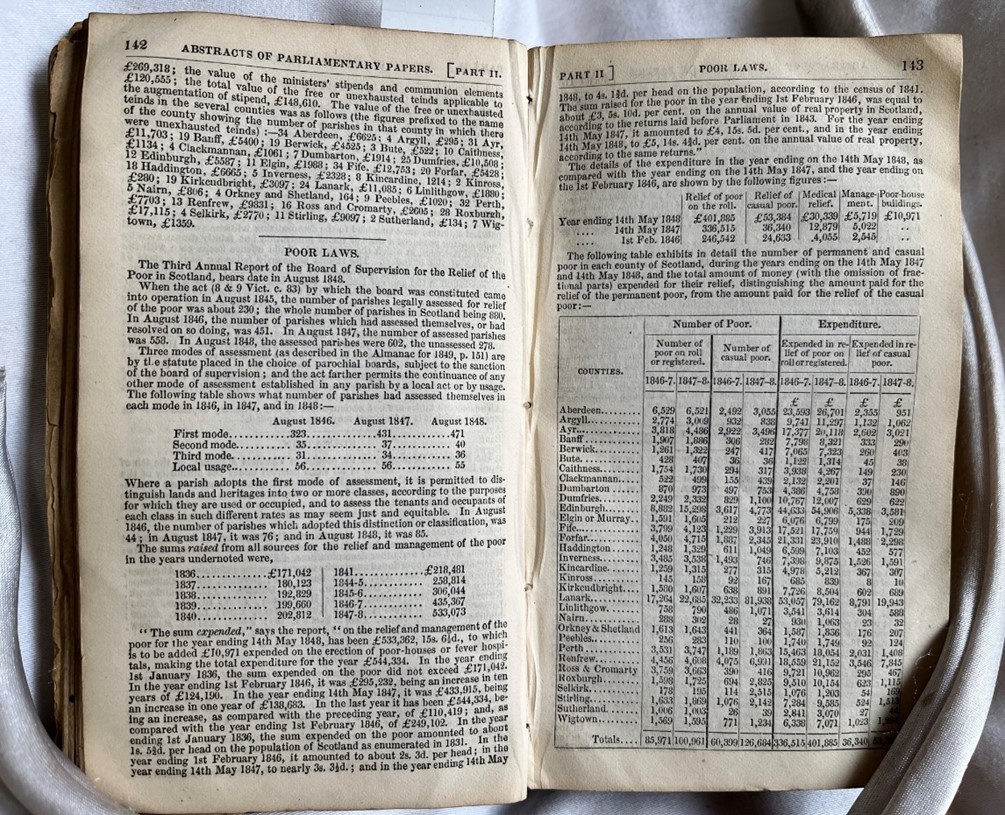

John Sinclair of Ulbster undertook his Statistical Account of Scotland after a visit to Europe in 1786 during which he researched various forms of agricultural improvement. His commitment towards improving his nation’s wealth and happiness inspired him to undertake the largest statistical survey in Scotland to date. Questionnaires were sent to over 900 parish ministers and the results compiled, producing a work which had a significant impact on Scottish agriculture and industry.

Another change seen in this collection of almanacs is the disappearance of the blank ‘diary’ pages, indicating a change in the way they were used. The register style almanacs, which were growing in size with every passing year, had increasingly ornamental bindings and were intended for office use, while the pocket diaries continued to be kept on the person.

By this time the market had fully diverged, with the general populace still enjoying the traditional almanacs, some of which contained humour, wild prophecies, folk remedies and stories to divert throughout the year.

This example from Cassells’s Family Magazine in 1886 may or may not be true, but certainly gives an insight into the popular opinion of traditional almanacs and their readers at the time.

MORE HUMOUR IN ARCADIE.

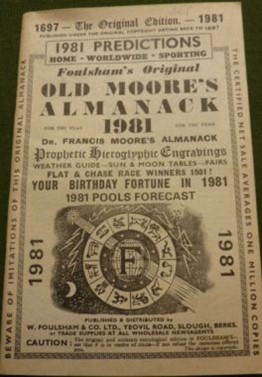

The almanac referred to here is most likely Old Moore’s Almanac or something very similar. Old Moore’s was traditionally the best selling almanac, at least in England, originally printed in London in 1697. It remained almost unchanged in style into the 1980s and has only relatively recently been given a ‘modern’ look. It is still read by those looking for prophecies, entertainment, and of course continuity and tradition.

A skilled country mechanic, a man of distinct pretensions to ability, lost his situation after fifteen years of approved service. He sought another, but at first unsuccessfully. Trade was depressed, and the outlook sombre. An opening offered in a somewhat novel quarter. The inquiry was made if he could commence work on the Monday succeeding his engagement. He hesitated, and lugubriously demurred.

“ I will come on the Tuesday, without fail,” he said.

“ Why not on the previous day ? ” curiously asked the employer.

“ It’s’a bad one, sir.”

“A bad one ! How ? I don’t understand.”

“By the almanac, sir. I wouldn’t marry on that day if I were ever so deeply smitten by Cupid’s arrow, as they call it on the valentines, and if it were a choice between then and never; and I won’t start at a new job on Monday next for any master in the country. Sorry to disoblige, sir.”

Remonstrance and ridicule were alike vain. “ No, no ; I mayn’t be able to explain it—there’s a heap o’ things in the world that we can’t tell just the why and the wherefore of—but I’ve proved it, and that’s better than explaining it,” he cried ; “ in fact, there’s a proof here in this little bit of business. My almanac told me I was to have changes this year. I looked all round, but couldn’t so much as guess where they were to come from. But you see that after all the almanac was right ; and I’ve noticed it scores of times.”

This same artisan stood sponsor on another occasion for a statement so curious as to be worth reproducing, as a specimen of the humours not simply of rural, but of technical superstition also. He was descanting on various occult influences of the heavenly bodies—a favourite topic with a congenial audience.

“ The moon’s power is very remarkable,” he said ; “ as is well known and admitted, it rules the tides. And it likewise makes a wonderful difference to timber. You may hardly credit this, but it’s a matter of experience again. Timber felled when the moon is waxing planes or cuts up nigh as easy again as the very same sort, and age, and growth of timber felled when the moon is on the wane. It’s queer, but true.”

Given the multitude of uses to which almanacs have been put in their popular 400 year history, it is difficult to identify their place in contemporary life. Many of their functions are now fulfilled by electronic devices and purpose built software. Predicting the future will never lose its popularity, and despite the many scientific methods of forecasting, genuine excitement is often reserved for individuals who seem to be ‘gifted’ in this way.

The WS Society’s collection of almanacs has now been catalogued, conserved, and is available for research. They are in remarkably good condition considering many of them were carried in pockets and bags for a year, and the close physical connection with their owners gives them a very special quality normally only found in Bibles and manuscripts.